Stimulus Properties of PMMA Effect of Optical Isomers and Conformational Restriction

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:151.09 KB

- 文档页数:5

Heat-resistant PMMA photonic crystal films with bright structural colorBingtao Tang *,Cheng Wu,Tao Lin,Shufen ZhangState Key Laboratory of Fine Chemicals,Dalian University of Technology,Dalian 116024,PR Chinaa r t i c l e i n f oArticle history:Received 4July 2013Received in revised form 8August 2013Accepted 13August 2013Available online 26August 2013Keywords:Polymethylmethacrylate Methacrylic acid Photonic crystal film Structural color Heat-resistantGlass transition temperaturea b s t r a c tWeak heat resistance of polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA)photonic crystal films has been the major challenge for its applications in displays or paints.This paper presents heat-resistant PMMA photonic crystal films with a bright structural color that are produced by using a simple preparation strategy.In this strategy,the heat resistance was controlled and remarkably improved by introducing methacrylic acid as comonomer together with methyl methacrylate.The mechanism of improving heat resistance was characterized by using scanning electron microscopy and differential scanning calorimetry.Three-dimensional ordered structures are produced,directly forming photonic crystal films that are highly heat-resistant and have a bright structural color.These two properties are signi ficant for applications in displays or paints.Crown Copyright Ó2013Published by Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.1.IntroductionPhotonic crystals are one class of functional materials with a periodicity in dielectric constant,which can control and manipu-late light [1e 7].The ability of the crystals to control and manipulate light is important for their applications in full-color displays,paints,photonic paper,switches,modulators,and filters [8e 10].Among various technical applications,the direct conversion of light to color (structural color)has received signi ficant attention because of its unique characteristics such as energy conservation.Considering their unique characteristics,arti ficial structural color films made through colloidal crystallization self-assembly,dielectric layer stacking,and direct lithographic patterning have received consid-erable attention in recent years [11].In contrast to the expensive and non-scalable technologies of dielectric layer stacking and direct lithographic patterning,colloidal crystallization self-assembly is most frequently used in making photonic crystals because raw materials are easily obtained,and self-assembly is quite simple [11].Among the materials used for producing photonic crystals through colloidal crystallization self-assembly,polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA),which is weather resistant,durable,and chemically sta-ble,is of great signi ficance [12e 16].Sotomayor Torres et al.successfully used PMMA beads to obtain photonic crystal structural color films by drying the spread latex;the film typically appears iridescent in the visible range [17].Zhu et al.obtained P(NIPAm-co -MAA)hydrogel photonic crystal microparticles with inverse-opal structure by a combination of micro fluidic and templating methods,which can respond to pH simultaneously due to the ex-istence of MAA functional groups [18].Chen et al.loaded Cd 0.4Zn 0.6S nanocrystals on the surface of PS-co -PMAA microspheres.The ob-tained hybrids of integrating electronic con finement and photonic con finement,opened promising avenues in the design and con-struction of next-generation photoelectric devices based on pho-tonic crystals [19].Gu et al.prepared PMMA inverse opals,which could be stretched nearly 100%with diffraction peak blue-shifting across the whole visible spectrum [20].However,the tuning color was not reversible because of the plastic deformation of the PMMA sheet [21].Simultaneously,emulsion polymerization is a commonly used method of obtaining polymer microspheres from the free radical polymerization of vinyl monomers [22e 24].Copolymerization with functional monomers could achieve effec-tive modi fication of polymer,which is of great signi ficance to speci fic applications.Methacrylic acid (MAA)is typically used as comonomer to modify polymer such as polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA)and polystyrene (PSt).Robin et al.successfully encapsu-lated ZnO nanoparticles by P(MMA-MAA).MAA units of the ob-tained copolymer shell acted as a coupling agent,which then grafted onto polypropylene [25].*Corresponding author.Tel.:þ8641184986267;fax:þ8641184986264.E-mail address:tangbt@ (B.Tang).Contents lists available at ScienceDirectDyes and Pigmentsjournal h omepage:www.elsevier.co m/locate/dyepig0143-7208/$e see front matter Crown Copyright Ó2013Published by Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved./10.1016/j.dyepig.2013.08.012Dyes and Pigments 99(2013)1022e1028The persistence of photonic crystal structural color is crucial for its actual application in full-color displays,paints,and photonic paper.Once the periodic array is destroyed,the structural color will disappear.Therefore,the periodic arrays of photonic crystals should have high structural stability even under unstable environments.Among various external factors,temperature is very important because system temperature will increase as a result of the large thermal energy generated during solar radiation or laser irradiation [26e 28].However,PMMA has poor heat resistance because of its low glass transition temperature,which ranges from 40 C to 100 C [29e 31],which severely limits the application of PMMA photonic crystal films.In this report,heat-resistant photonic crystal structural color films were fabricated by assembling microspheres of methyl methacrylate (MMA)and methacrylic acid (MAA)through a vertical-lifting process.Three-dimensional ordered structures are achieved to form polymer crystal films that have a bright structural color.The introduction of MAA improves the heat resistance of photonic crystal films because copolymer has high spatial structure stability and temperature resistance [32].Therefore,heat-resistant PMMA structural color films that have a bright structural color are obtained.2.Experimental 2.1.MaterialsMMA,MAA,and potassium peroxydisulfate (initiator)were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Agent Company (Shanghai,China).All chemical reagents were used as received and without further puri fication.2.2.Preparation of PMMA microspheresThe following were gradually added to a 250ml three-necked flask:150ml deionized water,8.7g MMA,and a certain amount of MAA.After the mixture was heated to 80 C in a water bath under a N 2gas atmosphere,0.080g of initiator was added.Five hours later,the microsphere emulsion from the copolymerization of MAA and MMA was obtained.2.3.Preparation and characterization of photonic crystal films 25ml emulsion of PMMA spheres was poured into a 25ml beaker,and then the beaker was placed in a Coater with Heatment (SYDC-100H DPI,SAN-YAN Instrument Co.Ltd.,Shanghai).Glass slides were used as a substrate,and the pulling rate was set to 1m m/s.The whole process was carried out at 25 C.Glass slides were immersed in chromic acid lotion for 12h and washed carefully before being used.A Nanoparticle Size and Zeta Potential Measurement (Zetasizer Nano Series Nano-ZS90,Malvern,UK)were used to measure the hydrodynamic sizes and zeta potential of the particles.Optical photographs of the films were taken by using a Nikon digital camera.Scanning electron micrographs (SEM)were taken by using Nova NanoSEM 450to observe the surface microstructures of the photonic crystal films.All the samples were coated with gold beforeTable 1Effect of MAA concentration on particle size and size distribution of PMMA particles.MAA (wt%)Z-Ave (nm)a PDIZp (mV)D hD a 02862540.02À35.310.33142700.03À34.318.73483010.05À38.725.63803290.05À40.3aD h :Hydrodynamic size of these microspheres measured by nanoparticle size measurement.D a :Actual measured diameters from theSEM.Fig.1.SEM images of copolymer microspheres with varying MAA contents.(a)Pure PMMA,(b)10.3wt%,(c)18.7wt%,(d)25.6wt%.B.Tang et al./Dyes and Pigments 99(2013)1022e 10281023observation.The re flection spectra of the films,which ranged from 400nm to 800nm,were measured by using a Hitachi U-4100spectrophotometer.Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)was performed in a nitrogen atmosphere by using an American TA In-struments 910S DSC thermal analyzer from À20 C to 200 C at a heating rate of 5 C/min.FTIR spectroscopic analyses of the film samples were conducted in transmission mode by using a Thermo Scienti fic Nicolet 6700FTIR spectrometer.3.Results and discussionPMMA microspheres were prepared through the method of emulsion copolymerization.Table 1shows the effect of MAA con-tent on particle size and size distribution of PMMA particles.Monodisperse particles that have MAA content that varies between 0wt%and 25.6wt%are obtained.The hydrodynamic size of these microspheres increases monotonically from 286nm to 380nm.The actual measured diameters from the SEM results are 254,270,301,and 329nm,which are smaller than the hydrodynamic size.Poly-dispersity index (PDI)of the obtained microspheres ranges from 0.02to 0.05,and the corresponding zeta potential ranges from À34.3mV to À40.3mV.PDI and zeta potential results indicate that a stable monodispersed emulsion is prepared [33].After vertical-lifting assembly,the three-dimensional ordered structures were achieved.Fig.1shows the SEM images of the microstructure of photonic crystal films with varying MAAcontents.The uniformly-sized beads are arranged in an orderly array.The size of the microspheres increases along with the increasing amount of MAA.The three-dimensional ordered struc-ture can be further con firmed through the re flection spectra of polymer films in Fig.2.All films with 0,10.3,18.7,and 25.6wt%MAA show sharp re flectance peaks at wavelengths of 557,608,680,and 721nm.On the macro vision,structural color changes from green to red,as indicated in Fig.3.Bright structural colors are achieved because of an ordered structure (Fig.1).Compared with pure PMMA film,films with MAA show lower re flectance.It possibly results from the increase of PDI.As shown in Table 1,PDI increased from 0.02to 0.05when MAA was added.The increased PDI in-dicates that size distribution of microspheres turns wider and consequently leads to the reduction of re flectance.According to Bragg ’s law,the stop band and the color of a three-dimensional periodic structure can be explained by using the following equation:l ¼2d ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffin 2Àsin 2qq (1)where n is the effective refractive index of materials;d is the dis-tance between the crystalline planes in the (111)direction and is related to the polymer sphere diameter D by d ¼ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi2=3p D for theface-centered cubic (fcc)structure;and q ¼10 is the angle ofincident light.In addition,the effective refractive index n is deter-mined by the filling ratio (f )of the microparticles as follows:n ¼ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffin 2p f þn 2b ð1Àf Þq (2)where f ¼0.74is the filling ratio for the polymer in the fcc structure.n p and n b denote the refractive index of the polymer and back-ground materials,respectively.If the position of the stop band is within the visible range,the films display colors.The peak position of the stop band and the color of the crystal films depend on the relative filling ratio and the diameter of the polymer spheres.Here,n p ¼1.48and n b ¼n air ¼1,and the calculated peak positions of the stop bands for the photonic crystal films made of polymer spheres that are 254,270,301,and 329nm in diameter are 563,602,671,and 716nm,respectively.These values roughly match the experi-mental peak positions of 557,608,680,and 721nm,as shown in Fig.2.The FTIR spectrum can provide valuable information about the structure of the materials,which means that it can clearly reveal the copolymerization of MMA and MAA.For an accurate re flectionFig.2.Re flection spectra of films with varying MAA contents.(a)Pure PMMA,(b)10.3wt%,(c)18.7wt%,(d)25.6wt%.Fig.3.Photographs of polymer films with varying MAA contents.(a)Pure PMMA,(b)10.3wt%,(c)18.7wt%,(d)25.6wt%.B.Tang et al./Dyes and Pigments 99(2013)1022e 10281024of carboxy hydroxyl group in copolymers,we chose the paraffin paste method to avoid the interference of water contained in KBr. FTIR spectra for PMMA with varying MAA contents are shown in Fig.4a.The one on the top of Fig.4a is the curve of pure PMMA;it does not show the O e H bond at3253cmÀ1.This peak becomes stronger with increased MAA(Fig.4a).The broad peak at 2840cmÀ1to2970cmÀ1is caused by the paraffin.However, carbonyl group stretching peaks of carboxylic acid and carboxylic ester overlap completely at1730cmÀ1.To distinguish between the carboxy carbonyl group and the ester carbonyl group,we used Na2CO3as the basic reagent and tested the FTIR spectra after regulating the emulsion to pH9.At this moment,carboxylic acid exists in the form of carboxylic salt.Fig.4b shows the spectra,the one on the top is the curve of pure PMMA, and it displays only the C]O bond at1722cmÀ1.However,the copolymer(Fig.4b)also exhibits C]O stretches at1566cmÀ1, which indicates the presence of carboxylic salt.In summary,the O e H bond at3253cmÀ1in Fig.4a and the C]O bond at1566cmÀ1in Fig.4b proves the copolymerization of MMA with MAA.Heat resistance is an important property for polymers.To date, all reported photonic crystalfilms of PMMA have poor heat resis-tance because of their low glass transition temperature(T g).The DSC analysis(Fig.5a)shows that the glass transition temperatureof Fig.5.DSC curves(a)and the corresponding T g(b)of samples with varying MAAcontents.Fig.6.SEM images of PMMA photonic crystalfilms with18.7wt%MAA under various temperature.Rt:Roomtemperature.Fig.4.FTIR spectra of PMMA with varying MAA contents.(a)Spectra used infrared paraffin paste method,(b)Spectra after regulating pH.B.Tang et al./Dyes and Pigments99(2013)1022e10281025PMMA particles is improved when MAA is used.Pure PMMA has a heat flow change at 94.1 C,which corresponds to the T g of PMMA [34].Nevertheless,the photonic crystal films with 18.7wt%MAA shows a much higher T g at about 145 C (Fig.5a),which is higher than that of pure PMMA by about 50 C.The difference is ascribed to the con finement of intercalated PMMA chains [35]and demon-strates that the copolymer has better heat resistance than pure PMMA.As we can see in Fig.5b,a small amount of MMA can in-crease the T g of the polymer dramatically.Increasing the amount of MAA has little in fluence on T g when the copolymer contains more than 18.7wt%MAA.Photonic crystal structural colors are closely related to their periodicity order [36].Once the periodicity order is destroyed by heat,the structural color disappears.SEM was used toobserveFig.7.Photographs of photonic crystal films with 18.7wt%MAA under various temperature.Rt:Roomtemperature.Fig.8.SEM images of pure PMMA photonic crystal films under various temperature.Rt:Roomtemperature.Fig.9.Photographs of pure MMA photonic crystal films under various temperature.Rt:Room temperature.B.Tang et al./Dyes and Pigments 99(2013)1022e 10281026surface microstructure changes in these photonic crystal films during heating.As shown in Fig.6,the beads of PMMA photonic crystal films with 18.7wt%MAA are arranged uniformly with voids.However,as a result of the increasing temperature,microspheres deform,and voids shrink gradually after exceeding the T g of co-polymers.The effective refractive index decreases at the same time.As a result,the structural color fades,as indicated in Fig.7.When the temperature reaches 180 C,the voids disappear,which then results in the disappearance of color.Pure PMMA films show similar properties,while the microspheres ’deformation temperature is much lower.As we can see in Figs.8and 9,the microspheres deform into hexagons and the structural color of photonic crystal films disappears when the heating temperature reaches 100 pared with the pure PMMA films,copolymer photonic crystal films are more heat-resistant.The heat resistance of photonic crystal films can be identi fied by measuring the peak intensity at different temperatures.Fig.10shows the peak intensity of pure PMMA film and PMMA films with 10.3,18.7,and 25.6wt%MAA.For the pure PMMA film,the intensity decreases rapidly when the temperature increases to 90 C (Fig.10),and the intensity decreases to