(完整word版)约翰.卫斯理英文讲道第5篇

- 格式:docx

- 大小:21.40 KB

- 文档页数:11

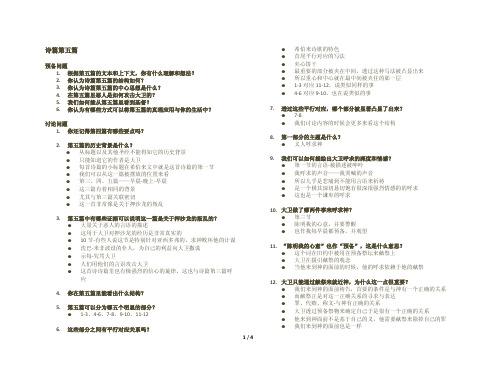

John WesleySERMON 65[text of the 1872 edition]THE DUTY OF REPROVING OUR NEIGHBOUR"Thou shalt not hate thy brother in thy heart: thou shalt in any wise rebuke thy neighbour, and not suffer sin upon him." Lev. 19:17.A great part of the book of Exodus, and almost the whole of the book of Leviticus, relate to the ritual or ceremonial law of Moses; which was peculiarly given to the children of Israel, but was such "a yoke," says the apostle Peter, "as neither our fathers nor we were able to bear." We are, therefore, delivered from it: And this is one branch of "the liberty wherewith Christ hath made us free." Yet it is easy to observe, that many excellent moral precepts are interspersed among these ceremonial laws. Several of them we find in this very chapter: Such as, "Thou shalt not gather every grape of thy vineyard: Thou shalt leave them for the poor and stranger. I am the Lord your God." (Lev. 19:10.) Ye shall not steal, neither lie one to another. (Lev. 19:11.) "Thou shalt not defraud thy neighbour, neither rob him: The wages of him that is hired shall not abide with thee till the morning." (Lev. 19:13.) "Thou shalt not curse the deaf, nor put a stumbling-block before the blind; but shalt fear thy God: I am the Lord." (Lev. 19:14.) As if he had said, I am he whose eyes are over all the earth, and whose ears are open to their cry. "Ye shall do no unrighteousness in judgment: Thou shalt not respect the person of the poor," which compassionate men may be tempted to do; "nor honour the person of the mighty," to which there are a thousand temptations. (Lev. 19:15.) "Thou shalt not go up and down as a tale-bearer among thy people:" (Lev. 19:16:) Although this is a sin which human laws have never yet been able to prevent. Then follows, "Thou shalt not hate thy brother in thy heart: Thou shalt in anywise rebuke thy neighbour, and not suffer sin upon him." [Lev. 19:17]In order to understand this important direction aright, and to apply it profitably to our own souls, let us consider,I. What it is that we are to rebuke or reprove? What is the thing that is here enjoined?II. Who are they whom we are commanded to reprove? And,III. How are we to reprove them?I. 1. Let us consider, First, What is the duty that is here enjoined? What is it we are to rebuke or reprove? And what is it to reprove? What is it to reprove? To tell anyone of his faults; as clearly appears from the following words: "Thou shalt not suffer sin upon him." Sin is therefore the thing we are called to reprove, or rather him that commits sin. We are to do all that in us lies to convince him of his fault, and lead him into the right way.2. Love indeed requires us to warn him, not only of sin, (although of this chiefly,) but likewise of any error which, if it were persisted in, would naturally lead to sin. If we do not "hate him in our heart," if we love our neighbour as ourselves, this will be our constant endeavour; to warn him of every evil way, and of every mistake which tends to evil.3. But if we desire not to lose our labour, we should rarely reprove anyone for anything that is of a disputable nature, that will bear much to be said on both sides. A thing may possibly appear evil to me; therefore I scruple the doing of it; and if I were to do it while that scruple remains, I should be a sinner before God. But another is not to be judged by my conscience: To his own master he standeth or falleth. Therefore I would not reprove him, but for what is clearly and undeniably evil. Such, for instance, is profane cursing and swearing; which even those who practise it most will not often venture to defend, if one mildly expostulates with them. Such is drunkenness, which even a habitual drunkard will condemn when he is sober. And such, in the account of the generality of people, is the profaning of the Lord's day. And if any which are guilty of these sins for a while attempt to defend them, very few will persist to do it, if you look them steadily in the face, and appeal to their own conscience in the sight of God.II. 1. Let us, in the Second place, consider, Who are those that we are called to reprove? It is the more needful to consider this, because it is affirmed by many serious persons, that there are some sinners whom the Scripture itself forbids us to reprove. This sense has been put on that solemn caution of our Lord, in his Sermon on the Mount: "Cast not your pearls before swine, lest they trample them under foot, and turn again and rend you." But the plain meaning of these words is, Do not offer the pearls, the sublime doctrines or mysteries of the Gospel, to those whom you know to be brutish men, immersed in sins, and having no fear of God before their eyes. This would expose those precious jewels to contempt, and yourselves to injurious treatment. But even those whom we know to be,in our Lord's sense, dogs and swine, if we saw them do, or heard them speak, what they themselves know to be evil, we ought in any wise to reprove them; else we "hate our brother in our heart."2. The persons intended by "our neighbour" are, every child of man, everyone that breathes the vital air, all that have souls to be saved. And if we refrain from performing this office of love to any, because they are sinners above other men, they may persist in their iniquity, but their blood will God require at our hands.3. How striking is Mr. Baxter's reflection on this head, in his "Saints' Everlasting Rest! "Suppose thou wert to meet one in the lower world, to whom thou hadst denied this of fice of love, when ye were both together under the sun; what answer couldst thou make to his upbraiding? `At such a time and place, while we were under the sun, God delivered me into thy hands. I then did not know the way of salvation, but was seeking death in the error of my life; and therein thou sufferedst me to remain, without once endeavouring to awake me out of sleep! Hadst thou imparted to me thy knowledge, and warned me to flee from the wrath to come, neither I nor thou need ever have come into this place of torment.'"4. Every one, therefore, that has a soul to be saved, is entitled to this good office from thee. Yet this does not imply, that it is to be done in the same degree to everyone. It cannot be denied, that there are some to whom it is particularly due. Such, in the first place, are our parents, if we have any that stand in need of it; unless we should place our consorts and our children on an equal footing with them. Next to these we may rank our brothers and sisters, and afterwards our relations, as they are allied to us in a nearer or more distant manner, either by blood or by marriage. Immediately after these are our servants, whether bound to us for a term of years or any shorter term. Lastly, such in their several degrees are our countrymen, our fellow-citizens, and the members of the same society, whether civil or religious: The latter have a particular claim to our service; seeing these societies are formed with that very design, to watch over each other for this very end, that we may not suffer sin upon our brother. If we neglect to reprove any of these, when a fair opportunity offers, we are undoubtedly to be ranked among those that "hate their brother in their heart." And how severe is the sentence of the Apostle against those who fall under this condemnation! "He that hateth his brother," though it does not break out into words or actions, "is a murderer:" And ye know," continues the Apostle, "that no murderer hath eternal life abiding in him." He hath not that seed planted in his soul, which groweth up unto everlasting life: In other words, he is in such a state, that if he dies therein, he cannot see life. It plainly follows,that to neglect this is no small thing, but eminently endangers our final salvation.III. We have seen what is meant by reproving our brother, and who those are that we should reprove. But the principal thing remains to be considered. How, in what manner, are we to reprove them?1. It must be allowed, that there is a considerable difficulty in performing this in a right manner: Although, at the same time, it is far less difficult to some than it is to others. Some there are who are particularly qualified for it, whether by nature, or practice, or grace. They are not encumbered either with evil shame, or that sore burden, the fear of man: They are both ready to undertake this labour of love, and skilful in performing it. To these, therefore, it is little or no cross; nay, they have a kind of relish for it, and a satisfaction therein, over and above that which arises from a consciousness of having done their duty. But be it a cross to us, greater or less, we know that hereunto we are called. And be the difficulty ever so great to us, we know in whom we have trusted; and that he will surely fulfil his word, "As thy day, so shall thy strength be."2. In what manner, then, shall we reprove our brother, in order that our reproof may be most effectual? Let us first of all take care that whatever we do may be done in "the spirit