Tying in two-sided markets and the honor all cards rule

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:187.98 KB

- 文档页数:26

营销英语词汇大全1vertical marketing systems (VMS) 垂直营销系统vision 愿景Volvo 沃尔沃W Wall Street Journal 《华尔街日报》Wal-Mart 沃尔玛Walt Disney 迪斯尼want 欲求warranty 质量保证weight 加权Wella 维拉Wendys 温迪Whirlpool 惠而浦wholesale clubs 批发俱乐部wholesaler-sponsored voluntary chains 批发商发起的自愿连锁wholesaling trends 批发趋势win-back program 赢回(顾客)方案working capital investment 周转资金投入workload approach 计算工作量方法World Wide Web (WWW) 万维网X Xerox 施乐Y Yamaha 雅马哈young urban trend setters 年轻的城市潮流领导Z zero defect 零缺陷zone pricing 分区定价法营销英语词汇大全2 threat of new entrants 新进入者的威胁three order-hierarchy models 三阶段层级结构模型Tide 汰渍Tiffany 达芙妮Time 《时代周刊》time frame 时间框架/要求time pricing 时间定价time utility 时间效用Timex 天美时title 所有权Toshiba 东芝total cost 总成本total quality managemnt (TQM) 全面质量管理tough customer 苛刻的顾客Toyota Motor Corporation 丰田Toys R Us 美国着名玩具零售商tracking and monitoring 跟踪与监控trade mark 商标trade promotion 贸易促销trade selling 贸易销售trade/functional discounts 贸易/职能折扣trade-in allowance 以旧换新折让trading companies 贸易公司traditional stores 传统商店training 培训transactiional efficiency 交易效率transaction cost analysis (TCA) 交易成本分析transportation 运输trends 趋势turnkey construction contract 监督建筑契约turnover 人员流动two-sided presentations 双向信息陈述tying contracts 附带条件的合同Tylenol 泰诺营销英语词汇大全3 survival pricing 生存定价法sustainable competitive advantage 可持续的竞争优势sweepstakes 彩票抽奖switching cost 转换成本symbols 符号synergy 协同作用T tabulation 制表Taco Bell 塔可钟tangibility 有形性Tantem Computerstarget audience 目标受众target level of product quality 产品质量标准target or hurdle level 目标或难度水平target return price 目标回报价格targeting strategy 目标市场选择战略targeting 目标市场选择taste 口味/喜好team selling 团队销售technical selling 技术销售telecommunications industry 电讯产业telemarketing 电话销售television audience measurement 电视观众测量television home shopping 电视家庭购物territorial restrictions 地区限制territories 区域territory design and deployment 区域设计及部署territory inventory 地区存货test marketing 市场测试testing new product 测试新产品the American Association for Public Opinion Research 美国公共意见研究协会the Council of American Survey Research Organization 美国调查研究组织委员会the Fishbein Model 菲什宾模型the Marketing Research Association 营销研究协会theatre tests 现场测试营销英语词汇大全4statement of job qualifications 工作要求说明stock levels 库存水平stockless purchase arrangement 无存货采购计划store brands 零售商品牌straight commission compensation plan 纯佣金制薪酬方案straight rebuy 直接再购straight salary compensation plan 纯薪金制薪酬方案strategic alliances 战略联盟strategic business unit (SBU) 战略经营/业务单位strategic control 战略控制strategic fit 战略协调性strategic group 战略组strategic inertia 战略惯性strategic intent/objective 战略目标strategic marketing program 战略营销计划strategic pricing objectives 战略定价目标strategic withdrawal 战略撤退strategy constraints 战略影响因素strategy formulation and implementation 战略制定和实施strategy implementation 战略实施strategy reassessment 战略重估subculture 亚文化subfactor 次级因素substitute goods 替代品substitution threat 替代产品的威胁success rates 成功率Sumitomo 住友商事Sun Microsystems 太阳微系统supermarkets 超级市场supplementary media 辅助性广告媒体suppliers' bargaining power 供应商的讨价还价能力surrogate products 替代产品survey 调查营销英语词汇大全5 shopping goods 消费品short-term memory 短期记忆signal vehicle/carrier 信号载体simulated test marketing 模拟市场测试single-factor index 单因素指数法single-line mass-merchandiser stores 单一类型产品专营连锁店SKF 瑞典轴承公司skimming and early withdrawal 撇脂与尽早撤离战略skimming pricing 撇脂定价法sleepwalker/contented underachievers 梦游者/很容易满足的人slotting allowance 安置津贴social acceptability 社会可接受性social class 社会阶层social objectives 社会目标sociocultural environment 社会文化环境soft goods 非耐用品soft technology 软技术sole ownership entry strategy 独享所有权的进入战略Sony 索尼source credibility 信息来源的可信度source 广告信息来源sources of data 数据来源sources of new-product ideas 新产品创意来源speciality goods 特殊品speciality retailers 专营零售商speciality stores 专营商店specialization 专门化spokesperson 代言人Sprint 斯普林特Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) 标准工业分类代码standardization strategy 标准化战略standby positioning 备用定位staple goods 日常用品Starbucks 星巴克stars 明星类。

buyingandselling英语作文The art of buying and selling is one that has been honed over centuries as a fundamental aspect of human commerce and exchange. At its core buying and selling is the negotiation of value between two parties where one party seeks to acquire goods or services in exchange for payment while the other party seeks to profit from the transaction. This delicate balance of interests has driven the evolution of markets economies and shaped the way we conduct business on a global scale.The basic premise of buying and selling is relatively straightforward - one party has a good or service that they are willing to part with in exchange for compensation usually in the form of currency. The buyer, on the other hand, has a need or desire for that good or service and is willing to pay a certain price to obtain it. The challenge lies in determining the appropriate price that satisfies both the buyer's willingness to pay and the seller's need to profit.Historically this process of negotiation took place in physical marketplaces where buyers and sellers would congregate to barterand trade. The haggling and bargaining that occurred in these bustling hubs of commerce was an integral part of the buying and selling experience. Customers would carefully inspect goods examining quality craftsmanship and utility while sellers would tout the virtues of their wares in an attempt to command the highest possible price.With the advent of modern commerce and the rise of globalized trade networks the nature of buying and selling has evolved dramatically. No longer are transactions limited to face-to-face interactions in centralized market spaces. Today's buyers and sellers are able to connect across vast distances engaging in commercial exchanges through a variety of channels including brick-and-mortar stores e-commerce platforms and peer-to-peer online marketplaces.This shift towards a more digital landscape has introduced new complexities and considerations into the buying and selling dynamic. Online sellers must carefully curate their product listings optimize their marketing and ensure seamless logistics and customer service to remain competitive. Buyers on the other hand have access to a seemingly limitless array of options and must navigate a sea of reviews ratings and comparison tools to make informed purchasing decisions.Despite these technological advancements however the coreprinciples of buying and selling remain the same. Both parties are still seeking to maximize value and achieve a mutually beneficial outcome. The savvy buyer aims to obtain the best possible goods or services at the lowest price while the skilled seller strives to attract customers offer compelling value propositions and secure the highest profit margins.This delicate dance between buyers and sellers is what drives the engine of commerce and fuels economic growth on a global scale. Every day millions of transactions take place as individuals and businesses exchange money for the things they need and want. From the purchase of a morning coffee to the negotiation of a multi-million dollar merger the act of buying and selling is a fundamental part of the human experience.Of course the specific dynamics of these transactions can vary greatly depending on the nature of the goods or services involved as well as the broader economic and regulatory environment. In some cases buying and selling may be a straightforward transactional process with little room for negotiation. Think of purchasing a gallon of milk at the grocery store or renewing a subscription to a news publication.In other scenarios however the buying and selling process can be far more complex and nuanced. The sale of a home or the procurement of industrial equipment for example may involve extensive researchdue diligence and negotiations between multiple stakeholders. In these high-stakes situations both buyers and sellers must exercise greater care and strategic thinking to ensure they achieve their desired outcomes.Ultimately the art of buying and selling is one that requires a delicate balance of skill knowledge and emotional intelligence. Effective buyers must be savvy researchers adept negotiators and discerning consumers. Successful sellers on the other hand must be masterful marketers persuasive communicators and astute business operators.As the global marketplace continues to evolve the importance of these capabilities will only grow. In an increasingly crowded and competitive commercial landscape the ability to buy and sell with sophistication and savvy will be a key differentiator for both individuals and organizations. Those who can navigate the complexities of modern commerce with deftness and finesse will be poised to thrive while others may struggle to keep pace.In conclusion the act of buying and selling is a fundamental pillar of human economic activity. From the most basic consumer transactions to the highest-stakes business deals the interplay between buyers and sellers shapes the flow of commerce and fuels economic progress. As technology continues to transform the landscape of commerce the skills and strategies required to buy andsell effectively will only become more crucial. Those who master this art will be well-positioned to succeed in an increasingly dynamic and competitive global marketplace.。

