3+SCOTT+-+Cultural+Industry+2010

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:733.92 KB

- 文档页数:16

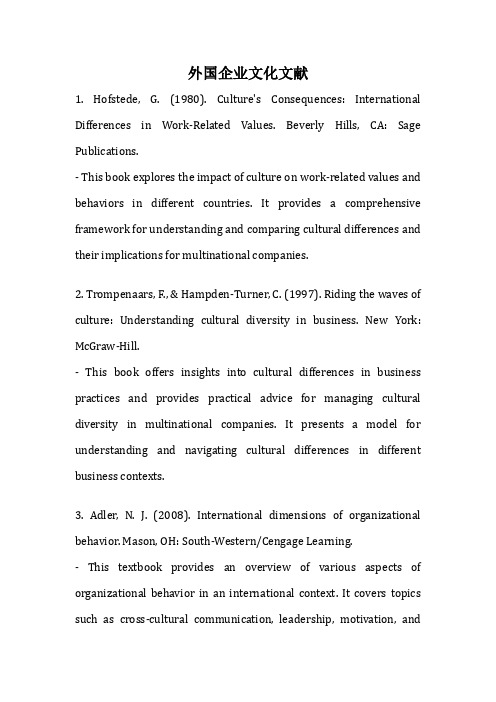

外国企业文化文献1. Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture's Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.- This book explores the impact of culture on work-related values and behaviors in different countries. It provides a comprehensive framework for understanding and comparing cultural differences and their implications for multinational companies.2. Trompenaars, F., & Hampden-Turner, C. (1997). Riding the waves of culture: Understanding cultural diversity in business. New York: McGraw-Hill.- This book offers insights into cultural differences in business practices and provides practical advice for managing cultural diversity in multinational companies. It presents a model for understanding and navigating cultural differences in different business contexts.3. Adler, N. J. (2008). International dimensions of organizational behavior. Mason, OH: South-Western/Cengage Learning.- This textbook provides an overview of various aspects of organizational behavior in an international context. It covers topics such as cross-cultural communication, leadership, motivation, andteamwork, offering insights into the challenges and opportunities of managing multinational teams.4. Hall, E. T. (1976). Beyond culture. New York: Doubleday.- In this book, Edward T. Hall explores the concept of culture and its impact on communication and behavior. It delves into the differences between high-context and low-context cultures and provides valuable insights for understanding and navigating cultural differences in international business settings.5. Schein, E. H. (2010). Organizational culture and leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.- This book examines the role of organizational culture in shaping the behavior and performance of companies. It explores the various layers of culture within organizations and offers practical guidance for managing and transforming company culture in a global context.These references provide a range of perspectives on the topic of foreign company culture and can serve as valuable resources for understanding and managing cultural differences in international business.。

2010年专八真题听写参考答案1 tones of voice2 huskiness3 universal signal;4 thought or uncertainty5 indifference6 honesty7 distance;8 situation;9 mood; 10 unconsciously same posture特邀著名国内英语考试郑家顺教授分享2010年专八考试权威答案,以下为听力部分1. C2. A3. D4. A5. C6. B7.C8. D9. D 10. A11.A 12.C 13.B 14.A 15.D16.C 17.C 18.A 19.D 20.B21. A 22.B 23. B 24.B 25. C26.A 27.D 28.D 29.A 30.C2010年专八真题改错原文So far as we can tell, all human languages are equally complete and perfect as instruments of communication: that is, every language appears to be as well equipped as any other to say the things its speakers want to say. It may or may not be appropriate to talk about primitive peoples or cultures, but that is another matter. Certainly, not all groups of people are equally competent in nuclear physics or psychology or the cultivation of rice or the engraving of Benares brass. But this is not the fault of their language. The Eskimos can speak about snow with a great deal more precision and subtlety than we can in English, but this is not because the Eskimo language (one of those sometimes miscalled ’primitive’) is inherently more precise and subtle than English. This example does not bring to light a defect in English, a show of unexpected ’primitiveness’. The position is simply and obvio usly that the Eskimos and the English live in different environments. The English language would be just as rich in terms for different kinds of snow, presumably, if the environments in which English was habitually used made such distinction important.Similarly, we have no reason to doubt that the Eskimo language could be as precise and subtle on the subject of motor manufacture or cricket if these topics formed part of the Eskimos’ life. For obvious historical reasons, Englishmen in the nineteenth century could not talk about motorcars with the minute discrimination which is possible today: cars were not a part of their culture. But they had a host of terms for horse-drawn vehicles which send us, puzzled, to a historical dictionary when we are reading Scott or Dickens. How many of us could distinguish between a chaise, a landau, a victoria, a brougham, a coupe, a gig, a diligence, a whisky, a calash, a tilbury, a carriole, a phaeton, and a clarence ?2010年专八真题改错参考答案1 be后插入as;2 their改为its;3 There改为It;4 Whereas改为But5 further 改为much6 come改为bring;7 similar改为different;8 will改为would;9 as important去掉as; 10 the part去掉the2010年专八真题人文知识参考答案31、D;32、A;33、D;34、A;35、C;36、D;37、A;38、A;39、C;40、B。

经济学专业本科生必读书目《资本论》,第1-3卷,马克思,人民出版社,1975。

《资本论》,第一卷,法文版中译本,马克思,中国社会科学出版社,1983。

《马克思恩格斯选集》,第1-4卷,马克思、恩格斯,人民出版社,1972。

《论马克思主义经济学》,上、下卷,曼德尔,商务印书馆,1979。

《晚期资本主义》,曼德尔,黑龙江人民出版社,1983。

《〈资本论〉新英译本导言》,欧内斯特·孟德尔,中共中央党校出版社1991年版。

《重读〈资本论〉》,本·法因等,山东人民出版社1994年版。

《读〈资本论〉》,路易·阿尔都塞、艾蒂安·巴里巴尔,中央编译出版社2001年版。

《垄断资本》,保罗·巴兰、保罗·斯威齐,商务印书馆,1977。

《资本主义进展论》,保罗·斯威齐,商务印书馆,1997。

《劳动与垄断资本》,哈里·布雷弗曼,商务印书馆,1978。

《生产力的四次革命》,于尔根·库钦斯基,商务印书馆,1984。

《十八世纪产业革命》,保尔·芒图,商务印书馆,1991。

《看得见的手》,艾尔弗雷德·D·钱德勒,商务印书馆,2001。

《多样化的资本主义》,理查德·惠特利,新华出版社,2004。

《比较政治经济学理论》,罗纳德·H·奇尔科特,社会科学文献出版社,2001。

《现代世界体系的混沌与治理》,乔万尼·阿瑞吉、贝弗里·J·西尔弗,生活·读书·新知三联书店,2003。

《现代资本主义》,托马斯·K·麦格劳,江苏人民出版社,2000。

《股票资本主义:福利资本主义》,罗纳德·多尔,社会科学文献出版社,2001。

《资本主义的模式》,戴维·柯茨,江苏人民出版社,2001。

《资本主义的进展时期》,罗伯特·阿尔布里坦等,经济科学出版社,2003。

外交政策分析的路径与模式[①]《外交评论》2011年第6期内容摘要:虽然外交政策是我们理解国际关系的关键,但与国际政治研究相比,外交政策研究尚处于“初级阶段”。

本文对外交政策分析的特征、价值进行了总结,并从社会科学研究的四种分析模式出发,对现有外交政策分析文献进行了分类归纳。

根据本文的归纳,外交政策分析存在四种路径九种模式。

但是,不管那种路径与模式都未能解决外交政策分析的三个关键难题,因而并不能对外交政策提供令人满意的分析。

为此,本文最后指出,如何整合不同路径与不同模式以提供一个综合分析框架是外交政策分析面临的难题。

关键词:外交政策分析、施动者-结构、解释、理解[作者简介]李志永,湖北人,对外经济贸易大学国际关系学院讲师,主要研究方向为国际政治理论、外交政策分析、中国外交、公共外交等,lizhiyong0424@。