of love;" in the spirit of tender good-will to our neighbour; as for one who is the son of our common Father, and one for whom Christ died, that he might be a partaker of salvation. Then, by the grace of God, love will beget love. The affection of the speaker will spread to the heart of the hearer; and you will find, in due time, that your labour hath not been in vain in the Lord.3. Meantime the greatest care must be taken that you speak in the spirit of humility. Beware that you do not think of yourself more highly than you ought to think. If you think too highly of yourself, you can scarce avoid despising your brother. And if you show, or even feel, the least contempt of those whom you reprove, it will blast your whole work, and occasion you to lose all you labour. In order to prevent the very appearance of pride, it will be often needful to be explicit on the head; to disclaim all preferring yourself before him; and at the very time you reprove that which is evil, to own and bless God for that which is good in him.4. Great care must be taken, in the Third place, to speak in the spirit of meekness,as well as lowliness. The Apostle assures us that "the wrath of men worketh not the righteousness of God." Anger, though it be adorned with the name of zeal, begets anger; not love or holiness. We shouldtherefore avoid, with all possible care, the very appearance of it. Let there be no trace of it, either in the eyes, the gesture, or the tone of voice; but let all of these concur in manifesting a loving, humble, and dispassionate spirit.5. But all this time, see that you do not trust in yourself. Put no confidence in your own wisdom, or address, or abilities of any kind. For the success of all you speak or do, trust not in yourself, but in the great Author of every good and perfect gift. Therefore, while you are speaking, continually lift up your heart to him that worketh all in all. And whatsoever is spoken in the spirit of prayer,will not fall to the ground.6. So much for the spirit wherewith you should speak when you reprove your neighbour. I now proceed to the outward manner. It has been frequently found that the prefacing a reproof with a frank profession of good-will has caused what was spoken to sink deep into the heart. This will generally have a far better effect, than that grand fashionable engine, -- flattery, by means of which the men of the world have often done surprising things. But the very same things, yea, far greater, have much oftener been effected by a plain and artless declaration of disinterested love. When you feel God has kindled this flame in your heart, hide it not; give it full vent! It will pierce like lightning. The stout, the hard-hearted, will melt before you, and know that God is with you of a truth.7. Although it is certain that the main point in reproving is, to do it with a right spirit, yet it must also be allowed, there are several little circumstances with regard to the outward manner, which are by no means without their use, and therefore are not to be despised. One of these is, whenever you reprove, do it with great seriousness;so that as you really are in earnest, you may likewise appear so to be. A ludicrous reproof makes little impression, and is soon forgot; besides, that many times is taken ill, as if you ridiculed the person you reprove. And indeed those who are not accustomed to make jests, do not take it well to be jested upon. One means of giving a serious air to what you speak, is, as often as may be, to use the very words of Scripture. Frequently we find the word of God, even in a private conversation, has a peculiar energy; and the sinner, when he expects it least, feels it "sharper than a two-edged sword."8. Yet there are some exceptions to this general rule of reproving seriously. There are some exempt cases, wherein, as a good judge of human nature observes,_Ridiculum acri fortius_ --a little well-placed raillery will pierce deeper than solid argument. But this has place chiefly, when we have to do with those who are strangersto religion. And when we condescend to give a ludicrous reproof to a person of this character, it seems we are authorized so to do, by that advice of Solomon, "Answer a fool according to his folly, lest he be wise in his own eyes."9. The manner of the reproof may, in other respects too, be varied according to the occasion. Sometimes you may find it proper to use many words, to express your sense at large. At other times you may judge it more expedient to use few words, perhaps a single sentence; and at others, it may be advisable to use no words at all, but a gesture, a sigh, or a look, particularly when the person you would reprove is greatly your superior. And frequently, this silent kind of reproof will be attended by the power of God, and consequently, have a far better effect than a long and laboured discourse.10. Once more: Remember the remark of Solomon, "A word spoken in season, how good is it!" It is true, if you are providentially called to reprove anyone whom you are not likely to see any more, you are to snatch the present opportunity, and to speak "in season" or "out of season;" but with them whom you have frequent opportunities of seeing, you may wait for a fair occasion. Here the advice of the poet has place. You may speak_Si validus, si laetus erit, si denique poscet:_ When he is in a good humour, or when he asks it you. Here you may catch the_Mollia tempora fandi,_ --time when his mind is in a soft, mild frame: And then God will both teach you how to speak, and give a blessing to what is spoken.11. But here let me guard you against one mistake. It passes for an indisputable maxim, "Never attempt to reprove a man when he is intoxicated with drink." Reproof, it is said, is then thrown away, and can have no good effect. I dare not say so. I have seen not a few clear instances of the contrary. Take one: Many years ago, passing by a man in Moorfields, who was so drunk he could hardly stand, I put a paper into his hand. He looked at it, and said, "A Word -- A Word to a Drunkard, -- that is me, -- Sir, Sir! I am wrong, -- I know I am wrong, -- pray let me talk a little with you." He held me by the hand a full half-hour: And I believe he got drunk no more.12. I beseech you, brethren, by the mercies of God, do not despise poor drunkards! Have compassion on them! Be instant with them in season and out of season! Let not shame, or fear of men prevent your pulling these brands out of the burning: Many of them are self-condemned:Nor do they not discern the evil plightThat they are in;but they despair; they have no hope of escaping out of it; and they sink into it still deeper, because none else has any hope for them! "Sinners of every other sort," said a venerable old Clergyman, "have I frequently known converted to God. But an habitual drunkard I have never known converted." But I have known five hundred, perhaps five thousand. Ho! Art thou one who readest these words? Then hear thou the words of the Lord!I have a message from God unto thee, O sinner! Thus saith the Lord, Cast not away thy hope. I have not forgotten thee. He that tells thee there is no help is a liar from the beginning. Look up! Behold the Lamb of God, who taketh away the sin of the world! This day is salvation come to thy soul: Only see that thou despise not him that speaketh! Just now he saith unto thee: "Son, be of good cheer! Thy sins are forgiven thee!"13. Lastly: You that are diligent in this labour of love, see that you be not discouraged, although after you have used your best endeavours, you should see no present fruit. You have need of patience, and then, "after ye have done the will of God" herein, the harvest will come. Never be "weary of well-doing; in due time ye shall reap, if ye faint not." Copy after Abraham, who "against hope, still believed in hope." "Cast thy bread upon the waters; for thou shalt find it after many days."14. I have now only a few words to add unto you, my brethren, who are vulgarly called "Methodists." I never heard or read of any considerable revival of religion which was not attended with a spirit of reproving.I believe it cannot be otherwise; for what is faith, unless it worketh by love? Thus it was in every part of England when the present revival of religion began about fifty years ago: All the subjects of that revival, -- all the Methodists, so called, in every place, were reprovers of outward sin. And, indeed, so are all that "being justified by faith, have peace with God through Jesus Christ." Such they are at first; and if they use that precious gift, it will never be taken away. Come, brethren, in the name of God, let us begin again! Rich or poor, let us all arise as one man; and in any wise let every man "rebuke his neighbour, and not suffer sin upon him!" Then shall all Great Britain and Ireland know that we do not "go a warfare at our own cost:" Yea, "God shall bless us, and all the ends of the world shall fear him." Manchester, July 28, 1787[Edited by Dave Giles, student at Northwest Nazarene College (Nampa, ID), with corrections by George Lyons for the Wesley Center for Applied Theology.]。