反垄断怎么说英语作文As the global economy continues to grow, the issue of antitrust has become increasingly important. Antitrust is a legal framework designed to promote competition and prevent monopolies from dominating the market. In recent years, many countries have implemented antitrust laws to regulate the behavior of large corporations and protect consumers.The concept of antitrust can be traced back to the late 19th century, when the United States passed its first antitrust law, the Sherman Antitrust Act. This law was designed to prevent monopolies from controlling the market and to promote competition. Since then, many other countries have passed similar laws to protect their markets and consumers.The main goal of antitrust laws is to promote competition and prevent monopolies from dominating the market. A monopoly is a situation where one companycontrols the entire market, which can lead to higher pricesand reduced innovation. Antitrust laws aim to prevent this by regulating the behavior of large corporations and promoting competition.There are several ways that antitrust laws can be enforced. One way is through mergers and acquisitions. When two companies merge, it can create a monopoly in the market. Antitrust laws can be used to prevent this by requiring companies to divest certain assets or by blocking themerger altogether.Another way that antitrust laws can be enforced is through price fixing. Price fixing is when companiescollude to set prices, which can lead to higher prices for consumers. Antitrust laws can be used to prevent this by imposing fines or even criminal charges on companies that engage in price fixing.In addition to preventing monopolies and promoting competition, antitrust laws can also protect consumers. For example, antitrust laws can be used to prevent companies from engaging in false advertising or deceptive practices.They can also be used to ensure that consumers have access to a variety of products and services at reasonable prices.Overall, antitrust is an important legal framework that is designed to promote competition and prevent monopolies from dominating the market. As the global economy continues to grow, it is important for countries to implement and enforce antitrust laws to protect consumers and promote a healthy economy.。

Competition in Two-Sided MarketsMark ArmstrongDepartment of EconomicsUniversity College LondonAugust2002:revised May2005AbstractThere are many examples of markets involving two groups of agents who need to interact via“platforms”,and where one group’s bene…t from joining a platform dependson the number of agents from the other group who join the same platform.This paperpresents theoretical models for three variants of such markets:a monopoly platform;amodel of competing platforms where each agent must choose to join a single platform;and a model of“competing bottlenecks”,where one group wishes to join all platforms.The main determinants of equilibrium prices are(i)the relative sizes of the cross-groupexternalities,(ii)whether fees are levied on a lump-sum or per-transaction basis,and(iii)whether a group joins just one platform or joins all platforms.1Introduction and SummaryThere are many examples of markets where two or more groups of agents interact via inter-mediaries or“platforms”.Surplus is created—or perhaps destroyed in the case of negative externalities—when the groups interact.Of course,there are countless examples where…rms compete to deal with two or more groups.Any…rm is likely to do better if its products appeal to both men and women,for instance.However,in a set of interesting cases,cross-group network e¤ects are present,and the bene…t enjoyed by a member of one group depends upon how well the platform does in attracting custom from the other group.For instance,a heterosexual dating agency or nightclub can only do well if it succeeds in attracting business from both men and women.This paper is about such markets.An early version of this paper was presented at the ESEM meeting in Venice,August2002.I am grateful to the editor and two referees,to the audiences at many seminar presentations,to Simon Anderson,Carli Coetzee, Jacques Crémer,Xavier Vives and especially to Julian Wright for discussion,correction and information.1A brief list of other such markets includes:credit cards(for a given set of charges,a consumer is more likely to use a credit card which is accepted widely by retailers,while a retailer is more likely to accept a card which is carried by more consumers);television channels (where viewers generally prefer to watch a channel with fewer adverts,while an advertiser is prepared to pay more to place an advert on a channel with more viewers);and shopping malls (where a consumer is more likely to visit a mall with a greater range of retailers,while a retailer is willing to pay more to locate in a mall with a greater number of consumers passing through).See Rochet and Tirole(2003)for further examples of such markets.As this paper will argue in more detail,there are three main factors that determine the pattern of relative prices o¤ered to the two groups in equilibrium.Relative sizes of cross-group externalities:If a member of group1exerts a large positive externality on each member of group2,then group1will be targeted aggressively by platforms. In broad terms,and especially in competitive markets,it is group1’s bene…t to the other group that determines group1’s price,not how much group1bene…ts from the presence of group2 (see Proposition2below).In a nightclub,if men gain more from interacting with women than vice versa then we expect there to be a tendency for nightclubs to o¤er women lower entry fees than men.Unless they act to tip the industry to monopoly,positive cross-group network externalities act to intensify competition and reduce platform pro…ts—see expression(13)below.In order to be able to compete e¤ectively on one side of the market,a platform needs to perform well on the other side(and vice versa).This creates a downward pressure on the prices to both sides compared to the case where no cross-group network e¤ects exist.This implies that platforms would like to…nd ways to mitigate network e¤ects.One method of doing this is discussed next.Fixed fees or per-transaction charges:Platforms might charge for their services on a lump-sum basis,so that an agent’s payment does not explicitly depend on how well the platform performs on the other side of the market.Alternatively,if it is technologically feasible,the payment might be an explicit function of the platform’s performance on the other side.One example of this latter practice is where a TV channel or a newspaper makes its advertising charge an increasing function of the audience or readership it obtains.Similarly,a credit card network levies(most of)its charges on a per-transaction basis,while the bulk of a real estate agent’s fees are levied only in the event of a sale.The crucial di¤erence between the two charging bases is that cross-group externalities are weaker with per-transaction charges,since a fraction of the bene…t of interacting with an extra agent on the other side is eroded by the extra payment incurred.If an agent has to pay a platform only in the event of a successful interaction,then that agent does not need to worry about how well that platform will do in its dealings with the other side.That is to say,to attract one side of the market,it is not so important that the platform…rst gets the other side“on board”.Because network e¤ects are lessened with per-transactions charges,it is plausible that platform pro…ts are higher when this2form of charging is used.1(See Propositions3and5for illustrations of this e¤ect.)Finally,the distinction between the two forms of tari¤only matters when there are competing platforms. When there is a monopoly platform(see section3below),it makes no di¤erence to outcomes if tari¤s are levied on a lump-sum or per-transaction basis.Single-homing or multi-homing:When an agent chooses to use only one platform it has become common to say that the agent is“single-homing”.When an agent uses several platforms he is said to“multi-home”.It makes a signi…cant di¤erence to outcomes whether groups single-home or multi-home.In the broadest terms,there are three main cases to consider:(i)both