almost zero when the temperature is only 104 C.The re flectance peak intensity of the PMMA photonic crystal films with 18.7wt%MAA does not vary signi ficantly before the temperature increases to 160 C,which means that the close-packed structure is stable.Moreover,the in-tensity decreases dramatically to zero when the temperature is184 C,which can be attributed to the damage in the spherical structure.This decrease is due primarily to the reduced magnitude of the optical dielectric contrast,which is proportional to re flection intensity [37].Compared with the pure PMMA photonic crystal films,the heat resistance of the copolymer photonic crystal films that contain 18.7wt%MAA improves dramatically.The heat resistance of PMMA films was further proved by reversible temperature changes.Thermal cycling tests of PMMA photonic crystal films with 18.7wt%MAA were carried out,and the results of a 12-cycle test were shown in Fig.11.The samples are heated to 160 C every time,and peak intensity changes only little after 12cycles.The results also show that the films exhibit high heat resistance.In addition,the heat resistant PMMA film is man-ufactured in large-scale (Fig.12),which meets requirements for practical applications,especially serving as painting materials.4.ConclusionsIn summary,the heat resistance of PMMA films that have a bright structural color is dramatically improved by using meth-acrylic acid as a comonomer.The mechanism of improving the heat resistance of PMMA was investigated.PMMA photonic crystal films with 18.7wt%MAA could resist high temperatures up to 160 C.And the peak intensity changes only little after thermal cycling tests,which indicates that the films have high heat resistance.In addition,not only are the materials cheap and the preparation process simple and feasible,but the obtained PMMA photonic crystal films also display brilliant visual color under natural lighting conditions.This study offers a new approach for generating highly heat-resistant and brilliant photonic crystal films,which will accelerate their application in daily life.AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21276042),the National Science and Tech-nology Pillar Program (2013BAF08B06),Jiaogai Foundation of DUT (JGXM201224),Fundamental Research Funds for theCentralFig.10.Re flectance peak intensity of photonic crystal films with varying MAA contents at differenttemperature.Fig.11.Thermal cycling tests of PMMA photonic crystal films with 18.7wt%MAA.Fig.12.Photograph of PMMA photonic crystal films with 18.7wt%MAA manufactured in large-scale.B.Tang et al./Dyes and Pigments 99(2013)1022e 10281027Universities of China(DUT13LK35),and Program for Liaoning Excellent Talents in University(LJQ2013006).References[1]Kim SH,Lee SY,Yang SM,Yi GR.Self-assembled colloidal structures for pho-tonics.NPG Asia Mater2011;3:25e33.[2]Wu ZL,Gong JP.Hydrogels with self-assembling ordered structures and theirfunctions.NPG Asia Mater2011;3:57e64.[3]Joannopoulos JD,Villeneuve PR,Fan S.Photonic crystals.Solid State Commun1997;102:165e73.[4]González-Urbina L,Baert K,Kolaric B,Pérez-Moreno J,Clays K.Linear andnonlinear optical properties of colloidal photonic crystals.Chem Rev 2011;112:2268e85.[5]Hinterholzinger FM,Ranft A,Feckl JM,Ruhle B,Bein T,Lotsch BV.One-dimensional metal-organic framework photonic crystals used as platforms for vapor sorption.J Mater Chem2012;22:10356e62.[6]Chen YC,Geddes JB,Yin L,Wiltzius P,Braun PV.X-ray computed tomographyof holographically fabricated three-dimensional photonic crystals.Adv Mater 2012;24:2863e8.[7]Khunsin W,Amann A,Kocher-Oberlehner G,Romanov SG,Pullteap S,Seat HC,et al.Noise-assisted crystallization of opalfilms.Adv Funct Mater2012;22: 1812e21.[8]Arsenault AC,Puzzo DP,Manners I,Ozin GA.Photonic-crystal full-colourdisplays.Nat Photonics2007;1:468e72.[9]Campbell M,Sharp DN,Harrison MT,Denning RG,Turberfield AJ.Fabricationof photonic crystals for the visible spectrum by holographic lithography.Nature2000;404:53e6.[10]Han T,Liu YG,Wang Z,Wu Z,Wang S,Li S.Simultaneous temperature andforce measurement using Fabry-Perot interferometer and bandgap effect of a fluid-filled photonic crystalfiber.Opt Express2012;20:13320e5.[11]Kim H,Ge J,Kim J,Choi S,Lee H,Lee H,et al.Structural colour printing using amagnetically tunable and lithographicallyfixable photonic crystal.Nat Pho-tonics2009;3:534e40.[12]Ge J,Yin Y.Responsive photonic crystals.Angew Chem Int Ed2011;50:1492e522.[13]Shen W,Li M,Ye C,Jiang L,Song Y.Direct-writing colloidal photonic crystalmicrofluidic chips by inkjet printing for label-free protein b Chip 2012;12:3089e95.[14]Kimura T,Kawai T,Sakamoto Y.Magnetic orientation of poly(ethylene tere-phthalate).Polymer2000;41:809e12.[15]Pursiainen OL,Baumberg JJ,Winkler H,Viel B,Spahn P,Ruhl T.Nanoparticle-tuned structural color from polymer opals.Opt Express2007;15:9553e61.[16]Müller M,Zentel R,Maka T,Romanov SG,Sotomayor Torres CM.Dye-con-taining polymer beads as photonic crystals.Chem Mater2000;12:2508e12.[17]Müller M,Zentel R,Maka T,Romanov SG,Sotomayor Torres CM.Photonic crystalfilms with high refractive index contrast.Adv Mater2000;12:1499e503. [18]Wang J,Hu Y,Deng R,Liang R,Li W,Liu S,et al.Multiresponsive hydrogelphotonic crystal microparticles with inverse-opal ngmuir 2013;29:8825e34.[19]Yan L,Yu Z,Chen L,Wang C,Chen S.Controllable fabrication of nanocrystal-loaded photonic crystals with a polymerizable macromonomer via the CCTP ngmuir2010;26:10657e62.[20]Liu Z,Xie Z,Zhao X,Gu ZZ.Stretched photonic suspension array for label-freehigh-throughput assay.J Mater Chem2008;18:3309e12.[21]Zhao Y,Xie Z,Gu H,Zhu C,Gu Z.Bio-inspired variable structural color ma-terials.Chem Soc Rev2012;41:3297e317.[22]Van Gruijthuijsen K,Rufier C,Phou T,Obiols-Rabasa M,Stradner A.Light andneutron scattering study of PEG-oleate and its use in emulsion ngmuir2012;28:10381e8.[23]Han YK,Yih JN,Chang MY,Huang WY,Ho KS,Hsieh TH,et al.Facile synthesisof aqueous-dispersible nano-PEDOT:PSS-co-MA core/shell colloids through spray emulsion polymerization.Macromol Chem Phys2011;212:361e6. [24]Xia H,Wang Q,Qiu G.Polymer-encapsulated carbon nanotubes preparedthrough ultrasonically initiated in situ emulsion polymerization.Chem Mater 2003;15:3879e86.[25]De Rancourt Y,Couturaud B,Mas A,Robin JJ.Synthesis of antibacterial sur-faces by plasma grafting of zinc oxide based nanocomposites onto poly-propylene.J Colloid Interface Sci2013;402:320e6.[26]Synnefa A,Santamouris M,Livada I.A study of the thermal performance ofreflective coatings for the urban environment.Sol Energy2006;80:968e81.[27]Takebayashi H,Moriyama M.Surface heat budget on green roof and highreflection roof for mitigation of urban heat island.Build Environ2007;42: 2971e9.[28]Ihara I,Yamada H,Takahashi M.Two-dimensional monitoring of surfacetemperature distribution of a heated material by laser-ultrasound scanning.J Phys Conf Ser2011;278:012022.[29]Kopesky ET,McKinley GH,Cohen RE.Toughened poly(methyl methacrylate)nanocomposites by incorporating polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxanes.Polymer2006;47:299e309.[30]Ash BJ,Siegel RW,Schadler LS.Glass-transition temperature behavior ofalumina/PMMA nanocomposites.J Polym Sci Part B Polym Phys2004;42: 4371e83.[31]Grohens Y,Brogly M,Labbe C,David MO,Schultz J.Glass transition ofstereoregular poly(methyl methacrylate)at ngmuir1998;14: 2929e32.[32]Yu GU,Dy JT,Enriquez EP.Opacity of P(MMA-MAA)-PMMA composite latexsystem with varying MAA concentration.Philipp J Sci2011;140:221e30. [33]Wong S,Kitaev V,Ozin GA.Colloidal crystalfilms:advances in universalityand perfection.J Am Chem Soc2003;125:15589e98.[34]Zhang Y,Wang X,Liu Y,Song S,Liu D.Highly transparent bulk PMMA/ZnOnanocomposites with bright visible luminescence and efficient UV-shielding capability.J Mater Chem2012;22:11971e7.[35]Matsubara K,Watanabe M,Takeoka Y.A thermally adjustable multicolorphotochromic hydrogel.Angew Chem Int Ed2007;46:1688e92.[36]Seago AE,Brady P,Vigneron JP,Schultz TD.Gold bugs and beyond:a review ofiridescence and structural colour mechanisms in beetles(Coleoptera).J R Soc Interface2009;6:S165e84.[37]Bertone JF,Jiang P,Hwang KS,Mittleman DM,Colvin VL.Thickness depen-dence of the optical properties of ordered silica-air and air-polymer photonic crystals.Phys Rev Lett1999;83:300e3.B.Tang et al./Dyes and Pigments99(2013)1022e1028 1028。