English Book 5 Lesson 1 救赎----兰斯顿.休斯在我快13岁那年,我的灵魂得到了拯救,然而并不是真正意义上的救赎。

事情是这样的。

那时我的阿姨里德所在的教堂正在举行一场盛大的宗教复兴晚会。

数个星期以来每个夜晚,人们在那里讲道,唱诵,祈祷。

连一些罪孽深重的人都获得了耶稣的救赎,教堂的成员一下子增多了。

就在复兴晚会结束之前,他们为孩子们举行了一次特殊的集会——把小羊羔带回羊圈。

里德阿姨数日之前就开始和我提这件事。

那天晚上,我和其他还没有得到主宽恕的小忏悔者们被送去坐在教堂前排,那是为祷告的人安排的座椅。

我的阿姨告诉我说:“当你看到耶稣的时候,你看见一道光,然后感觉心里似乎有什么发生。

从此以后耶稣就进入了你的生命,他将与你同在。

你能够看见、听到、感受到他和你的灵魂融为一体。

”我相信里德阿姨说的,许多老人都这么说,似乎她们都应该知道。

尽管教堂里面拥挤而闷热,我依然静静地坐在那里,等待耶稣的到来。

布道师祷告,富有节奏,非常精彩。

呻吟、喊叫、寂寞的呼喊,还有地狱中令人恐怖的画面。

然后他唱了一首赞美诗。

诗中描述了99只羊都安逸的待在圈里,唯有一个被冷落在外的情形。

唱完后他说道:“难道你不来吗?不来到耶稣身旁吗?小羊羔们,难道你们不来吗?”他向坐在祷告席上的小忏悔者们打开了双臂,小女孩们开始哭了,她们中有一些很快跳了起来,跑了过去。