groups single-home;(ii)one group single-homes while the other multi-homes,and(iii)both groups multi-home.If interacting with the other side is the primary reason for an agent to join a platform,then we might not expect case(iii)to be very common—if each member of group2joins all platforms,there is no need for any member of group1to join more than one platform—and so this con…guration is not analyzed in the paper.Con…guration(i)is discussed in section4.While the analysis of this case provides many useful insights about two-sided markets,it is hard to think of many markets that…t this con…guration precisely.By contrast,there are several important markets that look like con…guration(iii),and in section5these cases are termed“competitive bottlenecks”.Here,if it wishes to interact with an agent on the single-homing side,the multi-homing side has no choice except to deal with that agent’s chosen platform.Thus,platforms have monopoly power over providing access to their single-homing customers for the multi-homing side.This monopoly power naturally leads to high prices being charged to the multi-homing side,and there will be too few agents on this side being served from a social point of view(Proposition4).2By contrast,platforms do have to compete for the single-homing agents,and high pro…ts generated from the multi-homing side are to a large extent passed on to the single-homing side in the form of low prices(or even zero prices).Before embarking on this analysis in more detail,in the next section there is a selective literature review,followed in section3by an analysis of the monopoly platform case.1An exception to this occurs when the market tips to monopoly.In that case the incumbent’s pro…ts typically increase with the size of the network e¤ects since entrants…nd it hard to gain a toehold even when the incumbent sets high prices.This partly explains one conclusion of Caillaud and Jullien(2003),which is that equilibrium pro…ts typically rise when platforms cannot use transaction charges.2This tendency towards high prices for the multi-homing side is tempered somewhat when the single-homing side bene…ts from having many agents from the other side on the platform,for then high prices to the multi-homing side will drive away that side and thus disadvantage the platform when it tries to attract the single-homing side.However,this point is never su¢cient to undermine the basic result that the price charged to the multi-homing side is too high.32Related LiteratureI discuss some of the related literature later,as it becomes most relevant in the paper(especially in section5below).However,it is useful to discuss two pioneering papers up front.Caillaud and Jullien(2003)discuss the case of competing matchmakers,such as dating agencies,real estate agents,and internet“business-to-business”websites.3There is potentially a rich set of contracting possibilities.For instance,a platform might have a subscription charge in combination with a charge in the event of a successful match.In addition,Caillaud and Jullien allow platforms to set negative subscription charges,and to make their pro…t from taxing transactions on the platform.Caillaud and Jullien…rst examine the case where all agents must single-home.(I provide a parallel analysis in section4below.)In this case,there is essentially perfect competition,and agents have no intrinsic preference for one platform over another except insofar as one platform has more agents from the other side or charges lower prices.Therefore,the e¢cient outcome is for all agents to use the same platform. Caillaud and Jullien’s Proposition1shows that the only equilibria in this case involve one platform signing up all agents(as is e¢cient)and that platform making zero pro…ts.The equilibrium structure of prices involves negative subscription fees and maximal transactions charges,since this is the most pro…table way to prevent entry.Caillaud and Jullien go on to analyze the more complicated case where agents can multi-home.They analyze several possibilities,but the cases most relevant for this paper are what they term“mixed equilibria”(see their Propositions8and11).These correspond to the“competitive bottleneck”situations in this paper,and involve one side multi-homing and the other side single-homing.They…nd that the single-homing side is treated favourably(indeed,its price is necessarily no higher than its cost)while the multi-homing side has all its surplus extracted.I discuss the relationship between the two approaches in more detail in section5.5below.The second closely related paper is Rochet and Tirole(2003).The‡avour of their analysis can be understood in the context of the credit card market(although the analysis applies more widely).On one side of the market are consumers and on the other side is the set of retailers,and facilitating the interaction between these two groups are two competing credit card networks.For much of their analysis,the credit card platforms levy charges purely on a per-transaction basis,and there are no lump-sum fees for either side.Suppose that one credit card o¤ers a lower transaction fee to retailers than its rival.A retailer choosing between accepting just the cheaper card or accepting both cards faces a trade-o¤.If it accepts just the cheaper card then its consumers have a stark choice between paying by this card or not using a card at all.Alternatively,if it accepts both cards then(i)more consumers will choose to pay by some card but(ii)fewer consumers will use the retailer’s preferred lower-cost card.If a credit card reduces its charge to retailers relative to its rival,this will“steer”some retailers which previously accepted both cards to accept only the lower-cost card.In a symmetric equilibrium,all retailers accept both credit cards(or neither),while consumers always use 3See also van Raalte and Webers(1998).4their preferred credit card.The share of the charges that are borne by the two sides dependson how closely consumers view the two cards as substitutes.If few consumers switch cardsin response to a price cut on their side,then consumers should pay a large share of the totaltransaction charge;if consumers view the cards as close substitutes,then retailers will bearmost of the charges in equilibrium.Rochet and Tirole also consider the case where there are…xed fees as well as per-transaction fees,under the assumption that consumers use a singlecard.This is essentially the same model as the competitive bottleneck model in this paper,and I discuss this part of their paper in more detail in section5.5below.There are a number of modelling di¤erences between the current paper and Rochet andTirole(2003)which concern the speci…cation of agents’utility,the structure of platforms’fees,and the structure of platforms’costs.4In both papers agent j has gross utility from usingplatform i of the formu i j= i j n i+ i j:Here n i is the number of agents from the other side who are present on the platform, i j is the bene…t that agent j enjoys from each agent on the other side,and i j is the…xed bene…t the agent obtains from using that platform.Rochet and Tirole assume that i j does not dependon i or j(and can be set equal to zero),but that i j varies both with agent j and platformi.In section3and4of the current paper,by contrast,I assume that i j does not depend on i or j but only on which side of the market the agent is on,while i j depends on the agentand on the platform.(In section5I suppose that the interaction term for one side does vary.)The decision whether to make agents’heterogeneity to do with the interaction term or the…xed e¤ect has major implications for the structure of prices to the two sides in equilibrium.For instance,with a monopoly platform the formulas for pro…t-maximizing prices look verydi¤erent in the two papers.Moreover,when i j depends on the platform i,an agent caresabout on which platform the transaction takes place(if there is a choice):this e¤ect plays amajor role in Rochet and Tirole’s analysis but is absent in the present paper.5Turning to the structure of the platforms’fees,for the most part Rochet and Tirole assumethat agents pay a per-transaction fee for each agent on the platform from the other side.Ifthis fee is denoted i then agent j’s net utility on platform i is u i j=( i j i)n i(when is set equal to zero).This con…rms the discussion in section1above that per-transactionscharges act to reduce the size of network e¤ects.In the monopoly platform case,an agent’sincentive to join the platform does not depend on the platform’s performance on the otherside,and she will join if and only if i j i.The present paper,especially in section4, 4The assumptions in Caillaud and Jullien(2003)to do with utility and costs are closer to the current paper than to