通信地址:北京市朝阳区惠新东街10号对外经济贸易大学国际关系学院,诚信楼8层72号信箱(100029)。

克里斯托夫·希尔指出,“外交政策是我们理解国际关系的核心部分,即使它远难称得上这一问题的全部。

由于某些好的和坏的理由,它目前被忽视了,但它必须回答中心位置。

”[②]保罗·科维特(Paul Kowert)也指出,“由利益可能截然不同的公民所组成的民族国家怎样才能选择合适的外交(或任何其他)政策以服务于‘公共’利益呢?这一集体行为问题以及与其相关的国家合作途径问题,都是国际关系的主导性问题。

”[③]换句话说,国家的外交政策到底是如何决定的及其行为规律构成了国际关系研究的主导性问题,这正是外交政策分析要回答的根本主题。

本文将从方法论与认识论入手,对外交政策分析的主要路径与模式进行回顾与总结,以推动我们对外交政策的理解,促进外交政策分析研究的深化。

一、外交政策分析的特征与价值国际关系是行为体(现今主要是国家)互动造就的人类现象,而就单个行为体而言,任何由国家引起的重大国际政治现象均是不同外交决策或决策[④]相互作用的结果。

大学英语精读第三版第二册课后答案Unit 1: Cultural StudiesExercise 1:a. Culture refers to the beliefs, behaviors, customs, and practices of a particular society or group.b. Cultural awareness is important because it allows us to understand and appreciate different perspectives, customs, and traditions.c. Cultural artifacts are objects or items that are created by a particular culture, often representing its values, history, or way of life.d. Cultural exchange refers to the sharing and interaction of different cultures, often through communication and activities.e. Cultural identity is the sense of belonging and identification with a particular culture or group.f. Cultural shock is the feeling of disorientation, confusion, or discomfort when encountering a new or different culture.g. Cultural heritage refers to the cultural aspects inherited from past generations, including traditions, customs, and historical sites.h. Cultural assimilation is the process of adopting and integrating into a new culture, often leading to a loss of one's original culture.Exercise 2:a. The United Kingdom is known for its rich cultural heritage, including historical landmarks such as Stonehenge and Buckingham Palace.b. In Japan, the tea ceremony is an important cultural practice that demonstrates grace, hospitality, and respect.c. Native American tribes have a diverse range of cultural practices, including traditional dances, storytelling, and art.d. Chinese calligraphy is not only a form of written communication but also an artistic expression of the culture's beauty and wisdom.e. Bollywood films from India have gained international recognition for their vibrant music, colorful costumes, and dramatic storytelling.Unit 2: Literature and FilmExercise 1:a. Setting: The setting of a story refers to the time, place, and environment in which it takes place. It helps create the atmosphere and context for the events.b. Plot: The plot is the sequence of events that make up a story. It includes the main conflict, rising action, climax, and resolution.c. Characterization: Characterization is the process of creating and developing characters in a story. It includes their traits, personalities, and motivations.d. Theme: The theme is the central idea or message conveyed by a literary work. It often explores universal truths or human experiences.e. Symbolism: Symbolism is the use of symbols or objects to represent deeper meanings or concepts within a story.f. Foreshadowing: Foreshadowing is a literary device used to hint or suggest future events or outcomes in a story.g. Irony: Irony is the contrast between what is expected and what actually happens. It can be used to create humor, dramatic effect, or emphasize a point.h. Point of View: Point of view refers to the perspective from which a story is told. It can be first-person (narrator is a character in the story) or third-person (narrator is outside the story).Exercise 2:a. In George Orwell's novel "1984," the setting of a dystopian future creates a dark and oppressive atmosphere, reflecting the theme of government control and surveillance.b. Shakespeare's play "Romeo and Juliet" explores the theme of love and fate through the tragic story of two young lovers from feuding families.c. In F. Scott Fitzgerald's novel "The Great Gatsby," the green light at the end of Daisy's dock symbolizes Gatsby's hopes and dreams for the future.d. The film "The Shawshank Redemption" uses foreshadowing to hint at the eventual escape of the protagonist, Andy Dufresne, from prison.e. In the short story "The Necklace" by Guy de Maupassant, the irony lies in the fact that the protagonist, Mathilde Loisel, sacrifices her happiness for a necklace that turns out to be fake.Unit 3: Science and TechnologyExercise 1:a. Technology refers to the application of scientific knowledge and tools to solve problems or improve processes.b. Artificial intelligence (AI) is a field of computer science that focuses on the development of intelligent machines that are capable of performing tasks that would typically require human intelligence.c. Genetic engineering is the manipulation of an organism's genes or genetic material to achieve desirable traits or outcomes.d. Nanotechnology is the science, engineering, and application of materials and devices at the nanometer scale.e. Renewable energy is energy that is derived from sources that are naturally replenished, such as sunlight, wind, or biomass.f. Robotics is the branch of technology that deals with the design, construction, and operation of robots.g. Virtual reality (VR) is a simulated experience that can be similar to or completely different from the real world. It is achieved through the use of computer technology and immersive devices.h. Biotechnology is the use of living organisms or biological processes to develop or create useful products or solutions.Exercise 2:a. The advancement of technology, such as the development of smartphones and social media, has revolutionized communication and transformed the way people connect and interact with each other.b. Genetic engineering offers the potential to cure and prevent genetic diseases, but it also raises ethical concerns regarding manipulating the building blocks of life.c. Nanotechnology has the potential to revolutionize various industries, including medicine, electronics, and energy, through the development of smaller, more efficient materials and devices.d. The use of renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind power, can help reduce dependence on fossil fuels and combat climate change.e. Robotics has the potential to automate and streamline various industries, leading to increased efficiency and productivity, but it also raises concerns about job displacement and ethical considerations.f. Virtual reality technology has expanded beyond entertainment and gaming, with applications in healthcare, education, and training.g. Biotechnology has led to advancements in medicine, agriculture, and environmental conservation, but it also raises ethical concerns regarding the manipulation of living organisms and potential risks.Note: This is a general overview of the topics covered in "大学英语精读第三版第二册." It is advisable to refer to the specific textbook for detailed answers to the exercises.。