我们大多数仍然坐在那里。

许多长辈过来跪在我们的身边开始祷告。

老妇人的脸像煤炭一样黑,头上扎着辫子,老爷爷的手因长年的工作而粗糙皲裂。

他们吟唱着“点燃微弱的灯,让可怜的灵魂得到救赎”的诗歌。

整个教堂里到处都是祈祷者的歌声。

最后其他所有小忏悔者们都去了圣坛上,得到了救赎,除了一个男孩和依然静静地坐着等侯的我。

那个男孩是一个守夜人的儿子,名字叫威斯特里。

在我们的周围尽是祈祷的修女执事。

教堂里异常闷热,天色也越来越暗了。

最后威斯特里小声对我说:“去他妈的上帝。

我再也坐不住了,我们站起来吧,就可以得到救赎了。

John WesleySERMON 136[text from the 1872 edition]ON CORRUPTING THE WORD OF GODPreached about the year 1728"We are not as many, who corrupt the word of God: But as of sincerity, but as of God, in the sight of God speak we in Christ." 2 Cor. 2:17.[1.] Many have observed, that nothing conduces more to a Preacher's success with those that hear him, than a general good opinion of his sincerity. Nothing gives him a greater force of persuasion than this; nothing creates either a greater attention in the hearers or a greater disposition to improve. When they really believe he has no end in speaking, but what he fairly carries in view, and that he is willing that they should see all the steps he takes for the attainment of that end, -- it must give them a strong presumption, both that what he seeks is good, and the method in which he seeks it.[2.] But how to possess them with this belief is the question. How shall we bring them to take notice of our sincerity, if they do not advert to it of themselves? One good way, however common, is, frankly and openly to profess it. There is something in these professions, when they come from the heart, strongly insinuating into the hearts of others. The persons of any generosity that hear them find themselves almost forced to believe them; and even those who believe them not are obliged in prudence, not to let their incredulity appear, since it is a known rule, -- the honester any man is, the less apt is he to suspect another. The consequence whereof is plain: Whoever without proof, is suspicious of his neighbour's sincerity, gives a probable proof that he judges of his heart from the falseness of his own.[3.] Would not any man be tempted to suspect his integrity, who, without proof, suspected the want of it in another, that had fairly and openly professed the principles on which he acted? Surely none, but who himself corrupted the word of God, or wished that it were corrupted, could lightlysuspect either St. Paul of doing it, or any that after him should use his generous declaration: "We are not as many, who corrupt the word of God: But as of sincerity, but as of God, in the sight of God speak we in Christ."[4.] Not that the Apostle, any more than his followers in preaching the gospel, desires they should wholly rely on his words; for afterwards he appeals to his actions to confirm them. And those who in this can imitate him need not entreat men to believe their sincerity. If our works bear the stamp of it, as well as our words, both together will speak so loudly and plainly, every unprejudiced person must understand that we speak in Christ, as in sincerity, and that in so doing we consider we are in the sight of that God whose commission we bear.[5.] Those whom the Apostle accuses of the contrary practice, of corrupting the word of God, seem to have been Jews, who owning Jesus to be Christ, and his gospel to be divine, yet adulterated it, by intermingling with it the law of Moses, and their own traditions. And in doing this, their principal view was to make a gain of Christ; which, consequently, laid them under a necessity of concealing the end they proposed, as well as the means they used to obtain it. On the contrary, those who intend the good of mankind, are by no means concerned to hide their intentions. If the benefit we propose in speaking be to ourselves, it is often our interest to keep it private. If the benefit we propose be to others, it is always our interest to make it public; and it is the interest both of ourselves and others, to make public those marks of distinction whence may clearly be known who corrupt the word of God, and who preach it in sincerity.[I. 1.] The First and great mark of one who corrupts the word of God, is, introducing into it human mixtures; either the errors [heresies] of others, or the fancies of his own brain. To do this, is to corrupt it in the highest degree; to blend with the oracles of God, impure dreams, fit only for the mouth of the devil! And yet it has been so frequently done, that scarce ever was any erroneous [heretical] opinion either invented or received, but Scripture was quoted to defend it. [2.] And when the imposture was too bare-faced, and the text cited for it appeared too plainly either to make against it, or to be nothing to the purpose, then recourse has usually been had to a Second method of corrupting it, by mixing it with false interpretations. And this is done, sometimes by repeating the words wrong; and sometimes by repeating them right, but putting a wrong sense upon them; one that is either strained and unnatural, or foreign to the writer's intention in the place from whence they are taken; perhaps contrary either to his intention in that very place, or to what he says in some other part of his writings. And this is easily effected: Any passage is easily perverted, by being recited singly, without any of the preceding orfollowing verses. By this means it may often seem to have one sense, when it will be plain, by observing what goes before and what follows after, that it really has the direct contrary: For want of observing which, unwary souls are liable to be tossed about with every wind of doctrine, whenever they fall into the hand of those who have enough of wickedness and cunning, thus to adulterate what they preach, and to add now and then a plausible comment to make it go down the more easily.[3.] A Third sort of those who corrupt the Word of God, though in a lower degree than either of the former, are those who do so, not by adding to it, but taking from it; who take either of the spirit or substance of it away, while they study to prophesy only smooth things, and therefore palliate and colour what they preach, to reconcile it to the taste of the hearers. And that they may do this the better, they commonly let those parts go that will admit of no colouring. They wash their hands of those stubborn texts that will not bend to their purpose, or that too plainly touch on the reigning vices of the place where they are. These they exchange for those more soft and tractable ones, that are not so apt to give offence. Not one word must be said of the tribulation and anguish denounced against sinners in general; much less of the unquenchable fire, which, if God be true, awaits several of those particular offences that have fallen within their own notice. These tender parts are not to be touched without danger by them who study to recommend themselves to men; or, if they are, it must be with the utmost caution, and a nice evasion in reserve. But they safely may thunder against those who are out of their reach, and against those sins which they suppose none that hear them are guilty of. No one takes it to heart, to hear those practices laid open which he is not concerned in himself. But when the stroke comes home, when it reaches his own case, then is he, if not convinced, displeased, or angry, and out of patience.These are the methods of those corrupters of the word, who act in the sight of men, not of God. He trieth the hearts, and will receive no service in which the lips only are concerned. But their words have no intercourse with their thoughts. Nor is it proper for them that they should. For if their real intention once appeared, it must make itself unsuccessful. They purpose, it is true, to do good by the gospel of Christ; but it is to themselves, not to others. Whereas they that use sincerity in preaching the gospel, in the good of others seek their own. And that they are sincere, and speak as commissioned officers, in the sight of Him whose commission they bear, plainly appears from the direct contrariety between their practice, and that of the dissemblers above described.[II. 1.] First. Consider, it is not their own word they preach, but the word of Him that sent them. They preach it genuine and unmixed. As theydo not only profess, but really believe, that, "if any man add unto the word of God, He will add unto him all the plagues that are written in it," they are fearful of doing it in the least instance. You have the gospel from them, if in a less elegant manner, yet fair, and as it is; without any mixture of errors [heresy] to pollute it, or misinterpretation to perplex it; [2.] explained in the most natural, obvious manner, by what precedes and what follows the place in question; and commented on by the most sure way, the least liable to mistake or corruption, the producing of those parallel places that express the same thing the more plainly.[3.] In the next place, they are as cautious of taking from, as of adding to, the word they preach. They dare no more, considering in whose sight they stand, say less, than [or] more, than He has assigned them. They must publish, as proper occasions offer, all that is contained in the oracles of God; whether smooth or otherwise, it matters nothing, since it is unquestionably true, and useful too: "For all Scripture is given by inspiration of God; and is profitable either for doctrine, or reproof, or correction, or instruction in righteousness," -- either to teach us what we are to believe or practise, or for conviction of error, reformation of vice. They know that there is nothing superfluous in it, relating either to faith or practice; and therefore they preach all parts of it, though those more frequently and particularly which are more particularly wanted where they are. They are so far from abstaining to speak against any vice because it is fashionable and in repute in the place Providence has allotted them; but for that very reason they are more zealous in testifying against it. They are so far from abstaining from speaking for any virtue because it is unfashionable and in disrepute where they are placed, that they therefore the more vigorously recommend it.[4.] Lastly. They who speak in sincerity, and as in the sight of Him who deputes them, show that they do so, by the manner in which they speak. They speak with plainness and boldness, and are not concerned to palliate their doctrine, to reconcile it to the tastes of men. They endeavour to set it always in a true light, whether it be a pleasing one or not. They will not, they dare not, soften a threatening, so as to prejudice its strength, neither represent sin in such mild colours as to impair its native blackness. Not that they do not choose mildness, when it is likely to be effectual. Though they know "the terrors of the Lord," they desire rather to "persuade men." This method they use, and love to use it, with such as are capable of persuasion. With such as are not, they are obliged, if they will be faithful, to take the severer course. Let the revilers look to that; it harms not them: and if they are blamed or reviled for so doing, let the revilers look to that: Let the hearers accommodate themselves to the word; the word is not, in this sense, to be accommodatedto the hearers. The Preacher of it would be no less in fault, in a slavish obsequiousness on one side, than in an unrelenting sternness on the other.[III. 1.] If, then, we have spoken the word of God, the genuine unmixed word of God, and that only; if we have put no unnatural interpretation upon it, but [have] taken the known phrases in their common, obvious sense, -- and when they were less known, explained scripture by scripture; if we have spoken the whole word, as occasion offered, though rather the parts which seemed most proper to give a check to some fashionable vice, or to encourage the practice of some unfashionable virtue; and if we have done this plainly and boldly, though with all the mildness and gentleness that the nature of the subject will bear; -- then, believe ye our works, if not our words; or rather, believe them both together. Here is all a Preacher can do; all the evidence that he either can or need give of his good intentions. There is no way but this to show he speaks as of sincerity, as commissioned by the Lord, and as in his sight. If there be any who, after all this, will not believe that it is his concern, not our own, we labour for; that our first intention in speaking, is to point him the way to happiness, and to disengage him from the great road that leads to misery; we are clear of the blood of that man; -- it rests on his own head. For thus saith the Lord, who hath set us as watchmen over the souls of our countrymen and brethren: "If thou warn the wicked of his way to turn from it;" -- much more if we use all methods possible to convince him that the warning is of God; -- "if he do not turn from his way," -- which certainly he will not, if he do not believe that we are in earnest, -- "he shall die in his iniquity, but thou hast delivered thine own soul." [Section numbers (and other bracketed insertions of more significant textual variants) follow the Bicentennial Edition.][Edited by George Lyons for the Wesley Center for Applied Theology of Northwest Nazarene College (Nampa, ID).]。