Rochet and Tirole.Caillaud and Jullien do not have any intrinsic product di¤erentiation between the platforms.However,there is a bene…t to join two platforms rather than one since they assume that there is a better chance of a match between buyers and sellers when two platforms are involved.5A recent paper that encompasses these two approaches with a monopoly platform is Rochet and Tirole (2004),where simultaneous heterogeneity in both and is allowed.However,a full analysis of this case is technically challenging in the case of competing platforms.5assumes that platform charges are levied as a lump-sum fee,p i say,in which case the agent’s net utility is u i j= n i+ i j p i.The…nal modelling di¤erence between the two papers is with the speci…cation of costs:Rochet and Tirole assume mainly that a platform’s costs are incurred on a per-transaction basis,so that if a platform has n1group1agents and n2group 2agents its total cost is cn1n2for some per-transaction cost c.In the current paper costs are often modelled as being incurred when agents join a network,so that a platform’s total cost is f1n1+f2n2for some per-agent costs f1and f2.Which assumptions concerning tari¤s and costs best re‡ects reality depends on the context.Rochet and Tirole’s model is well suited to the credit card context,for instance,whereas the assumptions in the current paper are intended to better re‡ect markets such as nightclubs,shopping malls and newspapers.3Model I:A Monopoly PlatformThis section presents the analysis for a monopoly platform.This framework does not apply to most of the examples of two-sided markets that come to mind,although there are a few applications.For instance,yellow pages directories are often a monopoly of the incumbent telephone company,shopping malls or nightclubs are sometimes far enough away from others that the monopoly paradigm might be appropriate,and sometimes there is only one newspaper or magazine in the relevant market.Suppose there are two groups of agents,denoted1and2.A member of one group cares about the number of the other group who use the platform.(For simplicity,I ignore the possibility that agents care also about the number of the same group who join the platform.) Suppose that the utility of an agent is determined in the following way:if the platform attracts n1and n2members of the two groups,the utilities of a group1and a group2agent are respectivelyu1= 1n2 p1;u2= 2n1 p2;(1) where p1and p2are the platform’s prices to the two groups.The parameter 1measures the bene…t that a group1agent enjoys from interacting with each group2agent,and 2measures the bene…t a group2agent obtains from each group1agent.Expression(1)describes how utility is determined as a function of the numbers of agents who participate.To close the demand model I specify the numbers who participate as a function of the utilities:if the utilities o¤ered to the two groups are u1and u2,suppose that the numbers of each group who join the platform aren1= 1(u1);n2= 2(u2)for some increasing functions 1and 2.Turning to the cost side,suppose that the platform incurs a per-agent cost f1for serving group1and per-agent cost f2for group2.Therefore,the…rm’s pro…t is =n1(p1 f1)+ n2(p2 f2).If we consider the platform to be o¤ering utilities f u1;u2g rather than prices f p1;p2g,then the implicit price for group1is p1= 1n2 u1(and similarly for group2).6Therefore,expressed in terms of utilities,the platform’s pro…t is(u1;u2)=[ 1 2(u2) u1 f1] 1(u1)+[ 2 1(u1) u2 f2] 2(u2):(2) Let the aggregate consumer surplus of group1be v1(u1),where v1satis…es the envelope condition v01(u1) 1(u1),and similarly for group2.Then total welfare,as measured by the unweighted sum of pro…t and consumer surplus,isw= (u1;u2)+v1(u1)+v2(u2):It is easily veri…ed that the…rst-best welfare maximizing outcome involves utilities satisfying:u1=( 1+ 2)n2 f1;u2=( 1+ 2)n1 f2:From expression(1)the socially optimal prices satisfyp1=f1 2n2;p2=f2 1n1:As one would expect,the optimal price for group1,say,equals the cost of supplying service to a type1agent adjusted downwards by the external bene…t that an extra group1agent brings to the group2agents on the platform.(There are n2group2agents on the platform, and each one bene…ts by 2when an extra group1agent joins.)In particular,prices should ideally be below cost if 1; 2>0.From expression(2),the pro…t-maximizing prices satisfyp1=f1 2n2+ 1(u1)01(u1);p2=f2 1n1+ 2(u2)02(u2):(3)Thus,the pro…t-maximizing price for group1,say,is equal to the cost of providing service(f1), adjusted downwards by the external bene…t( 2n2),and adjusted upwards by a factor related to the elasticity of the group’s participation.The pro…t-maximizing prices can be obtained in the more familiar form of Lerner indices and elasticities,as recorded in the following result: Proposition1Write1(p1j n2)=p1 01( 1n2 p1)1( 1n2 p1); 2(p2j n1)=p2 02( 2n1 p2) 2( 2n1 p2)for a group’s price elasticity of demand for a given level of participation by the other group. Then the pro…t-maximizing pair of prices satisfyp1 (f1 2n2)p1=11(p1j n2);p2 (f2 1n1)p2=12(p2j n1):(4) 7It is possible that the pro…t-maximizing outcome might involve group1,say,being o¤ereda subsidised service,i.e.,p1<f1.From(4),this happens if the group’s elasticity of demandis high and/or if the external bene…t enjoyed by group2is large.Indeed,the subsidy mightbe so large that the resulting price is negative(or zero,if negative prices are not feasible).This analysis applies,in a stylized way,to a market with a monopoly yellow page directory.Such directories typically are given to telephone subscribers for free,and pro…ts are made fromcharges to advertisers.The analysis might also apply to software markets where one type ofsoftware is required to create…les in a certain format and another type of software is requiredto read such…les.(For the analysis to apply accurately,though,there needs to be two disjointgroups of agents:those who wish to read…les and those who wish to create…les.It does notreadily apply when most people wish to perform both tasks.)4Model II:Two-Sided Single-HomingThis model involves competing platforms,but assumes that,for exogenous reasons,each agentfrom either group chooses to join a single platform.4.1Basic ModelThe model extends the previous monopoly model in a natural way.There are two groups ofagents,1and2,and there are two platforms,A and B,which enable the two groups to interact.Groups1and2obtain the respective utilities f u i1;u i2g from platform i.These utilities f u i1;u i2g are determined in a similar manner to the monopoly model expressed in(1):if platform iattracts n i1and n i2members of the two groups,the utilities on this platform areu i1= 1n i2 p i1;u i2= 2n i1 p i2;(5) where f p i1;p i2g are the respective prices charged by the platform to the two groups.When group1is o¤ered a choice of utilities u A1and u B1from the two platforms,and group2is o¤ered the choice u A2and u B2,suppose that the number of each group who go to platformi is given by the Hotelling speci…cation:n i1=12+u i1 u j12t1;n i2=12+u i2 u j22t2:(6)Here,agents in a group are assumed to be uniformly located along a unit interval with the two platforms located at the two end-points,and t1,t2>0are the product di¤erentiation(or transport cost)parameters for the two groups that determine the competitiveness of the two markets.8Putting(6)together with(5),and using the fact that n j1=1 n i1,gives the following implicit expressions for market shares:n i1=12+1(2n i2 1) (p i1 p j1)2t1;n i2=12+2(2n i1 1) (p i2 p j2)2t2:(7)Expressions(7)show that,keeping its group2price…xed,an extra group1agent on a platformattracts a further 2t2group2agents to that platform.Suppose that the network externality parameters f 1; 2g are small compared to the dif-ferentiation parameters f t1;t2g so that I can focus on market-sharing equilibria.