英语国家社会与文化》考试试卷(A卷)适用班级考试时间 120 分钟学院外国语班级学号姓名成绩题号一二三四五六七八九十总分分数得分一、Fill in the following information gaps(20%)(1 point each)1.England is a highly ____1____ country ,with more than 80% of its population living in cities ,and about 2% of the population working in agriculture.2.The first permanent settlement in North America was established, intoday's __ 2 in the year of 16073.The American transcendentalist, _____3______- published a startling book called Nature he claimed by studying and respecting to nature individual could reach a higher spiritual state without form religion .4.The U.S. federal government consist of the following three branches____4____, the legislative and the judicial .5.One advantage of corporation over sole proprietorship and partnership is that it has _____5___,so investors risked only the amount of their investment and not their entire assets6.The best -known stock exchange is ___6_________located in Wall Street area of New York City7.WASP stands for ______7_______.8.The majority of the Catholics in the U.S. are descendants of immigrants from _______8______,Italy and Poland.9. _______9______ , they refer to the five novels written by Fennimore Cooper.10.A collection of poems written by_____10____, it is a ground-breaking book. That is Leaves of Grass.11.An jazz music ensemble of musicians consists of two sections: the front line and ____11_____.12.M.B.A and G.R.E. stand for Master of Business Administrationand _______12______ in U.S. education.13.In the U.S., B.A. and B.S. stand for Bachelor of Artsand _______13________in higher education.14.The two most well known computer companies are IBM and_____14____ in the United States.15.In the 11th century Britain was invaded by a group of__15____ from northern France .16.Two Scottish cities which have a ancient and internationally respected universities _______16________ and Glasgow.17.The Britain, the official head of state is now the King while the real center of political life is in ______17________ .18.The British Constitution consists of _____18________ ,the common laws and conventions.19.In jazz music major musical instrument include violin,_____19_____,piano,trombone , cymbal ,bell, hollow wooden block,chimes ,drum, guitar etc.20.In the American education , A.A. stands for ____20______.得分二、Choose the correct answer for each of the following (35%)(1 point each)1. Which of the following was NOT one of the three forces that led to the modem development of Europe?A. The growth of capitalism.B. The Renaissance.C. The Religious Reformation.D. Tile spiritual leadership of the Roman Catholic Church.1.Who was the first to start the Religious Revolution that brought about the modern development of Europe?A. Martin LutherB. John CalvinC. John LockeD. John Adams3. Which of the following American values did NOT come from Puritanism?A. separation of state and church.B. respect of education.C. intolerant moralism.D. a sense of mission.4. The theory of American politics and the American Revolution originatedmainly fromA. George Washington.B. Thomas Jefferson.C. John Adams.D. John Locke.5. Which of the following was NOT a denomination of Protestantism?A. Catholics.B. Puritans.C. Quakers.D. Church of England.6. Which of the following was NOT the cause that brought about the development of American Industrial Revolution.A. introduction of factory systemB. system of mass productionC. construction of railroadD. religious liberty7.Service industry does not include_______________.A. BankingB. management consultationB. Airline C .steelmaking8. One of the problems with American agriculture that critics accuses both corporate and family farmers of damaging the __________.A. tourism attractionB. environmentC. cultural balanceD. economic development9. The latest technology that farmers have adopted isA. artificial fertilizersB. pesticideC. tractorsD. computers10. Which of the following was NOT a Protestant denomination?A. The Baptists.B. The Catholics.C. The Methodists.D. The Presbyterians.11. In the United States, people go to church mainly for the following reasons exceptA. for finding a job in society.B. for having a place in a community.C. for identifying themselves with dominant values.D. for getting together with friends.12. Which of the following statements is NOT correct according to the American laws?A. American mainstream culture is based on Protestantism.B. Protestant Church is an established church by law in the U.S.C. The Catholic Church is the largest single religious group in the U.S.D. The largest church is of the Protestant faith in the U.S.13.Which of the following was written by Thoreau?A. NatureB. WaldenC. The Scarlet LetterD. The Fall of the House of Usher14. ______________was mainly interested in writing about Americans living in Europe.A. Henry JamesB. Mark TwainC. William Dean HowellsD. Stephen Crane15. Three of the following authors are Nobel Prize winners. Which one is not.A. Ernest HemingwayB. Eugene O'NeillC. William FaulknerD. F. Scott Fitzgerald16.______________does NOT belong to the "Lost Generation".A. John Dos PassosB. Ernest HemingwayC. F. Scott FitzgeraldD. John Steinbeck17. ______was NOT written by Hemingway.A. Light in AugustB. The Sun Also RisesC. A Farewell to ArmsD. For Whom the Bell Tolls18. The typical Christmas meal consists of _______ with potatoes and other vegetables____ carrots and sprouts ,this is often followed by Christmas pudding.A. turkeyB. cakesC. mince piesD. roast beef19.Both public and private Universities depend on the following sources of income except,A. investmentB. student tuitionC. endowmentsD. government funding20. The legislative branch of the U.S. consists of congress that is divided into:A. the House of Representatives and the SenateB. the House of Representative and the SenatesC. the House of commons and the House of LordsD. the House of Common and the House of Lord21. In the U.S. ,Which of the following does NOT belong to the white-collar crime?A. briberyB. tax evasionC. false advertisingD. robbery22.Which of the following is not a team game?A. volleyballB. bowlingC. soccerD. field hockey23 According to the author, jazz music gains acceptance in all classes in American society because of the following reasons. Which is the exception?A. It initially appealed to the young and rebellious.B. Jazz musicians worked Indian American music into the music.C. Jazz music was made modified and became more refined.D.Both A and C.24. Blues was derived from a blend of field chantey and spiritual which isA. a form of rock 'n, roll singing popular among American teenagers.B. a form of operatic singing originated from Southern European countries.C. a form of country music singing.D. a form of hymn singing prevalent in African-American Christian churches.25. Which of the following is NOT considered a characteristic of London?A. The cultural centre.B. The business centre.C. The financial centre.D. The sports centre.26. Which of the following can NOT be found in London?A. Teahouses.B. Galleries.C. Museums.D. Theatres.27. The Tower Of London, a historical sight, located in the centre of London, was built byA. King HaroldB. Robin HoodC. Oliver CromwellD. William the Conqueror28. The ________provides a fair way for deciding whom to admit when then they have 10 or 12 applicants for every first year students seat in the U.S.A.SATSB.NBAC.NEED.CBA29. Northern Ireland is the smallest of the four nations, but is quite well-known in the world forA. its most famous landmark, the "Giant's Causeway".B. its rich cultural lifeC. its low living standardsD. its endless political problems30. A masterpiece ,______ to explore certain moral themes such as guilt ,pride and emotional precession by Nathanial HawthorneA. The Scarlet LetterB. Catch -22C. The Grapes of WrathD. Moby Dick31. Which of the following about the House of Commons is NOT true?A. Members of Parliament elect the Prime Minister and the Cabinet.B. MPs receive salaries and some other allowances.C. MPs are expected to represent the interests of the public.D. Most MPs belong to the major political parties.32. ___________ made the first desktop PC.A. Thomas EdisonB. Apple computersC. Tow tong amateur inventorsD. Samuel F.B. More33. These ____ and _____ stand today as Wales' great tourist attractions. Tourism is an important industryA. castles and estatesB. Hadrian's WallC. Giant's CausewayD. Royal Pavilion34. The British Queen decided to open__________ to summer tourists to raise money, which caused a lot criticism from the public.A. the Tower of London .B. British Museum.C. Buckingham Palace and Windsor Castle.D. Westminster Abbey35. Louis Armstrong played theA . cornet. B. drum. C. clarinet D. piano.得分三、Give brief explanations of the following ideas (Choose 5 from 8 to present on the paper )(25%)(5 point each)1.the meaning of being an American according to Crevecoeur2.the Anglo-Saxons3.two immigration movements to the Americas4.functions of British Parliament5.Three Faiths in the U.S.6. the "Lost Generation"7.Jazz music8. the meaning of the poverty in the U.S.得分四、Analyze the roots that have favored the success of American business and industry(20%)《英语国家社会与文化》考试试卷(A卷)Key Answer一、Fill in the following information gaps(20%)(1 point each)1 .urbanized 2. Virginia3. Ralph Waldo Emerson 4 .the executive5. limited liability 6 .New York Stock Exchange7. the White Anglo-Saxon Protestant 8. Ireland9. the Letherstocking Tales 10. Walt Whitman11. the percussion 12 .Graduate Record Examination13. Bachelor of Science 14. Apple15 .the Normans 16. Edinburgh17 .the House of Commons 18 .statute law19 .clarinet 20.Associate of Arts二、Choose the correct answer for each of the following (35%)(1 point each)1-5 DAADA 6-10 DDBAB 11-15 ABBAD 16-20 DAAAA21-25 DDDDA 26-30 ADADA31-35 ACACA三、Give brief explanations of the following ideas (Choose 5 from 8 to present on the paper )(25%)(5 point each)1 .the meaning of being an American according to CrevecoeurAccording to Crevecoeur the American was a new man with the mixed blood of Europeans or their descendants. This new man left behind him all the ancient European traditions and received ones in the New World. In North America, all individuals were melted into a new race of the American. This new man acted upon new principles, entertained new ideas and formed new opinions.2. the Anglo-SaxonsThe Anglo-Saxons were two groups of Germanic peoples who settled down in England from the 5th century . They were regarded as the ancestors of the English and the founders of England.3. two immigration movements to the AmericasThe American continents were peopled as a result of two long-continuing immigration movements, the first from Asia and the second from Europe and Africa.4 .functions of British ParliamentParliament has a umber of different functions. First and foremost ,it passes laws. Another important function is that it provides the means of carrying on the work of government by voting for taxation . Its other roles are to scrutinize government policy, administration and expenditure and to debate the major issues of the day.5.Three Faiths in the U.S.By the 1950s, the three faiths model of American religion had developed. Americans were considered to come in three basic varieties: Protestant, Catholic and Jewish, the order reflecting the strength in numbers of each group.6.the "Lost Generation"In the aftermath of World War I, many novelists produced a literature of disillusionment. Some lived abroad. They were known as the "Lost Generation". The two most representative writers of the "Lost Generation" were Hemingway and Fitzgerald.7.Jazz musicEarly jazz music first appeared in the Southern city of New Orleans at the end of the 19th century .It was a blend of folk music, Work chants, spirituals, marches , and even European classical music. A defining mark of this early New Orleans jazz was that a group of musicians improvising their notes in changing chords around a specific melodic line. All jazz bands use such instruments as a trumpet, a clarinet, a trombone, and percussion instruments like the drum, banjo, and guitars. Jazz developed into the 1920's with two different styles, namely, the Chicago style jazz and the New York style8.the meaning of the poverty in the U.S.Poverty in the U.S. does not supplely mean that the poor do not live quite as well as other citizens. It means many old people eating dog and cat food to supplement their diets. It means malnutrition and deprivation for hundreds of thousands of children. It means greater susceptibility to disease, to alcoholism, to victimization by criminals, and to mental disorders. It often means unstable marriages, slum housing, illiteracy, ignorance, inadequate medical facilities, and shortened life expectancy. Poverty can mean low self-esteem, despair, and stunting of human potential.四、Analyze the roots that have favored the success of American business and industry (20%)No single factor is responsible for the successes of American business and industry. Bountiful resources, the geographical size of the country and population trends have all contributed to these successes. Religious, social and political traditions; the institutional structures of government and business; and the courage, hard work and determination of countless entrepreneurs and workers have also played a part.The vast dimensions and ample natural resources of the United States proved from the first to be a major advantage for national economic development. With the fourth largest area and population in the world, the United States still benefits greatly from the size of its internal market. The Constitution of the United States bars all kinds of internal tariffs, so manufacturers do not have toworry about tariff barriers when shipping goods from one part of the country to another.Population grew fast enough to supply both workers and consumers for American businesses.(eg Thanks to several waves of immigration, the United States gained population rapidly Rapid growth helped to promote a remarkable mobility in the American population a mobility that contributes a useful flexibility to business life. )The American people have possessed to an unusual degree the entrepreneurial spirit that finds its outlet in such business activities as manufacturing, transporting, buying and selling. Some have traced this entrepreneurial drive to religious sources. (eg)A variety of institutional factors have favored the success of American business and industry. (eg Mindful of the potential for abuse that lay in a powerful government, the founders of America's political institutions sought to limit governmental powers while widening opportunities for individual initiative. The relative reluctance of American political leaders to intervene in economic activities gave great freedom to market forces. By channeling economic initiative into activities that promised the greatest return on investment,free-market institutions fostered dynamic growth and rapid change. One result was a rapid accumulation of capital, which could then be used to produce further growth.)。