^John Wesley^SERMON 90[text from the 1872 edition]AN ISRAELITE INDEED "Behold an Israelite indeed, in whom is no guile." John 1:47.1. Some years ago a very ingenious man, Professor Hutcheson of Glasgow, published two treatises, The Original of our Ideas of Beauty and Virtue. In the latter of these he maintains that the very essence of virtue is, the love of our fellow-creatures. He endeavours to prove, that virtue and benevolence are one and the same thing; that every temper is only so far virtuous, as it partakes of the nature of benevolence; and that all our words and actions are then only virtuous, when they spring from the same principle. "But does he not suppose gratitude, or the love of God to be the foundation of this benevolence?" By no means: Such a supposition as this never entered into his mind. Nay, he supposes just the contrary: He does not make the least scruple to aver, that if any temper or action be produced by any regard to God, or any view to a reward from him, it is not virtuous at all; and that if an action spring partly from benevolence and partly from a view to God, the more there is in it of a view to God, the less there is of virtue.2. I cannot see this beautiful essay of Mr. Hutcheson's in any other light than as a decent, and therefore more dangerous, attack upon the whole of the Christian Revelation: Seeing this asserts the love of God to be the true foundation, both of the love of neighbour, and all other virtues; and, accordingly, places this as "the first and great commandment," on which all the rest depend, "Thou shalt love the Lord thy God will all thy heart, and with all thy mind, and with all thy soul, and with all thy strength." So that, according to the Bible, benevolence, or the love of our neighbour, is only the second commandment. And suppose the Scripture be of God, it is so far from being true, that benevolence alone is both the foundation and the essence of all virtue, that benevolence itself is no virtue at all, unless it spring from the love of God3. Yet it cannot be denied, that this writer himself has a marginal note in favour of Christianity. "Who would not wish," says he, "that the Christian Revelation could be proved to be of God? Seeing it is, unquestionably, the most benevolent institution that ever appeared in the world!" But is not this, if it be considered thoroughly, another blow atthe very root of that Revelation? Is it more or less than to say: "I wish it could; but in truth it cannot be proved."4. Another ingenious writer advances an hypothesis totally different from this. Mr. Wollaston, in the book which he entitles, "The Religion of Nature Delineated," endeavours to prove, that truth is the essence of virtue, or conformableness to truth. But it seems, Mr. Wollaston goes farther from the Bible than Mr. Hutcheson himself. For Mr. Hutcheson's scheme sets aside only one of the two great commandments, namely, "Thou shalt love the Lord thy God;" whereas Mr. Wollaston sets aside both: For his hypothesis does not place the essence of virtue in either the love of God or of our neighbour.5. However, both of these authors agree, though in different ways, to put asunder what God has joined. But St. Paul unites them together in teaching us to "speak the truth in love." And undoubtedly, both truth and love were united in him to whom He who knows the hearts of all men gives this amiable character, "Behold an Israelite indeed, in whom is no guile!"6. But who is it, concerning whom our blessed Lord gives this glorious testimony? Who is this Nathanael, of whom so remarkable an account is given in the latter part of the chapter before us? [John 1] Is it not strange that he is not mentioned again in any part of the New Testament? He is not mentioned again under this name; but probably he had another, whereby he was more commonly called. It was generally believed by the ancients, that he is the same person who is elsewhere termed Bartholomew; one of our Lord's Apostles, and one that, in the enumeration of them, both by St. Matthew and St. Mark, is placed immediately after St. Philip, who first brought him to his Master. It is very probable, that his proper name was Nathanael, -- a name common among the Jews; and that his other name, Bartholomew, meaning only the son of Ptolemy, was derived from his father, a custom which was then exceeding common among the Jews, as well as the Heathens.7. By what little is said of him in the context he appears to have beena man of an excellent spirit; not hasty of belief, and yet open to conviction, and willing to receive the truth, from whencesoever it came. So we read, (John 1:45,) "Philip findeth Nathanael," (probably by what we term accident,) "and saith unto him, "We have found him, of whom Moses in the Law, and the Prophets, did write, Jesus of Nazareth." "Nathanael saith unto him, Can any good thing come out of Nazareth?" Has Moses spoke, or did the Prophets write, of any prophet to come from thence? "Philip saith unto him, Come and see;" and thou wilt soon be able to judge for thyself. Nathanael took his advice, without staying to confer with flesh and blood. "Jesus saw Nathanael coming, and saith, Behold an Israeliteindeed, in whom is no guile!" "Nathanael saith," doubtless with surprise enough, "Whence knowest thou me?" Jesus saith, Before Philip called thee, when thou wast under the fig-tree, I saw thee." "Nathanael answered and said unto him," -- so soon was all prejudice gone! -- "Rabbi, thou art the Son of God; thou art the King of Israel."But what is implied in our Lord's character of him? "In whom is no guile." It may include all that is contained in that advice, --Still let thy heart be true to God,Thy words to it, thy actions to them both.I. 1. We may, First, observe what is implied in having our hearts true to God. Does this imply any less than is included in that gracious command, "My son, give me thy heart?" Then only is our heart true to God, when we give it to him. We give him our heart, in the lowest degree, when we seek our happiness in him; when we do not seek it in gratifying "the desire of the flesh," -- in any of the pleasures of sense; nor in gratifying "the desire of the eye," -- in any of the pleasures of the imagination, arising from grand, or new, or beautiful objects, whether of nature or art; neither in "the pride of life," -- in "the honour that cometh of men," in being beloved, esteemed, and applauded by them; no, nor yet in what some term, with equal impudence and ignorance, the main chance, the "laying up treasures on earth." When we seek happiness in none of these, but in God alone, then we, in some sense give him our heart.2. But in a more proper sense, we give God our heart, when we not only seek but find happiness in him. This happiness undoubtedly begins, when we begin to know him by the teaching of his own Spirit; when it pleases the Father to reveal his Son in our hearts, so that we can humbly say, "My Lord and my God;" and when the Son is pleased to reveal his Father in us, by "the Spirit of adoption, crying in our hearts, Abba Father," and "bearing his "testimony to our spirits, that we are the children of God." Then it is that "the love of God also is shed abroad in our hearts." And according to the degree of our love, is the degree of our happiness.3. But it has been questioned, whether it is the design of God, that the happiness which is at first enjoyed by all that know and love him, should continue any longer than, as it were, the day of their espousals. In very many, we must allow, it does not; but in a few months, perhaps weeks, or even days, the joy and peace either vanishes at once, or gradually decays. Now, if God is willing that their happiness should continue, how is this to be accounted for?4. I believe, very easily: St. Jude's exhortation, "Keep yourselves in the love of God," certainly implies that something is to be done on our part in order to its continuance. And is not this agreeable to that general declaration of our Lord, concerning this and every gift of God? "Unto him that hath shall be given, and he shall have more abundance: But from him that hath not," that is, uses it not, improves it not, "shall be taken away even that which he hath." (Luke 8:18.)5. Indeed, part of this verse is translated in our version, "That which he seemeth to have." But it is difficult to make sense of this. For if he only seemeth to have this, or any other gift of God, he really hath it not. And if so, it cannot be taken away: For no man can lose what he never had. It is plain, therefore, _ho dokei echein_, ought to be rendered, what he assuredly hath. And it may be observed, that the word _dokeO_ in various places of the New Testament does not lessen, but strengthens the sense of the word joined with it. Accordingly, whoever improves the grace he has already received, whoever increases in the love of God, will surely retain it. God will continue, yea, will give it more abundantly; Whereas, whoever does not improve this talent, cannot possibly retain it. Notwithstanding all he can do, it will infallibly be taken away from him.II. 1. Meantime, as the heart of him that is "an Israelite indeed" is true to God, so his words are suitable thereto: And as there is no guile lodged in his heart, so there is none found in his lips. The first thing implied herein, is veracity, -- the speaking the truth from his heart, -- the putting away all wilful lying, in every kind and degree. A lie, according to a well-known definition of it, is, _falsum testmonium, cum intentione fallendi: "A falsehood, known to be such by the speaker, and uttered with an intention to deceive." But even the speaking a falsehood is not a lie, if it be not spoken with an intent to deceive.2. Most casuists, particularly those of the Church of Rome, distinguish lies into three sorts: The First sort is malicious lies; the Second, harmless lies; the Third, officious lies: Concerning which they pass a very different judgment. I know not any that are so hardy as even to excuse, much less defend, malicious lies; that is, such as are told with a design to hurt any one: These are condemned by all parties. Men are more divided in their judgment with regard to harmless lies, such as are supposed to do neither good nor harm. The generality of men, even in the Christian world, utter them without any scruple, and openly maintain, that, if they do no harm to anyone else, they do none to the speaker. Whether they do or no, they have certainly no place in the mouth of him that is "an Israelite indeed." He cannot tell lies in jest, am more than in earnest. Nothing but truth is heard from his mouth. He remembers the express commandof God to the Ephesian Christians: "Putting away lying, speak every man truth to his neighbour." (Eph. 4:25.)3. Concerning officious lies, those that are spoken with a design to do good, there have been numerous controversies in the Christian Church. Abundance of writers, and those men of renown, for piety as well as learning, have published whole volumes upon the subject, and, in despite of all opposers, not only maintained them to be innocent, but commended them as meritorious. But what saith the Scripture? One passage is so express that there does not need any other. It occurs in the third chapter of the Epistle to the Romans, where the very words of the Apostle are: (Rom. 3: 7, 8,) "If the truth of God hath more abounded through my lie unto his glory, why am I yet judged as a sinner?" (Will not that lie be excused from blame, for the good effect of it?) "And not rather, as we are slanderously reported, and as some affirm that we say, Let us do evil, that good may come? Whose damnation is just." Here the Apostle plainly declares, (1.) That the good effect of a lie is no excuse for it. (2.) That it is a mere slander upon Christians to say, "They teach men to do evil that good may come." (3.) That if any, in fact, do this; either teach men to do evil that good may come, or do so themselves; their damnation is just. This is peculiarly applicable to those who tell lies in order to do good thereby. It follows, that officious lies, as well as all others, are an abomination to the God of truth. Therefore, there is no absurdity, however strange it may sound, in that saying of the ancient Father, "I would not tell a wilful lie, to save the souls of the whole world."4. The second thing which is implied in the character of "an Israelite indeed," is, sincerity. As veracity is opposite to lying, so sincerity is to cunning. But it is not opposite to wisdom, or discretion, which are well consistent with it. "But what is the difference between wisdom and cunning? Are they not almost, if not quite, the same thing?" By no means. The difference between them is exceeding great. Wisdom is the faculty of discerning the best ends, and the fittest means of attaining them. The end of every rational creature is God: the enjoying him in time and in eternity. The best, indeed the only, means of attaining this end, is "the faith that worketh by love." True prudence, in the general sense of the word, is the same thing with wisdom. Discretion is but another name for prudence, -- if it be not rather a part of it, as it sometimes is referred to our outward behaviour, -- and means, the ordering our words and actions right. On the contrary, cunning (so it is usually termed amongst common men, but policy among the great) is, in plain terms, neither better nor worse than the art of deceiving. If therefore, it be any wisdom at all, it is "the wisdom from beneath;" springing from the bottomless pit, and leading down to the place from whence it came.5. The two great means which cunning uses in order to deceive, are, simulation and dissimulation.Simulation is the seeming to be what we are not; dissimulation, the seeming not to be what we are; according to the old verse, _Quod non est simulo: Dissimuloque quod est._ Both the one and the other we commonly term, the "hanging out of false colours." Innumerable are the shapes that simulation puts on in order to deceive. And almost as many are used by dissimulation for the same purpose. But the man of sincerity shuns them both, and always appears exactly what he is.6. "But suppose we are engaged with artful men, may we not use silence or reserve, especially if they ask insidious questions, without falling under the imputation of cunning?" Undoubtedly we may: Nay, we ought on many occasions either wholly to keep silence, or to speak with more or less reserve, as circumstances may require. To say nothing at all, is, in many cases, consistent with the highest sincerity. And so it is, to speak with reserve, to say only a part, perhaps a small part, of what we know. But were we to pretend it to be the whole, this would be contrary to sincerity.7. A more difficult question than this is, "May we not speak the truth in order to deceive? like him of old, who broke out into that exclamation applauding his own ingenuity, _Hoc ego mihi puto palmarium, ut vera dicendo eos ambos fallam._ `This I take to be my master-piece, to deceive them both by speaking the truth!" I answer, A Heathen might pique himself upon this; but a Christian could not. For although this is not contrary to veracity, yet it certainly is to sincerity. It is therefore the most excellent way, if we judge it proper to speak at all, to put away both simulation and dissimulation, and to speak the naked truth from our heart.8. Perhaps this is properly termed, simplicity.It goes a little farther than sincerity itself. It implies not only, First, the speaking no known falsehood; and, Secondly, the not designedly deceiving any one; but, Thirdly, the speaking plainly and artlessly to everyone when we speak at all; the speaking as little children, in a childlike, though not a childish, manner. Does not this utterly exclude the using any compliments? A vile word, the very sound of which I abhor; quite agreeing with our poet: --It never was a good daySince lowly fawning was call'd compliment.I advise men of sincerity and simplicity never to take that silly word in their mouth; but labour to keep at the utmost distance both from the name and the thing.9. Not long before that remarkable time,When Statesmen sent a Prelate 'cross the seas,By long-famed Act of pains and penalties,several Bishops attacked Bishop Atterbury at once, then Bishop of Rochester, and asked, "My Lord, why will you not suffer your servants to deny you, when you do not care to see company? It is not a lie for them to say your lordship is not at home; for it deceives no one: Every one knows it means only, your lordship is busy." He replied, "My Lords, if it is (which I doubt) consistent with sincerity, yet I am sure it is not consistent with that simplicity which becomes a Christian Bishop."10. But to return. The sincerity and simplicity of him in whom is no guile have likewise an influence on his whole behaviour: They give a colour to his whole outward conversation; which, though it be far remote from everything of clownishness and ill-breeding, of roughness and surliness, yet is plain and artless, and free from all disguise, being the very picture of his heart. The truth and love which continually reign there, produce an open front, and a serene countenance; such as leave no pretence to say, with that arrogant King of Castile, "When God made man, he left one capital defect: He ought to have set a window in his breast;" -- for he opens a window in his own breast, by the whole tenor of his words and actions.11. This then is real, genuine, solid virtue. Not truth alone, nor conformity to truth. This is a property of real virtue, not the essence of it. Not love alone; though this comes nearer the mark: For love, in one sense, "is the fulfilling of the law." No: Truth and love united together, are the essence of virtue or holiness. God indispensably requires "truth in the inward parts," influencing all our words and actions. Yet truth itself, separate from love, is nothing in his sight. But let the humble, gentle, patient love of all mankind, be fixed on its right foundation, namely, the love of God springing from faith, from a full conviction that God hath given his only Son to die for my sins; and then the whole will resolve into that grand conclusion, worthy of all men to be received: "Neither circumcision availeth any thing, nor uncircumcision, but faith that worketh by love."[Edited by George Lyons for the Wesley Center for Applied Theology at Northwest Nazarene College (Nampa, ID).]。