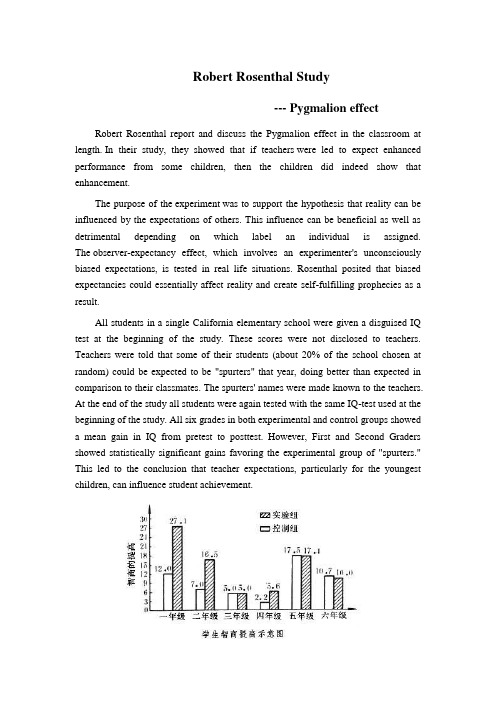

Robert Rosenthal Study--- Pygmalion effectRobert Rosenthal report and discuss the Pygmalion effect in the classroom at length. In their study, they showed that if teachers were led to expect enhanced performance from some children, then the children did indeed show that enhancement.The purpose of the experiment was to support the hypothesis that reality can be influenced by the expectations of others. This influence can be beneficial as well as detrimental depending on which label an individual is assigned. The observer-expectancy effect, which involves an experimenter's unconsciously biased expectations, is tested in real life situations. Rosenthal posited that biased expectancies could essentially affect reality and create self-fulfilling prophecies as a result.All students in a single California elementary school were given a disguised IQ test at the beginning of the study. These scores were not disclosed to teachers. Teachers were told that some of their students (about 20% of the school chosen at random) could be expected to be "spurters" that year, doing better than expected in comparison to their classmates. The spurters' names were made known to the teachers. At the end of the study all students were again tested with the same IQ-test used at the beginning of the study. All six grades in both experimental and control groups showed a mean gain in IQ from pretest to posttest. However, First and Second Graders showed statistically significant gains favoring the experimental group of "spurters." This led to the conclusion that teacher expectations, particularly for the youngest children, can influence student achievement.。