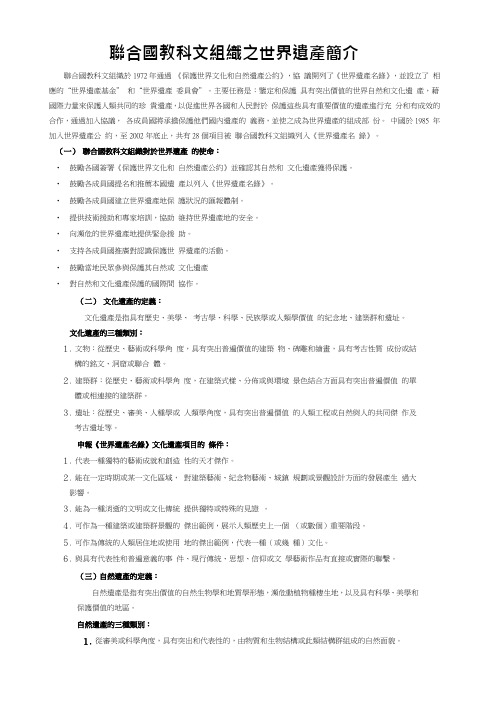

聯合國教科文組織之世界遺產簡介聯合國教科文組織於1972年通過《保護世界文化和自然遺產公約》,協議開列了《世界遺產名錄》,並設立了相應的“世界遺產基金”和“世界遺產委員會”。