John WesleySERMON 5(text from the 1872 edition)JUSTIFICATION BY FAITH"To him that worketh not,but believeth on him that justifieth the ungodly,his faith is counted for righteousness。

" Romans 4:5. 1. How a sinner may be justified before God, the Lord and Judge of all, is a question of no common importance to every child of man。

It contains the foundation of all our hope,inasmuch as while we are at enmity with God, there can be no true peace,no solid joy, either in time or in eternity。

What peace can there be,while our own heart condemns us;and much more,He that is ”greater than our heart, and knoweth all things?” What solid joy,either in this world or that to come,while "the wrath of God abideth on us?"2. And yet how little hath this important question been understood!What confused notions have many had concerning it!Indeed, not only confused, but often utterly false; contrary to the truth,as light to darkness;notions absolutely inconsistent with the oracles of God, and with the whole analogy of faith。

John WesleySERMON 131[text from the 1872 edition]THE LATE WORK OF GOD IN NORTH AMERICA"The appearance was as it were a wheel in the middle of a wheel." Ezek. 1:16.1. Whatever may be the primary meaning of this mysterious passage of Scripture, many serious Christians, in all ages have applied it in a secondary sense, to the manner wherein the adorable providence of God usually works in governing the world. They have judged this expression manifestly to allude to the complicated wheels of his providence, adapting one event to another, and working one thing by means of another. In the whole process of this, there is an endless variety of wheels within wheels. But they are frequently so disposed and complicated, that we cannot understand them at first sight; nay, we can seldom fully comprehend them till they are explained by the event.2. Perhaps no age ever afforded a more striking instance of this kind than the present does, in the dispensations of divine providence with respect to our colonies in North-America. In order to see this clearly, let us endeavour, according to the measure of our weak understanding,First, to trace each wheel apart: And,Secondly, to consider both, as they relate to and answer each other.I. And, First, we are to trace each wheel apart.It is by no means my design to give a particular detail of the late transactions in America; but barely to give a simple and naked deduction of a few well-known facts.I know this is a very delicate subject; and that it is difficult, if not impossible, to treat it in such a manner as not to offend any, particularly those who are warmly attached to either party. But I would not willingly offend; and shall therefore studiously avoid all keen and reproachfullanguage, and use the softest terms I can, without either betraying or disguising the truth.1. In the year 1736 it pleased God to begin a work of grace in the newly planted colony of Georgia, then the southernmost of our settlements on the continent of America. To those English who had settled there the year before, were then added a body of Moravians, so called; and a larger body who had been expelled from Germany by the Archbishop of Salzburg. These were men truly fearing God and working righteousness. At the same time there began an awakening among the English, both at Savannah and Frederica; many inquiring what they must do to be saved, and "bringing forth fruits meet for repentance."2. In the same year there broke out a wonderful work of God in several parts of New-England. It began in Northampton, and in a little time appeared in the adjoining towns. A particular and beautiful account of this was published by Mr. Edwards, Minister of Northampton. Many sinners were deeply convinced of sin, and many truly converted to God. I suppose there had been no instance in America of so swift and deep a work of grace, for an hundred years before; nay, nor perhaps since the English settled there.3. The following year, the work of God spread by degrees from New-England towards the south. At the same time it advanced by slow degrees, from Georgia towards the north. In a few souls it deepened likewise; and some of them witnessed a good confession, both in life and in death.4. In the year 1738 Mr. Whitefield came over to Georgia, with a design to assist me in preaching, either to the English or the Indians. But as I was embarked for England before he arrived, he preached to the English altogether, first in Georgia, to which his chief service was due, then in South and North Carolina, and afterwards in the intermediate provinces, till he came to New-England. And all men owned that God was with him, wheresoever he went; giving a general call to high and low, rich and poor, to "repent, and believe the gospel." Many were not disobedient to the heavenly calling: They did repent and believe the gospel. And by his ministry a line of communication was formed, quite from Georgia to New-England.5. Within a few years he made several more voyages to America, and took several more journeys through the provinces. And in every journey he found fresh reason to bless God, who still prospered the work of his hands; there being more and more, in all the provinces, who found his word to be "the power of God unto salvation."6. But the last journey he made, he acknowledged to some of his friends, that he had much sorrow and heaviness in his heart, on account of multitudes who for a time ran well, but afterwards "drew back unto perdition." Indeed, in a few years, the far greater part of those who had once "received the word with joy," yea, had "escaped the corruption that is in the world," were "entangled again and overcome." Some were like those who received the seed on stony ground, which "in time of temptation withered away." Others were like those who "received it among thorns: "the thorns" soon "sprang up, and choked it." Insomuch that he found exceeding few who "brought forth fruit to perfection." A vast majority had entirely "turned back from the holy commandment delivered to them."7. And what wonder! for it was a true saying, which was common in the ancient Church, "The soul and the body make a man; and the spirit and discipline make a Christian." But those who were more or less affected by Mr. Whitefield's preaching had no discipline at all. They had no shadow of discipline; nothing of the kind. They were formed into no societies: They had no Christian connection with each other, nor were ever taught to watch over each other's souls. So that if any fell into lukewarmness, or even into sin, he had none to lift him up: He might fall lower and lower, yea, into hell, if he would, for who regarded it?8. Things were in this state when about eleven years ago I received several letters from America, giving a melancholy account of the state of religion in most of the colonies, and earnestly entreating that some of our Preachers would come over and help them. It was believed they might confirm many that were weak or wavering, and lift up many that were fallen; nay, and that they would see more fruit of their labours in America than they had done either in England or Ireland.9. This was considered at large in our yearly Conference at Bristol, in the year 1769: And two of our Preachers willingly offered themselves; viz., Richard Boardman and Joseph Pillmoor. They were men well reported of by all, and (we believed) fully qualified for the work. Accordingly, after a few days spent in London, they cheerfully went over. They laboured first in Philadelphia and New-York; afterwards in many other places: And everywhere God was eminently with them, and gave them to see much fruit of their labour. What was wanting before was now supplied: Those who were desirous to save their souls were no longer a rope of sand, but clave to one another, and began to watch over each other in love. Societies were formed, and Christian discipline introduced in all its branches. Within a few years after, several more of the Preachers were willing to go and assist them. And God raised up many natives of the country who were glad to act in connexion with them; till there were two-and-twenty TravellingPreachers in America, who kept their circuits as regularly as those in England.10. The work of God then not only spread wider, particularly in North Carolina, Maryland, Virginia, Pennsylvania, and the Jerseys, but sunk abundantly deeper than ever it had done before. So that at the beginning of the late troubles there were three thousand souls connected together in religious societies; and a great number of these witnessed that the Son of God hath power on earth to forgive sin.11. But now it was that a bar appeared in the way, a grand hindrance to the progress of religion. The immense trade of America, greater in proportion than even that of the mother-country, brought in an immense flow of wealth; which was also continually increasing. Hence both merchants and tradesmen of various kinds accumulated money without end, and rose from indigence to opulent fortunes, quicker than any could do in Europe. Riches poured in upon them as a flood, and treasures were heaped up as the sand of the sea. And hence naturally arose unbounded plenty of all the necessaries, conveniences, yea, and superfluities, of life.12. One general consequence of this was pride. The more riches they acquired, the more they were regarded by their neighbours as men of weight and importance: And they would naturally see themselves in at least as fair a light as their neighbours saw them. And, accordingly, as they rose in the world, they rose in their opinion of themselves. As it is generally allowed,A thousand pound suppliesThe want of twenty thousand qualities;so, the richer they grew, the more admiration they gained, and the more applause they received. Wealth then bringing in more applause, of course brought in more pride, till they really thought themselves as much wiser, as they were wealthier, than their neighbours.13. Another natural consequence of wealth was luxury, particularly in food. We are apt to imagine nothing can exceed the luxurious living which now prevails in Great Britain and Ireland. But alas! what is this to that which lately prevailed in Philadelphia, and other parts of North America? A merchant or middling tradesman there kept a table equal to that of a nobleman in England; entertaining his guests with ten, twelve, yea, sometimes twenty dishes of meat at a meal! And this was so far from being blamed by any one, that it was applauded as generosity and hospitality.14. And is not idleness naturally joined with "fullness of bread?" Doth not sloth easily spring from luxury? It did so here in an eminent degree;such sloth as is scarce named in England. Persons in the bloom of youth, and in perfect health, could hardly bear to put on their own clothes. The slave must be called to do this, and that, and everything: It is too great labour for the master or mistress. It is a wonder they would be at the pains of putting meat into their own mouths. Why did they not imitate the lordly lubbers in China, who are fed by a slave standing on each side?15. Who can wonder, if sloth alone beget wantonness? Has it not always had this effect? Was it not said near two thousand years ago,_Quaeritur, Aegisthus quare sit factus adulter?In promptu causa est; Desidiosus erat.