(If network e¤ects were large compared to brand preferences then there could only be equilibria where one platform corners both sides of the market.)It turns out that the necessary and su¢cient condition for a market-sharing equilibrium to exist is the following:4t1t2>( 1+ 2)2(8) and this inequality is assumed to hold in the following analysis.Suppose that platforms A and B o¤er the respective price pairs(p A1;p A2)and(p B1;p B2). Solving the simultaneous equations(7)implies that market shares are determined by the four prices as:n i1=12+121(p j2 p i2)+t2(p j1 p i1)t1t2 1 2;n i2=12+122(p j1 p i1)+t1(p j2 p i2)t1t2 1 2:(9)(Assumption(8)implies that the above denominators t1t2 1 2are positive.)Thus,assuming 1; 2>0,a platform’s market share for one group is decreasing in its price o¤ered to the other group.As with the monopoly model,suppose that each platform has a per-agent cost f1for serving group1and f2for serving group2.Therefore,pro…ts for platform i are(p i1 f1)"12+12 1(p j2 p i2)+t2(p j1 p i1)t1t2 1 2#+(p i2 f2)"12+12 2(p j1 p i1)+t1(p j2 p i2)t1t2 1 2#:This expression is quadratic in platform i’s prices,and is concave in these prices if and only if assumption(8)holds.Therefore,platform i’s best response to j’s prices is characterized by the…rst-order conditions.Given assumption(8),one can check there are no asymmetric equilibria.For the case of a symmetric equilibrium where each platform o¤ers the same price pair(p1;p2),the…rst-order conditions for equilibrium prices arep1=f1+t1 2t2( 1+p2 f2);p2=f2+t2 1t1( 2+p1 f1):(10)Expressions(10)can be interpreted in the following manner.First,note that in a Hotelling model without network e¤ects,the equilibrium price for group1would be p1=f1+t1.In9this two-sided setting the price is adjusted downwards by the factor 2t2( 1+p2 f2).Thisadjustment factor can be decomposed into two parts.The term( 1+p2 f2)represents the “external”bene…t to a platform of having an additional group2agent.To see this,note…rst that the platform makes pro…t(p2 f2)from each extra group2agent.Second, 1measures the extra revenue the platform can extract from its group1agents(without losing market share)when it has an extra group2agent.6Thus( 1+p2 f2)indeed represents the external bene…t to a platform of attracting the marginal group2agent.Finally,as shown in expression(7),a platform attracts 2t2extra group2agents when it has an extra group1agent.In sum,the adjustment factor 22( 1+p2 f2)measures the external bene…t to the platform fromattracting an extra group1agent;in other words,it measures the opportunity cost of raising the group1price enough to cause one group1agent to leave.I summarize this discussion by an annotated version of formula(10):p1=f1|{z}cost of service+t1|{z}market power factor 2t2|{z}extra group2agents( 1+p2 f2)|{z}pro…t from each extra group2agent(11)Finally,solving the simultaneous equations(10)implies that p1=f1+t1 2and p2= f2+t2 1:This discussion is summarized as:Proposition2Suppose that assumption(8)holds.Then the model with two-sided single-homing has a unique equilibrium which is symmetric.Equilibrium prices for group1and group2are given byp1=f1+t1 2;p2=f2+t2 1:(12) Thus,a platform will target one group more aggressively than the other if that group is (i)on the more competitive side of the market and/or(ii)causes larger bene…ts to the other group than vice versa.7While expressions(12)are certainly“simple”,they are not intuitive,and this is why I focussed the discussion on(10).The fact that,say,group1’s price does not depend on its own externality parameter 1is surely an artifact of the Hotelling speci…cation for consumer demand.In particular,the fact that the total size of each group is…xed,so that when platforms set low prices they only steal business from the rival rather than expand the overall 6An extra group2agent means that the utility of each group1agent on the platform increases by 1,while the utility of each group1agent on the rival platform falls by 1.Therefore,the relative utility for group1 agents being on the platform increases by2 1and each of the agents can bear a price increase equal to this. Since in equilibrium a platform has half the group1agents,the extra revenue it can extract from these agents is 1,as claimed.7It is possible given our assumptions that one price in the above expression is negative.This happens if that side of the market involves a low cost,is competitive,or causes a large external bene…t to the other side. In many cases it is not realistic to suppose that negative prices are feasible,in which case the analysis needs to be adapted explicitly to incorporate the non-negativity constraints—see Armstrong and Wright(2004)for this analysis.10。

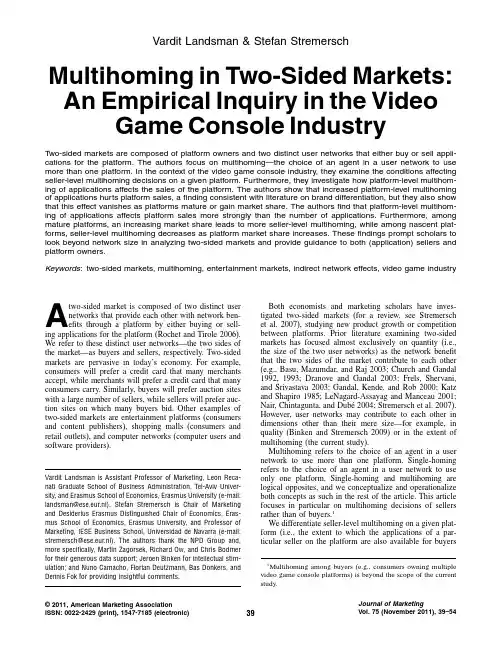

Vardit Landsman&Stefan Stremersch Multihoming in Two-Sided Markets: An Empirical Inquiry in the Video Game Console IndustryTwo-sided markets are composed of platform owners and two distinct user networks that either buy or sell appli-cations for the platform.The authors focus on multihoming—the choice of an agent in a user network to use more than one platform.In the context of the video game console industry,they examine the conditions affecting seller-level multihoming decisions on a given platform.Furthermore,they investigate how platform-level multihom-ing of applications affects the sales of the platform.The authors show that increased platform-level multihoming of applications hurts platform sales,afinding consistent with literature on brand differentiation,but they also show that this effect vanishes as platforms mature or gain market share.The authorsfind that platform-level multihom-ing of applications affects platform sales more strongly than the number of applications.Furthermore,among mature platforms,an increasing market share leads to more seller-level multihoming,while among nascent plat-forms,seller-level multihoming decreases as platform market share increases.Thesefindings prompt scholars to look beyond network size in analyzing two-sided markets and provide guidance to both(application)sellers and platform owners.Keywords:two-sided markets,multihoming,entertainment markets,indirect network effects,video game industryA two-sided market is composed of two distinct usernetworks that provide each other with network ben-efits through a platform by either buying or sell-ing applications for the platform(Rochet and Tirole2006). We refer to these distinct user networks—the two sides of the market—as buyers and sellers,respectively.Two-sided markets are pervasive in today’s economy.For example, consumers will prefer a credit card that many merchants accept,while merchants will prefer a credit card that many consumers carry.Similarly,buyers will prefer auction sites with a large number of sellers,while sellers will prefer auc-tion sites on which many buyers bid.Other examples of two-sided markets are entertainment platforms(consumers and content publishers),shopping malls(consumers and retail outlets),and computer networks(computer users and software providers).Vardit Landsman is Assistant Professor of Marketing,Leon Reca-nati Graduate School of Business Administration,Tel-Aviv Univer-sity,and Erasmus School of Economics,Erasmus University(e-mail: landsman@ese.eur.nl).Stefan Stremersch is Chair of Marketing and Desiderius Erasmus Distinguished Chair of Economics,Eras-mus School of Economics,Erasmus University,and Professor of Marketing,IESE Business School,Universidad de Navarra(e-mail: stremersch@ese.eur.nl).The authors thank the NPD Group and, more specifically,Martin Zagorsek,Richard Ow,and Chris Bodmer for their generous data support;Jeroen Binken for intellectual stim-ulation;and Nuno Camacho,Florian Deutzmann,Bas Donkers,and Dennis Fok for providing insightful comments.Both economists and marketing scholars have inves-tigated two-sided markets(for a review,see Stremersch et al.2007),studying new product growth or competition between platforms.Prior literature examining two-sided markets has focused almost exclusively on quantity(i.e., the size of the two user networks)as the network benefit that the two sides of the market contribute to each other (e.g.,Basu,Mazumdar,and Raj2003;Church and Gandal 1992,1993;Dranove and Gandal2003;Frels,Shervani, and Srivastava2003;Gandal,Kende,and Rob2000;Katz and Shapiro1985;LeNagard-Assayag and Manceau2001; Nair,Chintagunta,and Dubé2004;Stremersch et al.2007). However,user networks may contribute to each other in dimensions other than their mere size—for example,in quality(Binken and Stremersch2009)or in the extent of multihoming(the current study).Multihoming refers to the choice of an agent in a user network to use more than one platform.Single-homing refers to the choice of an agent in a user network to use only one platform.Single-homing and multihoming are logical opposites,and we conceptualize and operationalize both concepts as such in the rest of the article.This article focuses in particular on multihoming decisions of sellers rather than of buyers.1We differentiate seller-level multihoming on a given plat-form(i.e.,the extent to which the applications of a par-ticular seller on the platform are also available for buyers 1Multihoming among buyers(e.g.,consumers owning multiple video game console platforms)is beyond the scope of the current study.