主要任務是:鑒定和保護具有突出價值的世界自然和文化遺產,藉國際力量來保護人類共同的珍貴遺產,以促進世界各國和人民對於保護這些具有重要價值的遺產進行充分和有成效的合作,通過加入協議,各成員國將承擔保護他們國內遺產的義務,並使之成為世界遺產的組成部份。

中國於1985 年加入世界遺產公約,至2002年底止,共有28個項目被聯合國教科文組織列入《世界遺產名錄》。

(一)聯合國教科文組織對於世界遺產的使命:‧鼓勵各國簽署《保護世界文化和自然遺產公約》並確認其自然和文化遺產獲得保護。

‧鼓勵各成員國提名和推薦本國遺產以列入《世界遺產名錄》。

‧鼓勵各成員國建立世界遺產地保護狀況的匯報體制。

‧提供技術援助和專家培訓,協助維持世界遺產地的安全。

‧向瀕危的世界遺產地提供緊急援助。

‧支持各成員國推廣對認識保護世界遺產的活動。

‧鼓勵當地民眾參與保護其自然或文化遺產‧對自然和文化遺產保護的國際間協作。

(二)文化遺產的定義:文化遺產是指具有歷史、美學、考古學、科學、民族學或人類學價值的紀念地、建築群和遺址。

文化遺產的三種類別:1.文物:從歷史、藝術或科學角度,具有突出普遍價值的建築物、碑雕和繪畫,具有考古性質成份或結構的銘文、洞窟或聯合體。

2.建築群:從歷史、藝術或科學角度,在建築式樣、分佈或與環境景色結合方面具有突出普遍價值的單體或相連接的建築群。

3.遺址:從歷史、審美、人種學或人類學角度,具有突出普遍價值的人類工程或自然與人的共同傑作及考古遺址等。

申報《世界遺產名錄》文化遺產項目的條件:1.代表一種獨特的藝術成就和創造性的天才傑作。

2.能在一定時期或某一文化區域,對建築藝術、紀念物藝術、城鎮規劃或景觀設計方面的發展產生過大影響。

3.能為一種消逝的文明或文化傳統提供獨特或特殊的見證。

第30卷情摇报摇杂摇志摇第1期Vol.30摇No.1摇摇摇摇摇摇摇摇摇摇摇摇摇摇摇2011年1月摇摇摇摇摇摇摇摇摇摇摇JOURNALOFINTELLIGENCEJan.摇2011威客的成因、本质及全球化交易影响因素研究*———基于网络文化创意产业的视角李摇燕1,2(1.四川大学文学与新闻学院摇成都摇610064;2.西南大学图书馆摇重庆摇400715)摘摇要摇2009年7月22日国务院通过《文化产业振兴规划》,标志着我国的文化产业首次被提到国家规划层面,正面临着历史性的发展机遇。

在此背景下,网络文化创意产业新模式———威客的重要研究价值凸显出来。

本文首次从文化创意产业角度对威客的成因、本质以及影响全球化交易的因素进行了探讨,不但从理论上对这一新生事物进行了必要的研究和梳理,而且对业界的操作实践也有较大的借鉴意义。

关键词摇威客摇网络文化产业摇微创意摇长尾理论中图分类号摇G203摇摇摇摇摇摇文献标识码摇A摇摇摇摇摇摇摇文章编号摇1002-1964(2011)01-0190-06TheCause,EssenceandGlobalTrade'sInfluencingFacto rsofWitkey———BasedonNetworkCreativeIndustryLIYan1,2(1.CollegeofLiteratureandJ ournalism,SichuanUniversity,Chengdu610064;2.SouthwestUniversityLibrary,Chongqing 400715)Abstract摇The'CultureIndustryPromotionPlan'waspassedbyStateCouncilinJuly22,200 9.ItindicatedthatChina'sculturalindustryhadbeenpromotedtothenationalplanninglev elfirsttime,andwasfacingahistoricopportunity.Inthisbackground,theresearchvalueofWitkey ,anewmodelofculturalandcreativeindustrieswashighlighted.Thispaperstudiesthecause,esse nceandglobaltrade'sinflu鄄encingfactorsofWitkeyfromtheperspectiveofculturalandcreativeindustriesfirsttime.Itmayn otonlydosomenecessaryresearchonanewthingtheoretically,butalsoprovidesomevaluableref erencestothepracticeofthisindustry.Keywords摇witkey摇networkcultureindustry摇micro-creativity摇LongTail集中在商业模式和商业前景等方面,研究人员大多为0摇引摇言商学院的专家学者。

⽂化产业与经济发展的关系⽂化产业与经济发展的关系⽅⾯在国外,Greco ( 1999)【1】分析了美国出版业对经济增长的贡献; Hjorth-Andersen ( 2000)【2】则对丹麦的出版业对经济增长的影响进⾏了分析; Dominic Power ( 2002)【3】使⽤1970 - 1999 年的时间序列数据,说明了⽂化产业的发展有助于提⾼瑞典的就业⽔平,推动经济增长; David Throsby ( 2004)【4】利⽤投⼊产出分析⽅法以及CGE 模型等对⽂化产业的运作以及如何影响经济和社会进⾏了研究; Allen( 2004)【5】采⽤2001 年美国48个洲的截⾯数据进⾏了实证研究,结果显⽰美国⽂化产业的发展改变了企业的投资模式,促进消费结构升级,推动了经济增长。

Pratt (1997) 【6】认为⽂化产业是现代经济体系重要的、增长的部分。

在⽂化产品的消费⽅⾯,诺贝尔经济学奖获得者斯蒂格勒和贝克尔1977 年在论⽂《偏好是⽆可争辩的》⼀⽂中指出,从⾳乐消费中产⽣的边际效⽤依赖于消费者⼰经消费的总量及其欣赏⾳乐的能⼒,⽽欣赏⾳乐的能⼒⼜是以往⾳乐消费的函数。

⾳乐消费资本的投⼊和消费是相互促进的,⾳乐消费的边际效益会随着时间⽽增长。

Wynne (1992a) 【7】研究了英国⽂化产业发展与相关城市和地区发展的关系发现,⽂化产业迅速增长是不仅是英国的⼤城市经济发展的显著推动⼒,⽽且还是英格兰中北部⼀些旧的⼯业城镇经济发展的显著推动⼒。

Gnad (2000) 【8】的研究也发现⽂化产业的发展是德国Ruhr -Gebiet地区经济发展的显著推动⼒。

Philo 和Kesrns (1993)【9】 , Graham ,Ashworth 和Tunridge (2000)【10】认为⽂化产业的迅速发展可以升级与重塑地区⽂化资源,提升各处⽂化资源的历史和艺术的吸引⼒,进⽽吸引更多的参观者;还可以提升地区形象,吸引⾼层次的投资者和⾼素质的劳动者,促进该地区的经济增长在国内,张潇扬(2006) 【11】认为⽂化产业园能够有效促进⽂化产业与⼯业制造业的互动并带动⽂化产业发展。