[The following is Tate's translation of this quotation from Ovid: --"The adulterous lust that did Aegisthus seize,And brought on murder, sprang from wanton ease." -- Edit.]And when sloth and luxury are joined together, will they not produce an abundant offspring? This they certainly have done in these parts. I was surprised a few years ago at a letter I received from Philadelphia, wherein were (nearly) these words: "You think the women in England (many of them, I mean) do not abound in chastity. But yet the generality of your women, if compared with ours, might almost pass for vestal virgins." Now this complication of pride, luxury, sloth, and wantonness, naturally arising from vast wealth and plenty, was the grand hindrance to the spreading of true religion through the cities of North-America.II. Let us now see the other wheel of divine providence.1. It may reasonably be supposed that the colonies in New-England had, from their very beginning, an hankering after independency. It could not be expected to be otherwise, considering their families, their education, their relations, and the connections they had formed before they left their native country. They were farther inclined to it by the severe and unjust treatment which many of them had met with in England. This might well create in them a fear lest they should meet with the like again, a jealousy of their governors, and a desire of shaking off that dependence, to which they were never thoroughly reconciled. The same spirit they communicated to their children, from whom it descended to the present generation. Nor could it be effaced by all the favours and benefits which they continually received from the English Government.2. This spirit generally prevailed, especially in Boston, as early as the year 1737. In that year, my brother, being detained there some time, wasgreatly surprised to hear almost in every company, whether of Ministers, gentlemen, merchants, or common people, where anything of the kind was mentioned, "We must be independent! We will be independent! We will bear the English yoke no longer! We will be our own governors!" This appeared to be even then the general desire of the people; although it is not probable that there was at that time any formed design. No; they could not be so vain as to think they were able to stand alone against the power of Great Britain.3. A gentleman who was there in the following year observed the same spirit in every corner of the town: "Why should these English blockheads rule over us?" was then the common language. And as one encouraged another herein, the spirit of independency rose higher and higher, till it began to spread into the other colonies bordering upon New-England. Nevertheless the fear of their troublesome neighbours, then in possession of Canada, kept them within bounds, and for a time prevented the flame from breaking out. But when the English had removed that fear from them, when Canada was ceded to the king of Great Britain, the desire then ripened into a formed design; only a convenient opportunity was wanting.4. It was not long before that opportunity appeared. The Stamp-Act was passed, and sent over to America. The malcontents saw and pressed their advantage; they represented it as a common cause; and by proper emissaries spread their own spirit through another and another colony. By inflammatory papers of every kind, they stirred up the minds of the people. They vilified, first, the English Ministry, representing them, one and all, as the veriest wretches alive, void of all honesty, honour, and humanity. By the same methods they next inflamed the people in general against the British Parliament, representing them as the most infamous villains upon earth, as a company of base, unprincipled hirelings. But still they affected to reverence the King, and spoke very honourably of him. Not long; a few months after, they treated him in the same manner they had done his ministers and his Parliament.5. Matters being now, it was judged, in sufficient forwardness, an association was formed between the northern and southern colonies; both took up arms, and constituted a supreme power which they termed the Congress. But still they affirmed, their whole design was to secure their liberty; and even to insinuate that they aimed at anything more, was said to be quite cruel and unjust. But in a little time they threw off the mask, and boldly asserted their own independency. Accordingly, Dr. Witherspoon, President of the College in New-Jersey, in his address to the Congress (added to a Fast-Sermon, published by him, August 3, 1776,) uses the following words: -- "It appears now, in the clearest manner, that till very lately those who seemed to take the part of America, in the BritishParliament, never did it on American principles. They either did not understand, or were not willing to admit, the extent of our claim. Even the great Lord Chatham's Bill for Reconciliation would not have been accepted here, and did not materially differ from what the Ministry would have consented to." Here it is avowed, that their claim was independency; and that they would accept of nothing less.6. By this open and avowed defection from, and defiance of, their mother-country, (whether it was defensible or not, is another question,) at least nine parts in ten of their immense trade to Europe, Asia, Africa, and other parts of America were cut off at one stroke. In lieu of this they gained at first, perhaps, an hundred thousand pounds a year by their numerous privateers. But even then, this was, upon the whole, no gain at all; for they lost as many ships as they took. Afterwards they took fewer and fewer; and in the meantime they lost four or five millions yearly, (perhaps six or seven,) which their trade brought them in. What was the necessary consequence of this? Why, that, as the fountain of their wealth was dammed up, the streams of it must run lower and lower, till they were wholly exhausted; so that at present these provinces are no richer than the poorest parts either of Scotland or Ireland.7. Plenty declined in the same proportion as wealth, till universal scarcity took place. In a short time there was everywhere felt a deep want, not only of the superfluities, not only of the common conveniences, but even of the necessaries, of life. Wholesome food was not to be procured but at a very advanced price. Decent apparel was not to be had, not even in the large towns. Not only velvets, and silks, and fashionable ornaments, (which might well be spared,), but even linen and woollen clothes, were not to be purchased at any price whatsoever.8. Thus have we observed each of these wheels apart; -- on the one hand, trade, wealth, pride, luxury, sloth, and wantonness spreading far and wide, through the American provinces; on the other, the spirit of independency diffusing itself from north to south.Let us now observe how each of these wheels relates to, and answers, the other; how the wise and gracious providence of God uses one to check the course of the other, and even employs (if so strong an expression may be allowed) Satan to cast out Satan. Probably, that subtle spirit hoped, by adding to all those other vices the spirit of independency, to have overturned the whole work of God, as well as the British Government, in North-America. But he that sitteth in heaven laughed him to scorn, and took the wise in his own craftiness. By means of this very spirit, there is reason to believe, God will overturn every hindrance of that work.9. We have seen, how by the breaking out of this spirit, in open defiance of the British Government, an effectual check was given to the trade of those colonies. They themselves, by a wonderful stroke of policy, threw up the whole trade of their mother-country, and all its dependencies; made an Act, that no British ship should enter into any of their harbours; nay, they fitted out numberless privateers, which seized upon all the British ships they could find. The King's ships seized an equal number of theirs. So their foreign trade too was brought almost to nothing. Their riches died away with their trade, especially as they had no internal resources; the flower of their youth, before employed in husbandry, being now drawn off into their armies, so that the most fruitful lands were of no use, none being left to till the ground. And when wealth fled away, (as was before observed,) so did plenty too; -- abundance of all things being succeeded by scarcity of all things.10. The wheel now began to move within the wheel. The trade and wealth of the Americans failing, the grand incentives of pride failed also; for few admire or flatter the poor. And, being deserted by most of their admirers, they did not altogether so much admire themselves; especially when they found, upon the trial, that they had grievously miscalculated their own strength; which they had made no doubt would be sufficient to carry all before it. It is true, many of them still exalted themselves; but others were truly and deeply humbled.11. Poverty, and scarcity consequent upon it, struck still more directly at the root of their luxury. There was no place now for that immoderate superfluity either of food or apparel. They sought no more, and could seldom obtain, so much as plain food, sufficient to sustain nature. And they were content if they could procure coarse apparel, to keep them clean and warm. Thus they were reduced to the same condition their forefathers were in when the providence of God brought them into this country. They were nearly in the same outward circumstances. Happy, if they were likewise in the same spirit!12. Poverty and want struck at the root of sloth also. It was now no time to say, "A little more sleep, a little more slumber, a little more folding of the hands to rest." If a man would not work now, it was plain he could not eat. All the pains he could take were little enough to procure the bare necessaries of life: Seeing, on the one hand, so few of them remained, their own armies having swept away all before them; and, on the other, what remained bore so high a price, that exceeding few were able to purchase them.13. Thus, by the adorable providence of God, the main hindrances of his work are removed. And in how wonderful a manner; -- such as it never couldhave entered into the heart of man to conceive! Those hindrances had been growing up and continually increasing for many years. What God foresaw would prove the remedy grew up with the disease; and when the disease was come to its height, then only began to operate. Immense trade, wealth, and plenty begot and nourished proportionable pride, and luxury, and sloth, and wantonness. Meantime the same trade, wealth, and plenty begot or nourished the spirit of independency. Who would have imagined that this evil disease would lay a foundation for the cure of all the rest? And yet so it was. For this spirit, now come to maturity, and disdaining all restraint, is now swiftly destroying the trade, and wealth, and plenty whereby it was nourished, and thereby makes way for the happy return of humility, temperance, industry, and chastity. Such unspeakable good does the all-wise God bring out of all this evil! So does "the fierceness of man," of the Americans, "turn to his praise," in a very different sense from what Dr. Witherspoon supposes!14. May we not observe, how exactly in this grand scene of providence, one wheel answers to the other? The spirit of independency, which our poet so justly terms,The glorious fault of angels and of gods,(that is, in plain terms, of devils,) the same which so many call liberty, is over-ruled by the justice and mercy of God, first to punish those crying sins, and afterwards to heal them. He punishes them by poverty, coming as an armed man, and over-running the land; by such scarcity as has hardly been known there for an hundred years past; by want of every kind, even of necessary clothing, even of bread to eat. But with what intent does he do this? Surely that mercy may rejoice over judgment. He punishes that he may amend, that he may first make them sensible of their sins, which anyone that has eyes to see may read in their punishment; and then bring them back to the spirit of their forefathers, the spirit of humility, temperance, industry, chastity; yea, and a general willingness to hear and receive the word which is able to save their souls. "O the depth, both of the wisdom and knowledge of God! How unsearchable are his judgments, and his ways past finding out!" -- unless so far as they are revealed in his word, and explained by his providence.15. From these we learn that the spiritual blessings are what God principally intends in all these severe dispensations. He intends they should all work together for the destruction of Satan's kingdom, and the promotion of the kingdom of his dear Son; that they should all minister to the general spread of "righteousness, and peace, and joy in the Holy Ghost." But after the inhabitants of these provinces are brought again to "seek the kingdom of God, and his righteousness," there can be no doubt, but all other things, all temporal blessings, will be added unto them.He will send through all the happy land, with all the necessaries and conveniences of life, not independency, (which would be no blessing, but an heavy curse, both to them and their children,) but liberty, real, legal liberty; which is an unspeakable blessing. He will superadd to Christian liberty, liberty from sin, true civil liberty; a liberty from oppression of every kind; from illegal violence; a liberty to enjoy their lives, their persons, and their property; in a word, a liberty to be governed in all things by the laws of their country. They will again enjoy true British liberty, such as they enjoyed before these commotions: Neither less nor more than they have enjoyed from their first settlement in America. Neither less nor more than is now enjoyed by the inhabitants of their mother country. If their mother-country had ever designed to deprive them of this, she might have done it long ago; and that this was never done, is a demonstration that it was never intended. But God permitted this strange dread of imaginary evils to spread over all the people that he might have mercy upon all, that he might do good to all, by saving them from the bondage of sin, and bringing them into "the glorious liberty of the children of God!"[Edited by George Lyons for the Wesley Center for Applied Theology of Northwest Nazarene College (Nampa, ID).]。