Crystalline structures in ultrathin poly(ethylene oxide)/poly(methylmethacrylate)blend filmsMingtai Wang *,Hans-Georg Braun *,Evelyn MeyerInstitute of Polymer Research Dresden,Hohe Strasse 6,D-01069Dresden,Germany Received 26May 2003;received in revised form 2June 2003;accepted 10June 2003AbstractAmorphous poly(ethylene oxide)/poly(methyl methacrylate)(PEO/PMMA)blend films in extremely constrained states are meta-stable and phase separation of fractal-like branched patterns happens in them due to heterogeneously nucleated PEO crystallization by diffusion-limited aggregation.The crystalline branches are viewed flat-on with PEO chains oriented normal to the substrate surface,upon increasing PMMA content the branch width remains invariant but thickness increases.It is revealed that PMMA imposes different effects on PEO crystallization,i.e.the length and thickness of branches,depending on the film composition.q 2003Elsevier Science Ltd.All rights reserved.Keywords:Crystallization;Poly(ethylene oxide);Surface pattern1.IntroductionEven though polymer crystallization has been exten-sively studied during the past decades [1,2],the crystal-lization in ultrathin films is a new topic in this field.Special enthalpic and entropic factors at polymer/substrate interface cause the organization of polymer chains in ultrathin films to deviate from their bulk states [3–6],and substrate adsorption effect,due to which polymer chains form stable loops dangling in the direction perpendicular to the substrate surface,reduces the thermodynamic potential of hetero-geneous nucleation for crystallization [7].Studying the crystallization in ultrathin polymer films has offered a possibility to reveal polymer chain organization during crystallization in real space [8–15].However,observation of crystalline morphology has mainly been done in ultrathin films containing only one polymer,and branched structures due to non-equilibrium crystallization by a diffusion-limited aggregation (DLA)process are always the case in the films of a thickness less than 10nm,as shown by the terrace structures with fingers [8,9],the finger-like [10–13]and fractal-like [15]patterns.In forming these structures,heterogeneous nucleation is necessary and polymer chains fold without influence of other polymers and by a stem length of 7–13nm.In this report we show the crystalline structures in ultrathin poly(ethylene oxide)/poly(methyl methacrylate)(PEO/PMMA)blend films and the effects on PEO crystallization imposed by PMMA.2.ExperimentalPolyethylene glycol standard (M w ¼6000;M w =M n ¼1:03)from Fluka and PMMA standard (M w ¼4200;M w =M n ¼1:06)from Polymer Standards Services (PSS,Germany)were used as received to prepare PEO/PMMA blend films.The radius of gyration,R g ;of a polymer chain is calculated by R g ¼ðNb 2=6Þ1=2;where N is the degree of polymerization and b the average statistical segment length.For b PMMA ¼0:69nm [16],the R g of the PMMA chain is 1.77nm.According to the data in literature [17],the b PEO and R g of the PEO chain are calculated to be 0.70and 3.30nm,respectively.Au films of 100nm thickness were prepared by thermal evaporation (rate 0.1nm/s)of gold on the glass slides primed with a Cr adhesive layer of 3nm thickness.PEO/PMMA blend films were dip-coated on the Au films from chloroform solutions (totally 1mg/ml)at an average lifting rate of 1.90mm/s.The coated polymer layers (given a refractive index of 1.5)0032-3861/03/$-see front matter q 2003Elsevier Science Ltd.All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/S0032-3861(03)00492-0Polymer 44(2003)5015–5021/locate/polymer*Corresponding authors.Tel.:þ49-351-4658633;fax:þ49-351-4658284.E-mail addresses:mingtaiwang@ (M.Wang),braun@ipfdd.de (H.G.Braun).had a thicknessðDÞof2–3.0nm within the tested composition range(0–50%PMMA,by weight).For D# R g of the longest component(PEO),thefilms can be defined as extremely constrained two-dimensional ones[16,18].To provide defined areas for studying crystallization by means of scanning electron microscopy(SEM)and atomic force microscopy(AFM),an newly-coatedfilm wasfirst scratched once with a razor blade after drying in the air for 15min,and then put immediately into a vacuum(in SEM sample chamber,ca.1026h Pa)to crystallize for about17h. For grazing incidence reflection infrared(GIR-IR)spec-troscopy,thefilms that had been dried in the air for15min were crystallized in the vacuum for24h without scratching. The temperature in the vacuum chamber was estimated by ambient temperatures to be21–228C.In vacuum condition the moisture influence on crystallization was eliminated.Film thickness was measured on an ELX-02C ellips-ometer(DRE GmbH,Germany;He–Ne laser source 632.8nm,708angle of incidence)in15–20min after coating when thefilm was still amorphous.GIR-IR spectra were recorded in vacuum on an IFS66V/S spectrometer (Bruker Co.),using a grazing incidence external reflection stage(from SPECAC,incident angle808C)at a resolution of4cm21and1000scans and a bare Aufilm as reference. Optical microscopy(OM)observation was done on a light microscope(Zeiss/Sis,Germany)in dark-field mode in ambient conditions.SEM and AFM studies of the samples were performed immediately after crystallization,as described previously[15].3.ResultsAs a typical blend system containing amorphous and semi-crystalline components,PEO/PMMA blend in bulk state has been studied by different means,such as differential scanning calorimetry(DSC)[19],nuclear magnetic resonance(NMR)[20],small-angle X-ray scatter-ing(SAXS)and small-angle neutron scattering(SANS)[21] and microscopy[22].In general,PEO and PMMA are miscible in melt and amorphous states resulting in a single concentration-dependent glass transition[23],addition of PMMA reduces the crystal growth rate[24,25]and crystal-linity[22,26]of PEO.The growth and melting of crystal lamellae of PEO spherulites in thin PEO/PMMAfilms have been revealed by hot-stage AFM[27].Recently,Ferreiro and co-workers[28]reported that the crystalline mor-phology in thin PEO/PMMAfilms(ca.200nm thick)can be tuned byfilm composition to get circular spherulites(50–100%PEO),seaweed morphology(40–50%PEO),sym-metric dendrites(30–40%PEO)and fractal structures(15–25%PEO).They also presented the growth dynamics of the symmetric dendrites with a focus on their growth pulsations [29],but how thefilm morphology is tuned by adding PMMA still remains unclear.In spite of the above extensive studies,we,to our knowledge,are still lacking the observation on the crystalline morphology in ultrathin PEO/PMMAfilms.3.1.SEM and OM observationsAfter crystallization in vacuum for several hours(e.g. 17–18h),the blendfilms are decorated by branched structures stemming from the scratch line(Fig.1).The branched structures clearly resemble the fractals formed in electrodeposition[30,31]and bacterial growth[32].Fractal formation proceeds theoretically by DLA process[33,34]. Crystalline structures reminiscent of DLA process have been observed in ultrathin PEOfilms,for example,the finger-like pattern in PEO monolayers[10,11].Reasonably, the fractal-like structures here are related to PEO crystal-lization in the blendfilms by DLA process.Note that SEM observations of the freshfilms showed that the PEO/PMMA films were homogeneous,but the pure PEOfilm was dispersed with some PEO dots(ca.1m m in diameter and6–7nm in height)that should be due to de-wetting of PEO on the substrate duringfilm formation because of the weak interaction between the Au surface and PEO[35];the non-scratchedfilms were not found branched structures for at least1h when kept in the vacuum.The branch growth depends strongly onfilm composition (Fig.1).Generally,both main branches and sub-branches became shorter with PMMA content.The branches were very long in90/10(¼PEO/PMMA)film,and the substrate surface was covered mainly by the branches stemming from the scratch line(Fig.1(b));but the branches in75/25film were much shorter than those in90/10film and a large structureless area appeared in front of the branches(Fig. 1(c)).Further increasing PMMA content to40%,the branches along the scratch line became much shorter and a much larger structureless areas resulted in front of them (Fig.1(d)).In PEOfilm,the branches stemming from PEO dots were much longer than these from the scratch line,the substrate surface was mainly covered by the branches nucleated by PEO dots which should crystallize prior to the branch growth because of their higher thickness[11].The scratch line was created for two purposes,to act as heterogeneous nucleation for crystallization and to provided defined areas for studying crystallization.Under an optical microscope,90/10film was observed to show,in about 3min after scratching with a needle(228C,33%relative humidity),the contrast change in the zones along the scratch line,indicating the starting of crystallization;however,we didn’tfind evidently the crystal growth in75/25film for 25min after scratching.Therefore,the branched structures here were not a direct result of scratching[36],and the scratch line acted as a surface defect to nucleate polymer chains.In the case of50/50film,where the branches were normally very short,a fortuitous long branched structure was found stemming from the scratch line,as shown in Fig.2.SEM revealed that the long structure grew actually alonga defect zone on the