介绍文学艺术作品的英语作文八年级全文共3篇示例,供读者参考篇1Introduction to Literary and Artistic WorksLiterary and artistic works hold a special place in human society, serving as a reflection of our thoughts, emotions, and experiences. These works encompass a diverse array of genres, from novels and poems to paintings and sculptures, each offering a unique perspective on the world around us. In this essay, we will explore the significance of literature and art, highlighting some of the most notable works that have left a lasting impact on culture and society.One of the most iconic literary works of all time is William Shakespeare's play "Romeo and Juliet." Set in Verona, Italy, the tragedy of two young lovers from feuding families has captured the hearts of audiences for centuries. Through its timeless themes of love, fate, and conflict, "Romeo and Juliet" continues to resonate with readers and theatergoers around the world.In the realm of poetry, the works of Emily Dickinson stand out as a shining example of lyrical beauty and emotional depth.Known for her reclusive nature and distinctive style, Dickinson's poems explore themes of nature, death, and the human experience with unmatched grace and elegance. Her poem "Because I could not stop for Death" remains a classic of American literature, inspiring readers with its profound insights into life and mortality.Moving beyond the written word, visual art also plays a vital role in the world of creativity and expression. The works of Vincent van Gogh, a Dutch post-impressionist painter, are among the most beloved and celebrated in art history. Van Gogh's vibrant colors, bold brushstrokes, and emotional intensity are evident in masterpieces such as "Starry Night" and "Sunflowers," which continue to enchant viewers with their beauty and power.In addition to literature and painting, the world of sculpture has also produced some truly remarkable works of art. The "Pieta" by Michelangelo, a Renaissance masterpiece depicting the Virgin Mary cradling the body of Jesus, is a prime example of the sculptor's skill and talent. Carved from a single block of marble, this sculpture captures the grief and sorrow of the moment with breathtaking realism and emotion.In conclusion, literary and artistic works hold a special place in human culture, enriching our lives with their beauty, insight, and creativity. From Shakespeare's "Romeo and Juliet" to Dickinson's poetry, from van Gogh's paintings to Michelangelo's sculptures, these works continue to inspire and enlighten us, reminding us of the power of the human imagination and the enduring legacy of creativity. As we celebrate and appreciate these masterpieces, we honor the rich tapestry of human experience and creativity that has shaped our world for generations to come.篇2Introduction to Literary and Artistic WorksLiterature and art are essential components of human culture, serving as expressions of our thoughts, emotions, and experiences. Through various forms such as novels, poems, paintings, sculptures, music, and films, artists strive to communicate their ideas and provoke feelings in the audience. In this essay, I will introduce several renowned literary and artistic works that have left a significant impact on society.One of the most influential novels in English literature is "Pride and Prejudice" by Jane Austen. Published in 1813, thisnovel tells the story of Elizabeth Bennet, a strong-willed and independent woman who navigates the challenges of love and social class in Regency-era England. Through Austen's witty prose and keen observations of human behavior, "Pride and Prejudice" explores themes of love, marriage, and societal expectations with timeless relevance.In the realm of poetry, Emily Dickinson's works stand out as powerful reflections on life, death, nature, and the human spirit. Dickinson's poems, characterized by their unconventional punctuation and syntax, delve into the complexities of existence and the mysteries of the soul. Her profound insights and evocative imagery continue to resonate with readers around the world.Moving on to visual art, the painting "Starry Night" by Vincent van Gogh is a masterpiece that captures the artist's unique vision and emotional intensity. Created in 1889 during his stay at a psychiatric hospital, this iconic work features swirling clouds, bright stars, and a tranquil village below. Van Gogh's bold use of color and expressive brushwork convey a sense of movement and energy that transcends physical reality.Sculpture is another form of artistic expression that has produced timeless masterpieces, such as Michelangelo's "David."Carved from a single block of marble in the early 16th century, this monumental statue portrays the biblical hero David in a moment of contemplation and strength. Michelangelo's meticulous attention to detail and anatomical accuracy showcase his technical skill and artistic genius.Music is a universal language that speaks to the soul and stirs emotions in listeners of all ages and backgrounds. Beethoven's Symphony No. 9, also known as the "Choral Symphony," is a monumental work that culminates in the powerful "Ode to Joy" chorus. Composed in the early 19th century, this symphony conveys themes of joy, unity, and universal brotherhood through its soaring melodies and dynamic orchestration.Lastly, the film industry has produced countless cinematic masterpieces that entertain, enlighten, and inspire audiences worldwide. One such example is Steven Spielberg's "Schindler's List," a historical drama based on the true story of Oskar Schindler, a German industrialist who saved over a thousand Jewish refugees during the Holocaust. Through its harrowing portrayal of human suffering and acts of heroism, this film challenges viewers to reflect on the complexities of morality and compassion in times of crisis.In conclusion, literature and art have the power to transcend cultural barriers, evoke deep emotions, and provokethought-provoking discussions about the human experience. By exploring the works of talented artists across various mediums, we gain a greater appreciation for the beauty, complexity, and richness of our shared humanity.篇3Introduction to Literary and Artistic WorksLiterature and art are essential components of human culture, providing us with a unique insight into the human experience. Throughout history, various literary and artistic works have captivated audiences with their creativity, emotion, and beauty. In this essay, we will explore and introduce several renowned literary and artistic works from different genres and time periods.1. The Great Gatsby by F. Scott FitzgeraldThe Great Gatsby is a classic novel written by F. Scott Fitzgerald and published in 1925. Set in the Jazz Age of the 1920s, the novel follows the lives of the wealthy and glamorous residents of West Egg, New York. Through the protagonist, Jay Gatsby, Fitzgerald explores themes of love, wealth, and theAmerican Dream. The Great Gatsby is celebrated for its vivid portrayal of the Roaring Twenties and its critique of the pursuit of material wealth.2. Mona Lisa by Leonardo da VinciThe Mona Lisa is perhaps the most famous painting in the world, created by the Italian artist Leonardo da Vinci in the early 16th century. This iconic portrait of a woman with an enigmatic smile has fascinated art lovers and scholars for centuries. The Mona Lisa showcases da Vinci's mastery of light, shadow, and perspective, as well as his ability to capture the complexity of human emotion in a single painting.3. Hamlet by William ShakespeareHamlet is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare in the late 16th century. The play follows the Prince of Denmark as he seeks revenge for his father's murder. Hamlet is renowned for its exploration of themes such as madness, revenge, and the nature of existence. Shakespeare's use of language and imagery in Hamlet has made it one of the most famous and enduring works in the English literary canon.4. The Starry Night by Vincent van GoghThe Starry Night is a masterpiece painted by the Dutch artist Vincent van Gogh in 1889. This iconic work of art depicts a swirling night sky over a village, with bright stars and a crescent moon shining down. The Starry Night is celebrated for its vivid colors, bold brushwork, and emotional intensity. Van Gogh's unique style and expressive use of paint have made this painting a symbol of artistic passion and creativity.5. Pride and Prejudice by Jane AustenPride and Prejudice is a novel written by Jane Austen and published in 1813. Set in Regency England, the novel follows the Bennet family as they navigate the complexities of love, social class, and family relationships. Pride and Prejudice is celebrated for its wit, humor, and sharp social commentary. Austen's portrayal of the strong-willed heroine, Elizabeth Bennet, has made the novel a timeless classic of English literature.In conclusion, literature and art have the power to inspire, educate, and entertain audiences around the world. The works mentioned above are just a small sample of the diverse and rich tapestry of literary and artistic creations that have shaped our cultural heritage. By exploring these works, we can gain a deeper understanding of ourselves and the world around us.。