持守拥有的位分经文:斯4:14此时你若闭口不言,犹大人必从别处得解脱,蒙拯救,你和你父家,必至灭亡。

焉知你得了王后的位分,不是为现今的机会吗?弟兄姊妹,今天我们分享的是旧约圣经《以斯帖记》四章14节的经文。

这节经文的背景是:当时犹大人被掳到外邦国家。

有一次,这个外邦国家的王亚哈随鲁受坏人哈曼的怂恿,下令要灭掉全国的犹大人。

刚被选为王后的犹大女子以斯帖的养父末底改托人叫以斯帖向王求救,当末底改托人让以斯帖找王的时候,以斯帖已经多日没有见王了。

那时在王宫里有这样的规定:如果王没有召你,你擅自见王,除非王向你伸出金杖赦免你,否则你就得灭亡。

所以以斯帖不敢去见王。

于是末底改就托人对她说了这样一句话:“此时你若闭口不言,犹大人必从别处得解脱,蒙拯救,你和你父家必至灭亡。

焉知你得了王后的位分,不是为现今的机会吗?”这节经文给了我们很大的启发。

弟兄姊妹,我们有没有想过,我们现在所处的是什么位分?一个基督徒?一个在神家里作“出口”的牧师?诗班成员?还是琴师?上帝给你的恩赐是什么?你自己的位分是什么?有时我们在神面前难以献上感恩的心,这是因为我们还没有认清自己的位分。

我们只有将神所赐的位分认清,认清自己罪人不配的身份才有感恩之心,有时人认不清自己的真实处境,所以无法感恩。

人所得到的一切都是神所赐的,可有时我们觉得不够,觉得上帝给的太少了,所以无法献上感恩。

比如一个孩子,如果没有认清自己所拥有的一切是父母给自己的,他就不会知足,总觉得父母为自己做什么都是应该的。

可是如果他真正认识到自己的位分,我想,他会为父母给他的一切献上感恩。

同样,当一个人认识到自己的不配时,他才能真正充满感恩地去做神的工。

所以我今天要和弟兄姐妹分享的就是:感恩人生——持守自己所处的位分一、认清自己所处的位分这是很重要的一点。

你要想做一个感恩的人,你一定要认识自己,认识自己所处的位分。

有的时候,我们觉得人生的每一步好像看起来没有什么目的,可是当我们在神的面前默想这一切的时候,我们才发现,我们所走的人生每一步都是上帝工作的效果,上帝在我们身上一步一步地做这些工作。

(完整word版)必修五unit1课文及译文(完好word版)必修五unit1课文及译文JOHN SNOW DEFEATS "KING CHOLERAJohn Snow was a famous doctor in London-so expert, indeed, that he attended Queen Victoria as her personal physician. But he became inspired when he thought about helping ordinary people exposed to cholera. This was the deadly disease of its day. Neither its cause nor its cure was understood. So many thousands of terrified people died every time there was an outbreak. John Snow wanted to face the challenge and solve this problem. He knew that cholera would never be controlled until its cause was found.约翰·斯洛是伦敦一位有名的医生--他确实医术精湛,因此成为照料维多利亚女王的私人医生。

但他一想到要帮助那些得了霍乱的一般百姓时,他就感到很振奋。

霍乱在当时是最致命的疾病,人们既不知道它的病源,也不了解它的治疗方法。

每次霍乱爆发时,就有大批惊恐的老百姓死去。

约翰·斯洛想面对这个挑战,解决这个问题。

他知道,在找到病源之前,霍乱疫情是无法掌握的。

He became interested in two theories that possibly explained how cholera killed people. The first suggested that cholera multiplied in the air. A cloud of dangerous gas floated around until it found its victims. The second suggested that people absorbed this disease into their bodieswith their meals. From the stomach the disease quickly attacked the body and soon the affected person died.斯洛对霍乱致人死地的两种推想都很感兴趣。