Au surface,which shows that theM.Wang et al./Polymer44(2003)5015–5021 5016structureless areas in front of the branches along the scratch line (Figs.1(d)and 2)consist of amorphous PMMA and PEO but the crystallization in them needs further hetero-geneous nucleation.The crystallization in the films (Fig.1)did take place in vacuum.On one hand,the time interval between the finish of scratching and the start of SEM vacuumization was very short (within ca.1min).On the other hand,if branch growth had finished before putting the film into the vacuum the branches should mainly stem from the scratch line and those nucleated by PEO dots should be much shorter in PEO film (Fig.1(a)).3.2.GIR-IR measurementsFig.3shows the GIR-IR spectra of the ultrathin films.Detailed assignments of IR vibrations of PEO [35,37]and PMMA [38]have been described by pared with the isotropic spectrum of bulk PMMA,the stretching band of methacrylate side group at 1100–1300cm 21is greatly enhanced relative to the C y O vibration at 1734cm 21in the ultrathin PMMA film,indicating that the film has more methoxy groups oriented normal to the Au surface than carbonyl groups and that PMMA is physically adsorbed onto the substrate due to interaction of the polarmethoxyFig.1.SEM images of the fractal-like structures in ultrathin PEO/PMMA films of different blend compositions,(a)100/0,(b)90/10,(c)75/25and (d)60/40.The scale bar of 10m m is for all images.The samples were crystallized for 17h.Fig.2.A SEM image of the fractal-like structures in ultrathin PEO/PMMA film of 50/50composition.The branches along the scratch line are normally very short in this sample (Inset).This image mainly shows a long branched structure stemming from the scratch line,which grew actually along a defect zone.The sample was crystallized for 17.5h.Fig.3.GIR-IR spectra of the ultrathin films crystallized for 24h.The traces correspond to the weight ratios of PEO/PMMA marked on the curves.SEM verified that the crystallization in blend films started from surface defects (e.g.dust particles).M.Wang et al./Polymer 44(2003)5015–50215017and carbonyl groups with the Au surface[38].Reasonably, PMMA prevented PEO from de-wetting during the co-deposition of them from solution[35],resulting in homogeneous blendfilms.The spectra of PEO at different temperatures[35,37] show that the intensity of the CH2wagging vibration of PEO at1342cm21is sensitive to the conformation order,which can be used to evaluate crystallization process[26].With respect to the CH2stretching vibration at around2888cm21 that is mainly attributed to PEO component,the change in the intensity of PEO band at1342cm21with PMMA content indicates that a higher PMMA content leads to a lower crystallinity of PEO in thefilm.As PMMA content is $40%the blendfilms are mainly amorphous.Only bands with transition dipole moments parallel(k)to PEO chain axis(1342,1242,1107and963cm21)[35,37] are intensively observed in the GIR-IR spectra of ultrathin PEO and90/10films.In the spectrum of75/25film,the vibrations of k bands are still evident while they are much weaker than the90/10and PEO cases.In thefilms with PMMA content$40%the vibration signals of PEO crystals are very weak(1342cm21)and non-evident(963cm21)for the crystal branches in them were too short to be easily detected by the GIR-IR scans,but the orientation of the crystallized PEO chains in them can be reasonably inferred by the results of the90/10and75/25films since thefilms crystallized in the same condition.Thus,the PEO chains in the crystals formed in the studiedfilms orient perpendicular to substrate surface and the branches are viewedflat-on, because in GIR-IR measurements only the transition dipole moment components normal to substrate surface can be observed.3.3.AFM resultsAFM measurements were performed to get the branch thickness,as shown in Fig.4.In the PEOfilm,the branches had a homogeneous thickness of8^1nm(Fig.4(a)). However,the branch thickness in the blendfilms verified with PMMA content,namely,4^1nm in90/10film(Fig. 4(b)),6^1nm in75/25film(Fig.4(c))and10^1nm in 60/40and50/50films(Fig.4(d)).For PMMA phases may segregate beside the branches(refer to latter discussion),the actual branch thickness may be somewhat larger than the measured data in the blendfilms,particularly in those containing a high PMMA content.Notice that the branches in60/40and50/50films had a similar thickness by the AFM data(Fig.4(d)),but the branches in the50/50film may actually be thicker than those in60/40film because more PMMA can segregate beside the branches in50/50film.As the branch growth mainly proceeds laterally and the PEO chains within the crystals take exclusively a confor-mation with chain axes perpendicular to substrate surface, one branch formed in thefilms studied here is reasonably a crystal lamella viewedflat-on and its thickness is related to the stem length of PEO chain folds within it.In pure PEO film the thickness of such branches is a direct measure of chain folding states[11,12,15].The thickness of8^1nm (Fig.4(a))infers that PEO chains fold4times when without influence of PMMA,as the length L of the fully extended crystalline PEO chain is37nm according to L¼ðM PEOn=M EO nÞ£0:2783nm[39].Even though the exact folding states of PEO chains in blendfilms,particularly as afilm contains a high PMMA content,are hard to obtain from the AFM data(Fig.4(c)and(d))because of the possible discrepancy between the actual and measured values of the branch thickness,the tendency towards higher branches when increasing PMMA content will not be altered.Therefore,from the composition dependence of branch thickness one would get an evaluation of PMMA influences on the organization of PEO chains during crystallization.4.DiscussionThe amorphous PEO/PMMA blendfilms are obtained by constrained geometry and only meta-stable,phase separ-ation of fractal-like branched patterns happens in them due to heterogeneously nucleated PEO crystallization by DLA process.The PEO chains in the crystals come from the amorphous blend areas ahead of them[10–12,15],where PEO and PMMA are mixed.Results show that increasing PMMA content to more than10%leads to a remarkable retardation effect of PMMA on the branch length,and only the PEO chains near the heterogeneous nucleation sites in films with PMMA content$40%can crystallize so that the films are mainly amorphous(Figs.1–3).In bulk state,the blends with PMMA content higher than,70%are completely amorphous[19,22,40].This indicates that the retardation effect of PMMA on PEO crystallization is dramatically enhanced by constrained geometry in the ultrathinfilms.Crystallization in the blendfilms involves the general features revealed in ultrathin PEO[10–12,15]and other polymer[8,9,14]films,namely,requiring necessary hetero-geneous nucleation,chain orientation normal to substrate surface and branched structures related to DLA process. Therefore,the crystal growth in the blendfilms obeys the basic principles in ultrathin polymerfilms,for example,the growth process is controlled by chain diffusion.It is believed that the retardation effect of PMMA on the branch growth is to reduce the transport property(mobility)of PEO chains in our cases,because upon increasing PMMA the mobility of PEO chains can be strongly reduced[20]and the system will become more rigid[22].SEM and AFM provide detailed structural information on the crystals.These data contain several interesting features.First,as PMMA content was changed from10to 40%,the branch thickness increased strikingly from4^1 to10^1nm.Second,the branches in90/10film were much thinner than those in PEOfilm.Finally,the branchM.Wang et al./Polymer44(2003)5015–5021 5018width (ca.0.20m m)in the blend films was independent of PEO/PMMA ratio,but smaller than that of the branches formed in the PEO film.As mentioned previously,the branch thickness is directly related to the chain folding during crystallization and can give an access to the information on the organization of PEO chains under PMMA influence.The thickness of the crystalline branches is determined by the kinetics of chain deposition at crystal growth fronts in diffusion-controlled growth process [11,12,15].A lowered chain deposition rate,which was achieved by evaluating crystallization temperature ðT c Þ[11]and by reducing the polymer concentration in diffusion field [15],has been proved in ultrathin PEO films to favor the growth of thicker branches.Reiter and Sommer [11,12]showed that the thickness of crystal lamellae increases with crystallization temperature.They argued that at a high deposition rate (large undercooling)the molecules attached to the crystal have less time to stretch out and are thus in a state of relatively low internal chain order (folded state);in contrast,if the crystals grow slowly,the attached molecules have more time to relax towards the fully extended form of lowest free energy by rearrangements at the crystal surface.Our previous results [15]showed that,as a result of the reduction of chain availability in the diffusion field,the chain deposition rate (or probability)at crystal growth fronts becomes small and the deposited polymer chains have a high probability to rearrange themselves to a state near equilibrium.In our opinion,the increase in branch thickness with PMMA content in the blend films results from the lowered chain