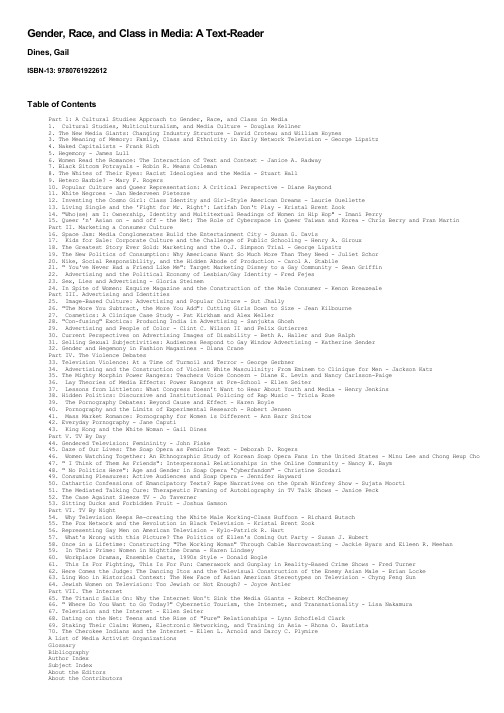

Gender, Race, and Class in Media: A Text-ReaderDines, GailISBN-13: 9780761922612Table of ContentsPart 1: A Cultural Studies Approach to Gender, Race, and Class in Media1. Cultural Studies, Multiculturalism, and Media Culture - Douglas Kellner2. The New Media Giants: Changing Industry Structure - David Croteau and William Hoynes3. The Meaning of Memory: Family, Class and Ethnicity in Early Network Television - George Lipsitz4. Naked Capitalists - Frank Rich5. Hegemony - James Lull6. Women Read the Romance: The Interaction of Text and Context - Janice A. Radway7. Black Sitcom Potrayals - Robin R. Means Coleman8. The Whites of Their Eyes: Racist Ideologies and the Media - Stuart Hall9. Hetero Barbie? - Mary F. Rogers10. Popular Culture and Queer Representation: A Critical Perspective - Diane Raymond11. White Negroes - Jan Nederveen Pieterse12. Inventing the Cosmo Girl: Class Identity and Girl-Style American Dreams - Laurie Ouellette13. Living Single and the 'Fight for Mr. Right': Latifah Don't Play - Kristal Brent Zook14. "Who(se) am I: Ownership, Identity and Multitextual Readings of Women in Hip Hop" - Imani Perry15. Queer 'n' Asian on - and off - the Net: The Role of Cyberspace in Queer Taiwan and Korea - Chris Berry and Fran MartinPart II. Marketing a Consumer Culture16. Space Jam: Media Conglomerates Build the Entertainment City - Susan G. Davis17. Kids for Sale: Corporate Culture and the Challenge of Public Schooling - Henry A. Giroux18. The Greatest Story Ever Sold: Marketing and the O.J. Simpson Trial - George Lipsitz19. The New Politics of Consumption: Why Americans Want So Much More Than They Need - Juliet Schor20. Nike, Social Responsibility, and the Hidden Abode of Production - Carol A. Stabile21. " You've Never Had a Friend Like Me": Target Marketing Disney to a Gay Community - Sean Griffin22. Advertising and the Political Economy of Lesbian/Gay Identity - Fred Fejes23. Sex, Lies and Advertising - Gloria Steinem24. In Spite of Women: Esquire Magazine and the Construction of the Male Consumer - Kenon BreazealePart III. Advertising and Identities25. Image-Based Culture: Advertising and Popular Culture - Sut Jhally26. "The More You Subtract, the More You Add": Cutting Girls Down to Size - Jean Kilbourne27. Cosmetics: A Clinique Case Study - Pat Kirkham and Alex Weller28. "Con-fusing" Exotica: Producing India in Advertising - Sanjukta Ghosh29. Advertising and People of Color - Clint C. Wilson II and Felix Gutierrez30. Current Perspectives on Advertising Images of Disability - Beth A. Haller and Sue Ralph31. Selling Sexual Subjectivities: Audiences Respond to Gay Window Advertising - Katherine Sender32. Gender and Hegemony in Fashion Magazines - Diana CranePart IV. The Violence Debates33. Television Violence: At a Time of Turmoil and Terror - George Gerbner34. Advertising and the Construction of Violent White Masculinity: From Eminem to Clinique for Men - Jackson Katz35. The Mighty Morphin Power Rangers: Teachers Voice Concern - Diane E. Levin and Nancy Carlsson-Paige36. Lay Theories of Media Effects: Power Rangers at Pre-School - Ellen Seiter37. Lessons from Littleton: What Congress Doesn't Want to Hear About Youth and Media - Henry Jenkins38. Hidden Politics: Discursive and Institutional Policing of Rap Music - Tricia Rose39. The Pornography Debates: Beyond Cause and Effect - Karen Boyle40. Pornography and the Limits of Experimental Research - Robert Jensen41. Mass Market Romance: Pornography for Women is Different - Ann Barr Snitow42. Everyday Pornography - Jane Caputi43. King Kong and the White Woman - Gail DinesPart V. TV By Day44. Gendered Television: Femininity - John Fiske45. Daze of Our Lives: The Soap Opera as Feminine Text - Deborah D. Rogers46. Women Watching Together: An Ethnographic Study of Korean Soap Opera Fans in the United States - Minu Lee and Chong Heup Cho47. " I Think of Them As Friends": Interpersonal Relationships in the Online Community - Nancy K. Baym48. " No Politics Here": Age and Gender in Soap Opera "Cyberfandom" - Christine Scodari49. Consuming Pleasures: Active Audiences and Soap Opera - Jennifer Hayward50. Cathartic Confessions of Emancipatory Texts? Rape Narratives on the Oprah Winfrey Show - Sujata Moorti51. The Mediated Talking Cure: Therapeutic Framing of Autobiography in TV Talk Shows - Janice Peck52. The Case Against Sleeze TV - Jo Taverner53. Sitting Ducks and Forbidden Fruit - Joshua GamsonPart VI. TV By Night54. Why Television Keeps Re-creating the White Male Working-Class Buffoon - Richard Butsch55. The Fox Network and the Revolution in Black Television - Kristal Brent Zook56. Representing Gay Men on American Television - Kylo-Patrick R. Hart57. What's Wrong with this Picture? The Politics of Ellen's Coming Out Party - Susan J. Hubert58. Once in a Lifetime: Constructing "The Working Woman" Through Cable Narrowcasting - Jackie Byars and Eileen R. Meehan59. In Their Prime: Women in Nighttime Drama - Karen Lindsey60. Workplace Dramas, Ensemble Casts, 1990s Style - Donald Bogle61. This Is For Fighting, This Is For Fun: Camerawork and Gunplay in Reality-Based Crime Shows - Fred Turner62. Here Comes the Judge: The Dancing Itos and the Televisual Construction of the Enemy Asian Male - Brian Locke63. Ling Woo in Historical Context: The New Face of Asian American Stereotypes on Television - Chyng Feng Sun64. Jewish Women on Television: Too Jewish or Not Enough? - Joyce AntlerPart VII. The Internet65. The Titanic Sails On: Why the Internet Won't Sink the Media Giants - Robert McChesney66. " Where Do You Want to Go Today?" Cybernetic Tourism, the Internet, and Transnationality - Lisa Nakamura67. Television and the Internet - Ellen Seiter68. Dating on the Net: Teens and the Rise of "Pure" Relationships - Lynn Schofield Clark69. Staking Their Claim: Women, Electronic Networking, and Training in Asia - Rhona O. Bautista70. The Cherokee Indians and the Internet - Ellen L. Arnold and Darcy C. PlymireA List of Media Activist OrganizationsGlossaryBibliographyAuthor IndexSubject IndexAbout the EditorsAbout the Contributors。