©2011,American Marketing AssociationISSN:0022-2429(print),1547-7185(electronic)39Journal of MarketingVol.75(November2011),39–54of competing platforms)from platform-level multihoming (i.e.,the extent to which applications on a particular plat-form are also available for buyers of a competing platform). Thus,platform-level multihoming represents the aggrega-tion of seller-level multihoming over all sellers providing applications for a particular platform.A seller can multi-home many(few)of its applications for a given platform, which in our terminology reflects a high(low)degree of seller-level multihoming.At the platform level,many(few) of the applications available for a platform across all sell-ers may be multihomed,which in our terminology reflects a high(low)degree of platform-level multihoming. Theoretical models have suggested that the extent to which applications on a particular platform are multi-homed(platform-level multihoming)constitutes an impor-tant driver of the outcome of platform competition (Armstrong2006;Armstrong and Wright2007;Caillaud and Jullien2003;Hermalin and Katz2006;Rochet and Tirole2006).The special relevance of multihoming to plat-form owners(Shapiro1999)stems from the fact that the differentiation of a platform partially lies with the differ-entiation of the characteristics of its user network(s)from the characteristics of the user network(s)of competing plat-forms,beyond the differentiation between the other charac-teristics(e.g.,hardware)of the platforms.Seller-level multihoming decisions are important deci-sions for sellers in two-sided markets.On the one hand,a seller that single-homes on a given platform forgoes poten-tial revenues from the buyers of competing platforms.On the other hand,single-homing sellers may have lower costs (e.g.,they avoid the cost of adapting their applications to multiple platforms)or be paid exclusivity fees by owners of platforms on which they single-home.Multihoming decisions are of great importance tofirms in many contexts.For example,researchers credit the single-homing decision by several movie studios(e.g., Warner Brothers)as an important factor in the platform bat-tle between Toshiba’s HD DVD and Sony’s Blu-ray(Barnes 2007;Edwards and Grover2008).Sony is also reported to have paid a substantial amount to movie studios to pre-vent attractive movies on Blu-ray from being multihomed to HD DVD.The video game console market—the context of the current study—is another market in which sellers’multi-homing decisions may significantly affect their profits.For example,Take-Two’s Rockstar Games unit was reported to have received an estimated$50million from Microsoft to create two episodes of Grand Theft Auto IV:The Lost and Damned and single-home them for Microsoft Xbox360. However,by single-homing,Take-Two’s Rockstar Games unit missed the revenues that these games might have gen-erated,especially from Sony PlayStation3users.Despite the high relevance of multihoming in many industries and a stream of recent analytical research(mostly in economics),little empirical research on multihoming exists(for exceptions,which we in turn extend,see Binken and Stremersch2009;Corts and Lederman2009;Rys-man2004).More precisely,we study two research ques-tions,which have remained largely unaddressed by prior (empirical)literature.First,we investigate what conditions affect seller-level multihoming decisions on a given plat-form(in our case,multihoming decisions of game publish-ers).Second,we study whether and under what conditions platform-level multihoming affects the sales of the platform (in our case,sales of video game consoles),explicitly con-trolling for the number of applications sold for the platform. We focus on the age and market share of the platform as conditions that may influence the extent of seller-level multihoming on the platform and the effect of platform-level multihoming on platform sales.Both age and market share of a platform significantly affect the uncertainty that consumers face in their platform adoption decision.Uncer-tainty plays a dominant role in any new technology adop-tion,but does so especially in two-sided markets because the future adoption by the seller network affects the future utility of a platform for consumers.The uncertainty regard-ing a platform decreases with age and market share,which in turn affects the extent to which the platform needs a clearly differentiated positioning to be successful.Thus,in short,nascent and low-market-share platforms may have a greater need for a differentiated network of sellers than mature and high-market-share platforms.Our empiricalfindings are as follows:Wefind that the (negative)effect of platform-level multihoming on platform sales is larger than the(positive)effect of the number of applications on platform sales.We alsofind that this neg-ative effect of multihoming is prominent for nascent plat-forms and for platforms with a small market share but it fades as platforms mature and gain market share.These findings have implications for sellers and platform owners. They may provide sellers with a better understanding of the conditions under which the platform owner may be willing to pay more or less for single-homed applications.Platform owners can also gain understanding of the conditions in which it benefits them to encourage or discourage single-homed applications for their platforms.Thesefindings may also affect the future behavior of industry observers(e.g., in the reports they publish)and academic scholars(e.g.,in the models they develop)because they force both observers and academics to move away from the logic of network size to the logic of multihoming.We alsofind that a platform’s age and market share, among other factors,drive the extent of seller-level multi-homing on that platform.On the one hand,the larger the market share of a mature platform among buyers,the more of its applications will be multihomed.On the other hand, the larger the market share of a nascent platform,the fewer of its applications will be multihomed.We organize the remainder of this article as follows:In the next section,we review the literature on multihoming. Then,we develop hypotheses for the effects of multihom-ing on platform sales and for the determinants of multihom-ing.The fourth section presents the data we use to test the developed theory.We develop our model in thefifth section and present the estimation procedure in the sixth section. We present the estimation results in the seventh section.We conclude with a discussion of the implications and limita-tions of our research.Prior Literature on Multihoming We can distinguish two types of prior analytical models on multihoming in two-sided markets.Thefirst type examines what the equilibrium outcome is if a multihoming option exists for a user group,without the(potential)existence of40/Journal of Marketing,November2011exclusive contracts(Armstrong2006;Caillaud and Jullien 2003;Choi2007;Doganoglu and Wright2006;Rochet and Tirole2003,2006).Most relevant to our own inquiry is the theoretical model Choi(2007)proposes,which con-siders the level of suitability of a seller’s applications for a specific platform as a determinant of that seller’s deci-sion to single-home its applications on that platform.In our theoretical framework,we also adopt this notion of seller–platformfit as one of the factors influencing multihoming decisions.We theorize that thefit between a seller and a given platform is conveyed through the sales success of the sellers’applications among the buyers of the platform.2A second set of models examines the equilibrium out-come if a platform owner offers an option of an exclusive contract—a contract under which agents in a user network commit to single-home on a given platform—in a con-text in which the multihoming option exists,or in specific settings of platforms’competitive strength and life-cycle stages(Armstrong and Wright2007;Balto1999;Carrillo and Tan2006;Doganoglu and Wright2010;Mantena, Sankaranarayanan,and Viswanathan2007;Shapiro1999). Such exclusive contracts are relevant to market outcomes only when sellers would otherwise opt to multihome or to single-home on a competing platform.Scholars in this area debate the conditions under which the employment of such exclusive contracts has negative welfare consequences. Armstrong and Wright(2007)find that exclusive deals may actually promote a superior market outcome for both buy-ers and sellers under certain market conditions.Doganoglu and Wright(2010)find that exclusive deals are inefficient when offered by incumbentfirms as a tool to dominate a market in the face of entry,and the seller network is the primary beneficiary of such deals.Note that in our theoretical framework,as presented in the next section,we do not specifically distinguish differ-ent motivations for inducing single-homing through exclu-sive contracts,nor do we determine the beneficiaries of such actions.However,we consider the age and the mar-ket share of the platform as determinants of multihoming decisions and,in doing so,aim to generalize the condi-tions under which we can expect higher levels of multi-homing.In