deposition rate by adding PMMA (Fig.4(b)–(d)).PMMA has a high glass transition temperature ðT g Þ;but PEO have a low one.As a consequence of mixing thesetwoFig.4.AFM images of the fractal-like structures in ultrathin PEO/PMMA films of different blend compositions,(a)100/0,(b)90/10,(c)75/25(c)and (d)60/40.The inset to (d)is for 50/50film.The samples were crystallized for 17h and measured by means of non-contact AFM immediately after being taken out of the vacuum chamber;the scanned areas were near scratch line.All the branches were nucleated by the scratch lines,except for those in the left side of image (a)that were nucleated by a PEO dot.M.Wang et al./Polymer 44(2003)5015–50215019miscible polymers,the amorphous phase T g increases as theconcentration of PMMA increases[23],resulting in a morerigid crystallization system with a more reduced mobility ofPEO chains.The reduction of PEO chain mobility willinevitably lower the chain deposition rate at crystal growthfronts,leading to an easier relaxation of the deposited chainstowards the extended state and further higher branches asdescribed elsewhere[11,15].In a blend consisting of a semi-crystalline polymer andan amorphous one the equilibrium melting pointðT m80Þdepends on composition,increasing amorphous concen-tration will depress T m80[24,41,42].One question may arise,concerning whether the origin of the increase in branchthickness with PMMA content comes from the decrease inthe effective undercooling D TðD T¼T m802T cÞat whichcrystallization occurs.T m80in PEO/PMMA blends decreaseswith increase of PMMA content in the blends[24,41],butthe decreases is slight and only a maximum depression ofca.2.58C was observed[24].In spite of the depression ofT m80;moreover,the crystalline thickness in PEO/PMMA blends is independent of composition[21,41],but increaseswith T c:The equilibrium melting pointðT o mÞof the pure PEO used in this study was ca.648C,which was obtained byreferring to the data of a similar PEO(M w¼6000;M w=M n¼1:03;from Fluka Co.)in literature[24].There is no reason to believe that the increase in branch thickness with increasing PMMA content in our cases results mainly from the decrease in the effective undercooling,of which the contribution would be very faint if it could not be completely ruled out because the T c in our experiments was about428C below the T o m of the pure PEO.Interestingly,the branches in90/10film were muchthinner than those in PEOfilm(Fig.4(a)and(b)),whichshould not be caused by the PMMA segregating beside thebranches in the blendfilm because PMMA content wasrather low.A slow deposition rate of PEO chains at growthfronts favors the formation of higher branches,whereas afast deposition rate will result in thinner branches[11,15].Itis clear that the crystallization was accelerated in90/10filmas compared with that in PEOfilm.The crystal growth wasalso found to be enhanced in90/10blend of PEO/isotactic-PMMA(i-PMMA)when compared to the pure PEO,ratherthan being disrupted,this phenomenon was considered torelate to the immiscibility between PEO and i-PMMA[25].Therefore,two competitive effects may be imposed byPMMA on PEO crystallization depending on thefilmcomposition,to retard the crystallization by reducing themobility of PEO chains and to accelerate the crystallizationby probably de-mixing,where the latter effect is dominantas PMMA concentration is low but the former one will beenhanced by increasing PMMA content(Fig.4).As shown previously[15],a surface-tension effect,which favors the minimized interface area of crystal growthfronts,is coming into effect with the reduction in depositionrate of chains and the deposited chains will occupy a highestnumber of nearest neighbors at the growth fronts.With this consideration,one might expect a broadening of branches as the deposition rate reduces with increasing PMMA content. However,the branch width(ca.0.20m m)in the blendfilms is independent offilm composition and generally smaller than that in PEOfilm(Figs.1and4).No external factors could impose influences on the branch width in our experiments,except for the presence of PMMA in the system.On the other hand,the width difference between the branches in the blend and PEOfilms could not result from the two competitive effects imposed by PMMA in that the branch width did not changed with increasing PMMA content.The possible origin of the small and constant branch width in blendfilms lies in the laterally excluded PMMA phases from the crystals,which can be rationalized by the fact that the‘impurities’(PMMA)segregate away from the growth front and between the growing lamellae during the growth of PEO spherulites in thin PEO/PMMA films[27]and by the invariant crystalline lamellar thickness and increasing small-angle long period of crystalline phases with addition of PMMA[21,41].The deposition of PEO chains at the side faces of branches can be prevented by the excluded PMMA phases,but this will not be the case in the PEOfilm.5.ConclusionThe results presented in this study show the crystalline morphology in ultrathin PEO/PMMA blendfilms.The blendfilms in extremely constrained states are amorphous and meta-stable,and phase separation in them follows a fractal-like branched pattern due to heterogeneously nucleated PEO crystallization by DLA process.The crystal branches are viewedflat-on with polymer chains oriented normal to the substrate surface;the PEO chains in the crystalline branches come from the amorphous blend areas ahead of them.The branch width in blendfilms is independent of thefilm composition,which relates to the laterally excluded PMMA phases from the crystals.The presence of PMMA influences strikingly the branch length and thickness by imposing two competitive effects on the PEO crystallization,to accelerate and to retard the crystal-lization,depending on thefilm composition.The acceler-ated crystallization,probably by de-mixing between PEO and PMMA,leads to thinner and longer crystal branches; the retardation effect of PMMA,which results in thicker and shorter crystal branches,is attributed to reducing the mobility of PEO chains in the system. AcknowledgementsThe authors thank the DFG for supporting this work (priority program‘Wetting and structure formation at surfaces’).M.Wang acknowledges the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation for a research fellowship.M.Wang et al./Polymer44(2003)5015–5021 5020References[1]Bassett BC.Principles of polymer morphology.Cambridge:Cam-bridge University Press;1981.[2]Strobl G.The physics of polymers.Berlin:Springer;1996.[3]Despotopoulou MM,Miller RD,Rabolt JF,Frank CW.J Polym Sci:Part B:Polym Phys1996;34:2335–49.[4]Despotopoulou MM,Frank CW,Miller RD,Rabolt JF.Macromol-ecules1996;29:5797–804.[5]Frank CW,Rao V,Despotopoulou MM,Pease RFW,Hinsberg WD,Miller RD,Rabolt JF.Science1996;273:912–5.[6]Theodotou DN.Molecular modeling of polymer surfaces andpolymer/solid interfaces.In:Sanchez IC,editor.Physics of polymer surfaces and interfaces.Butterworth-Heinemann:Boston;1992.p.139–62.[7]Ebengou RH.J Polym Sci:Part B:Polym Phys1997;35:1333–8.[8]Sakai Y,Imai M,Kaji K,Tsuji M.J Cryst Growth1999;203:244–54.[9]Sakai Y,Imai M,Kaji K,Tsuji M.Macromolecules1996;29:8830–4.[10]Reiter G,Sommer JU.Phys Rev Lett1998;80:3771–4.[11]Reiter G,Sommer JU.J Chem Phys2000;112:4376–83.[12]Sommer JU,Reiter G.J Chem Phys2000;112:4384–93.[13]Reiter G,Castelein G,Sommer JU.Phys Rev Lett2001;86:5918–21.[14]Zhang F,Liu J,Huang H,Du B,He T.Eur Phys J E2002;8:289–97.[15]Wang M,Braun HG,Meyer E.Macromol Rapid Commun2002;23:853–8.[16]Tanaka K,Takahara A,Kajiyama T.Macromolecules1996;29:3232–9.[17]Chen EQ,Lee SW,Zhang A,Moon BS,Mann I,Harris FW,ChengSZD,Hsiao BS,Yeh F,von Merrewell E,Grubb DT.Macromolecules 1999;32:4784–93.[18]Tanaka K,Yoon JS,Takahara A,Kajiyama T.Macromolecules1995;28:934–8.[19]Liau WB,Chang CF.J Appl Polym Sci2000;76:1627–36.[20]Schantz S.Macromolecules1997;30:1419–25.[21]Russell TP,Ito H,Wignall GD.Macromolecules1988;21:1703–9.[22]Martuscelli E,Silvestre C,Addonizio ML,Amelino L.MakromolChem1986;187:1557–71.[23]Liberman SA,Gomes AS,Macchi EM.J Polym Sci:Polym Chem Ed1984;22:2809–15.[24]Alfonso GC,Russell TP.Macromolecules1986;19:1143–52.[25]John E,Ree T.J Polym Sci:Part A:Polym Chem1990;28:385–98.[26]Li X,Hsu SL.J Polym Sci:Polym Phys Ed1984;22:1331–42.[27]Pearce R,Vancso GJ.J Polym Sci:Part B:Polym Phys1998;36:2643–51.[28]Ferreiro V,Douglas JF,Warren JA,Karim A.Phys Rev E2002;65:042802.[29]Ferreiro V,Douglas JF,Warren J,Karim A.Phys Rev E2002;65:051606.[30]Matsushita M,Sano M,Hayakawa Y,Honjo H,Sawada Y.Phys RevLett1984;53:286–9.[31]Matsushita M,Hayakawa Y,Sawada Y.Phys Rev A1985;32:3814–6.[32]Ben-Jacob E.Contemporary Phys1997;38:205–41.[33]Witten TA,Sander LM.Phys Rev Lett1981;47:1400–3.[34]Sander LM.Nature1986;322:789–93.[35]Hoffmann CL,Rabolt JF.Macromolecules1996;29:2543–7.[36]Hobbs JK,Humphris ADL,Miles MJ.Macromolecules2001;34:5508–19.[37]Yoshihara T,Tadokoro H,Murahashi S.J Chem Phys1964;41:2902–11.[38]Lenk TJ,Hallmark VM,Rabolt JF,Ha¨ussling L,Ringsdorf H.Macromolecules1993;26:1230–7.[39]Kovacs AJ,Straupe C.J Cryst Growth1980;48:210–26.[40]Parizel N,Laupreˆtre F,Monnerie L.Polymer1997;38:3719–25.[41]Cimmino S,Pace ED,Martuscelli E,Silvestre C.Makromol Chem1990;191:2447–54.[42]Rim PB,Runt JP.Macromolecules1984;17:1520–6.M.Wang et al./Polymer44(2003)5015–50215021。