西方后亚文化研究的理论走向马中红内容提要伯明翰大学“当代文化研究中心”的青年亚文化研究理论体系独树一帜,一度影响深远。

然而,随着后现代理论话语的盛行和互联网新媒体技术的普及,全球范围内的青年亚文化表现出了一系列新的文化症候。

新一代亚文化研究者在质疑和批评伯明翰学派的“阶级”、“抵抗”、“风格”等核心理论观点的基础上,提出了“生活方式”、“新族群”、“场景”等后亚文化研究理论关键词,旨在考察变化了的青年亚文化现象。

后亚文化研究的理论引起了进一步的争议,甚至有学者呼吁回归伯明翰青年亚文化学术理论体系。

关键词后亚文化研究生活方式新部落场景理论走向1964年,理查德·霍加特(Richard Hogart)在伯明翰大学建立了“当代文化研究中心”( Center for Contemporary Cultural Studies,CCCS)。

这一中心在其文化研究中发展了一种特别的青年亚文化理论体系,出版了大量研究成果。

20世纪80年代之后,由于文化研究自身的意识形态色彩过于浓厚,以及它们赖于建构理论体系的“阶级”正从我们眼前消失,加之西方后现代理论话语在文化研究领域的迅速扩张,新一代的亚文化研究者们开始质疑当代文化研究中心,并试图发展新的亚文化概念和理论,人们称其为英国青年亚文化的“第二波”,[1]或后亚文化研究;而其代表人物玛格尔顿(Muggleton)则将其命名为“后当代文化研究中心研究”。

②后亚文化研究的崛起和理论建构是青年亚文化研究值得关注的新动向。

一、从亚文化到后亚文化据资料考证,“亚文化”(sub-culture)的概念由美国社会学家弥尔顿·戈登(M.Gordon)首次提出并加以界定。

1947年,戈登发表了《亚文化概念及其应用》一文,其中将亚文化概念的出现溯源至1944年在纽约出版的《社会学词典》中的“culture-sub-area”,特指在一个大文化区域中那些具有独特文化特征的亚区域(sub-division),[2]并进一步发展这一概念。

图圈竺竺:竺竺!翌文章编号:1003-2398(2006)01—01lffq)6城市文化产业园区建设的区位因素分析王伟年”。

张平宇9(1东北师范大学城市与环境科学学院,长春130024;2.井冈山学院政法系,吉安3430093,中国科学院东北地理与农业生态研完所。

长春130012)ONLoC棚oNFACToRSFORCONSTRUCTINGURBANCULTURALINDI丁sTRU山PARKWANGWei—nian”,ZHANGPing-yu3以TheCollegeofUrbanandEnvh'onmenrScience,No'eastNonndUniversity,Chanchun130024,CMn2;2.TheDepartment.ofPohticsandLawJinggangstⅪnUniversity,}ian343009,China;互NortheastInstimt:eofGeographyandAgriculturalEcology,Cl哳eseAcademyofSciences,Changchun130012China)Abstract:Urbanculturalindustryoriginatesfromwesterndevelopedcountries,ithasdevelopedformorethanhalfcentury,anditsproportioninthenationaleconomyisbecominglargerandlarger.Comparedtothead-vancedurbanculturalindustryinthewest.urbanculturalindustryinChinastartedlate.Theurbanculturalin-dustrydidn’tdevelopveryfastuntiltheculturalindustryWaspromotedofficiallyinl992.However,inrecentyears.culturalindustriesinsomecitiesbegantoexerttheirimportantroleinpromotingtheculturalstatusofthecity,cultivatingagrowthpointofurbaneconomy,increasingemploymentrateandimprovingurbaneom—prehensivecompetitivenessWiththedevelopmentofChinesemodernization,urbanizationproblemsappear-ing.佃developurbanculturalindustrybecomesanimportantpofieyforimprovingeconomicstructureinChi-na.Thedevelopmentexperienceofurbanculturalindustryinwesterndevelopedcountriesdemonstratesthatanimportantwaytodevelopurbanculturalindustryistosetupculturalindustrialquarterordistrict.Somere-hatedresearchesontheculturalindustrialdistricthavebeenmadeabroad,however,thedomesticacademicfieldpayslittleattentiontoit,which,tosomeextent,affectsitshealthygrowth.Thispaperdiscussesthede—velopingreason,concept,connotation,typesoftheculturalindustriesdistrictandthepresentsituationinChi—na.Inthisfoundation,thispaperanalysesthelocationfactorsaffectingurbanculturalindustrialpark.Theyare(1)CulturalresourcesItisthefirstthingtobeconsideredinbuildingaculturalpark.Itindicatesthecul-ruralelementandculturalenvironmentoftheselectedzone.Thekeypointisthatwhetherthelocalculturalcharacteristicsiswellincluded.(窑)Institutionalfactor.ThesefactorsmostlyindicatetherelevantpoliciesofthestateaswelIasregionalculturalpolicy,culturalmanagementpattern,andlocalculturalindustrialpolicies.(妻)Informationtechnology.Thefuturedevelopmenttendencyofurbanculturalindustryandthenetworksys-ternjoiningtheenterprisesintheparkreliesonthemostadvancedinformationtechnology.@Intelligencere-sources.Theauthorsfinallypointouttheproblemsthatweshouldtakeintoconsiderationwhenselectingalo—cationforconstructinganur'bunculturalindustrypark.Keywords:urbanculturalindustry;culturalindustrypark;locationfactor提要:随着文化产业在我国的发展,城市文化产业园区的建设在各地日益兴起。