this respect,a study of special relevance to our present inquiry is that of Mantena,Sankaranarayanan,and Viswanathan(2007).Their analytical model examines the conditions under which single-homing can be observed and the impact of single-homing on industry outcomes,taking into account the typical high level of uncertainty buyers in two-sided markets face.Mantena,Sankaranarayanan,and Viswanathan’s work applies to the context of high technol-ogy and media markets,which share many features with our empirical context.Empirical studies relevant to our context are few in number and different in nature from our current inquiry. Rysman(2004)documents network benefits between buy-ers(consumers)and sellers(advertisers)of a platform (yellow pages).For simplicity reasons,he assumes that buyers single-home and sellers choose platforms only on the basis of the number of buyers of the platform.Corts 2In the section on robustness,we also consider an alternative measure of seller-platformfit that is based on application quality rather than application sales.and Lederman(2009)study the influence of platforms’installed base of buyers on the number of single-homed and multihomed applications published.They also study the influence of the number of applications on own and competing platform sales,which allows them to be thefirst to provide evidence of network benefits gained not only for a given platform but also across competing platforms. Binken and Stremersch(2009)are thefirst to show that superstar applications—applications of very high quality (i.e.,a quality rating≥90/100)that command a dispropor-tionately large payoff in application sales—affect platform sales beyond the effect of the total number of applications. Theyfind that the effects of single-homed and multihomed superstar applications on platform sales are similar. Using new metrics for seller-level and platform-level multihoming,we extend this empirical literature by (1)quantifying the effect of platform-level multihoming on platform sales across the entire collection of applica-tions and over all competing platforms in a direct manner, (2)theorizing and empirically documenting the moderat-ing role of market share and age of the platform on the relationship between platform-level multihoming and plat-form sales,and(3)theorizing and empirically documenting contrary effects of platform market share on seller-level multihoming,depending on the age of the platform.Theory DevelopmentIn this section,wefirst derive our theoretical expectations on the effect of platform-level multihoming on sales of the platform and the conditions that may influence this effect.In terms of conditions,we focus on the age and market share of the platform,because an increase in either may significantly lower the uncertainty that consumers face in their platform adoption decision.We expect that the greater this uncertainty,the more a platform needs a clearly differentiated positioning to be commercially successful. Then,we explore the effect of such conditions on seller-level multihoming on a given platform.Figure1provides a graphic overview of our conceptual framework and the hypotheses we posit.For the derivation of our hypotheses, we build on theories on differentiation and uncertainty in two-sided markets.The Influence of Platform-Level Multihoming on Platform SalesWhen a platform’s applications are multihomed on other platforms,the platform may not be able to differentiate itself through the applications of its network of sellers. Differentiation provides brands with greater resistance to competitive attacks(e.g.,Aaker1991;Carpenter,Glazer, and Nakamoto1994).Thus,in two-sided markets,in which buyers and sellers endow each other with network ben-efits,a platform for which few applications are multi-homed can achieve greater differentiation than a platform for which many applications are multihomed(Mantena, Sankaranarayanan,and Viswanathan2007).For example, the video game Tetris,which was single-homed on Game Boy,is credited for much of the Game Boy’s success(Allen 2003;Rowe1999).Platforms might not all be equally affected by a lack of differentiation from multihoming.We expect that nascentMultihoming in Two-Sided Markets/41FIGURE1Conceptual Frameworka Multihoming across all the seller’s applications for the platform.platforms(i.e.,platforms that have been introduced only recently)are more vulnerable to multihoming of their appli-cations than mature platforms.The level of buyers’uncer-tainty on a nascent platform is high initially,after which uncertainty fades as the platform matures.Under the high uncertainty characterizing nascent platforms,buyers’pref-erences for a platform can more easily tip in favor of a platform for which few of its applications are multihomed than a platform for which many of its applications are multihomed,keeping the number of applications constant (Mantena,Sankaranarayanan,and Viswanathan2007).As platforms mature,buyers’expectations about the ultimate success of the platform become more certain(Schilling 2002),and the need for differentiation through a platform’s applications decreases.We hypothesize the following: H1:There is a negative relationship between platform-level multihoming of applications and platform sales for nascentplatforms,which fades as platforms mature.Two-sided markets are known to“tip”in favor of the largest-share platform(Arthur1989).As a platform increas-ingly beats other platforms in terms of market share,other platform attributes(e.g.,the extent of platform-level multi-homing)become less important in buyers’platform choice.A large market share of a platform provides a clearer signal of the superior value the platform offers for buyers than attributes that are more difficult for a consumer to measure (Schilling1999),such as the number of applications for the platform that are multihomed.The important role of platform market share as a sig-nal for superior value alsofits priorfindings in differen-tiation theory.Carpenter and Nakamoto(1989)argue that greater similarity between brands hurts only the nondomi-nant brand and not the dominant brand.In the context of pioneering advantages,they attribute an overall perceptual distinctiveness to dominant brands that allows them to over-shadow similar,but smaller,competitors.Feinberg,Kahn, and McAlister(1992),who study variety seeking,alsofind that when consumer preferences remain constant,sharing more features with competing brands hurts small brands but does not hurt dominant brands.As we argued previ-ously,platform-level multihoming may lead to a lack of differentiation,which,according to this logic,would hurt dominant brands less than nondominant brands.Therefore, we hypothesize the following:H2:There is a negative relationship between platform-level multihoming of applications and platform sales for plat-forms with a small market share,which fades as platformsgain market share.In our empirical tests of the preceding hypotheses,we control for several other variables that may affect platform sales in addition to platform age and market share.3First, we control for the number of applications that are avail-able for the platform,which we expect to positively affect platform sales(Church and Gandal1993;Katz and Shapiro 1994).Second,we control for the number of platforms that compete with one petition may increase platform sales because it may benefit the growth of the industry(Agarwal and Bayus2002),or it may decrease 3Note that in the application context of this study,the correlation between market share and platform sales is low(.33)because of the high category sales growth over time.42/Journal of Marketing,November2011platform sales through platform switching (Carpenter and Lehmann 1985).Third,we control for the price of the plat-form,which we expect to negatively affect platform sales.Fourth,we include the number of superstar releases for the platform (Binken and Stremersch 2009).In addition,we control for seasonality in sales by including a December dummy,for inertia in sales by including the platform’s sales in the previous period,and for other time-invariant plat-form features by including platform dummies.In our case,such platform features can be technical attributes such as data width,clock speed,memory,the type of controller,the media device (e.g.,CD-ROM,DVD,Blu-ray),or the pos-sibility to access the Internet,as well as other aspects such as the brand name and credibility of the platform owner.Determinants of Seller-Level MultihomingSeller-level multihoming is the outcome of the decision of platform owners to provide incentives to lower the level of seller-level multihoming and the decision of sellers on the level of seller-level multihoming,given such incentives.We theorize on the effects of age and market share of the platform and the seller–platform fit on the platform owner and seller decisions,and,in turn,on the level of seller-level multihoming.As H 1predicts,when a platform is mature,the platform owner has little need to offer sellers incentives to discour-age them from multihoming.Owners of nascent platforms may have a greater need to offer sellers such incentives.These arguments may explain the increase in multihoming over the life cycle of a platform (as illustrated in Figure 2).FIGURE 2Multihoming for All Platforms (July 1995–April 2008)0 .1 .2 .3.4 .5.6ii.7.8 .9J a n -08A u g -07M a r -07O c t -06M a y -06D e c -05J u l -05F e b -05S e p -04A p r -04N o v -03J u n -03J a n -03A u g -02M a r -02O c t -01M a y -01D e c -00J u l -00F e b -00S e p -99A p r -99N o v -98J u n -98J a n -98A u g -97M a r -97O c t -96M a y -96D e c -95J u l -95Beyond this direct effect,platform age may also inter-act with the market share of the platform.The owner of a mature platform with a large market share will have an even lower need to offer incentives to discourage sellers from multihoming than the owner of a mature platform with a small market share,because high-share platforms are hurt less by seller-level multihoming than low-share plat-forms.Therefore,as the market share of a mature platform increases,we expect the platform owner to offer sellers fewer incentives that discourage them from multihoming.At the same time,if a small-share,mature platform offers such incentives,sellers may still accept them,despite the low market share of the platform because such platforms may still represent sizeable buyer networks in absolute numbers (Mantena,Sankaranarayanan,and Viswanathan 2007).In summary,the incidence of seller-level multihoming among mature platforms likely increases with market share.For nascent platforms,the opposite is true.In the early stage of the life cycle of a new platform in a two-sided market,buyers are still largely undecided,and the user base is still small (see Mantena,Sankaranarayanan,and Viswanathan 2007;Schilling 2002;Stremersch et al.2007).Nascent platforms are therefore likely to offer sellers incen-tives to discourage them from multihoming because the lack of differentiation caused by multihoming may substan-tially hurt such platforms.Sellers will more easily accept such incentives from owners of platforms with a greater market share because their higher market share serves as a signal of superior value to sellers.Therefore,we expect to find a lower incidence of seller-level multihoming forMultihoming in Two-Sided Markets /43nascent platforms with greater market shares(compared with nascent platforms with lower market shares).We hypothesize the following:H3:The relationship between the market share of a platform among buyers and the extent of seller-level multihomingof applications for that platform is(a)negative for nascentplatforms and(b)positive for mature platforms. Next,we theorize that a betterfit between a seller’s applications and the characteristics of the platform or of the platform’s buyers’network(Choi2007)increases the platform owner’s inclination to make high payments to the seller to reduce the degree to which its applications are multihomed.At the same time,the seller is more likely to accept such payments from the owner of a platform with which it shows a betterfit than from the owner of a plat-form with which it shows a worsefit.We use the prior sales success of the seller’s applications among the buyers of the platform as an indicator of seller–platformfit.We hypothesize the following:H4:Seller-level multihoming increases as seller–platformfit decreases.Note that a potential counterargument may lie in a coop-eration dilemma known in the economics literature as the “holdup problem.”This problem emerges in situations in which cooperation between two market players(in our case,the platform owner and the seller)is the most effi-cient strategy,and yet the players refrain from cooperation because they do not want to give the other party increased bargaining power(Edlin and Reichelstein1996;Schwarz and Takhteyev2010).However,in our context,this holdup problem is unlikely to occur,because the exclusivity agree-ments between sellers and platform owners are made for each application separately,often before the application is developed.In our empirical tests of the H3and H4,we again control for the number of applications that already exist for the platform,inertia in multihoming decisions,and the characteristics of the platforms that are time-invariant (see previous discussion)using platform dummies.DataWe test our hypotheses using data from the video game console industry.This sectionfirst describes this research context and our data collection procedures,after which it turns to the operationalization and description of the mea-sures we employ.Research Context:The Video GameConsole IndustryThe video game console industry dates back to the early 1970s.In1972,the television maker Magnavox introduced Odyssey,thefirst home video game console.The system came with12games,including versions of tennis and Ping-Pong,and more than100,000game consoles were sold by the end of1972.Since then,seven sequential generations of game consoles have been introduced,one everyfive to six years.Each generation is typically characterized by a superior technology,often with new and superior console accessories,and consists of a small number of competing,incompatible video game consoles and a collection of game titles.In thefirst generations of home video game con-soles,the games were typically developed and published by the console owners.Over time,platforms(i.e.,consoles) and applications(i.e.,games)in the video game industry became increasingly separated,with large publishers spe-cializing in games,without a footprint in console manufac-turing(e.g.,Electronic Arts).The popularity of video game consoles has grown rapidly in the past two decades,with more than55million seventh-generation game consoles sold in the United States as of March2010(Digital Digest2010).Recently,playing video games was rated the top fun entertainment activ-ity by American households,outpacing watching televi-sion,surfing the Internet,reading books,and going to or renting movies(Interactive Digital Software Association 2001).ACNielsen’s2005study“Benchmarking the Active Gamer”shows that the demographic of gamers widened between2000and2005,with more women playing and an emerging market of males in the25-to34-year age range. This study also found that gamers spent more time(25% of their leisure time)playing games(BusinessWeek2005). The video game console market is well suited for test-ing the implications of multihoming in two-sided markets. First,this market is often cited as the canonical exam-ple of a two-sided market(Clements and Ohashi2005; Shankar and Bayus2003).Second,there is sufficient vari-ation in this market,both over time and across consoles, in multihoming,the number of applications,and platform sales.Third,the business of publishing video games today is similar to the publishing of DVDs and other entertain-ment products.Our data cover the sales of12home video game con-soles from three consecutive generations(i.e.,generations 5,6,and7),including unit sales and quality ratings for all games sold for the analyzed systems(4230titles)in the United States over154consecutive months starting from July1995.The consoles include Sega Saturn,Sony PlayStation,Nintendo64,3DO Multiplayer,Atari Jaguar, Sega Dreamcast,Sony PlayStation2,Nintendo GameCube, Microsoft Xbox,Microsoft Xbox360,Sony PlayStation3, and Nintendo Wii.Thefifth video game console generation is known as the 32-/64-bit generation.This generation lasted approximately from1993to2002.The three dominating consoles of the fifth generation are Sega Saturn(introduced in May1995), Sony PlayStation(introduced in September1995),and Nin-tendo64(introduced in September1996).Other consoles that were part of this generation and are covered in our data are the3DO Multiplayer and Atari Jaguar,but they had a much lower sales level and no significant impact on the structure of the market.The sixth video game console generation,also known as the128-bit generation,refers to video game consoles that were introduced between1999and2001.Platforms of the sixth generation include Sega’s Dreamcast(introduced in September1999),Sony’s PlayStation2(introduced in Octo-ber2000),and the Nintendo GameCube and Microsoft’s Xbox(both introduced in November2001).The consoles of the sixth generation showed great similarity in terms of their technological characteristics.The seventh video game console generation(the current generation)includes game consoles that have been released44/Journal of Marketing,November2011。