植物病原体检测和主机防御NBS-LRR蛋白Brody J DeYoung and Roger W InnesDepartment of Biology, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana 47405, USA.摘要核苷酸结合位点富含亮氨酸重复(NBS-LRR)家族属于植物蛋白用于病原体检测。

像哺乳动物的NOD- LRR蛋白'传感器'检测细胞内保守的病原相关分子模式,植物NBS-LRR蛋白检测病原体相关的蛋白质,最经常的效应分子负责的病原体毒力。

许多致病蛋白质的检测通过植物NBS-LRR蛋白间接从修改毒性蛋白造成宿主上的靶蛋白。

然而,一些NBS-LRR蛋白质直接结合病原菌的蛋白质。

以修改宿主蛋白或病原体的蛋白在植物NBS-LRR蛋白中的氨基末端和LRR结构域的构象变化。

这种构象的改变被认为是促进促进NBS结构域中ADP向ATP的转化,这样激活下游信号,由一个未知机制,导致病原体的抵抗作用。

植物缺乏脊椎动物适应性免疫靠什么来应对病原体。

至成功检测和抵御病原体,植物必须完全依赖于稳定的编码基因在基因组中。

虽然病原体检测的确切机制不同,植物,如动物,使用两个不同的防御系统,以识别和应对病原体的挑战,病原相关分子模式(PAMPS),如细菌鞭毛确认脂多糖和真菌疫的纤维素结合结构激发蛋白质,由植物跨膜受体,激活基础防御,第一道防线病原体想起先天免疫在脊椎动物中。

在植物和动物据推测生物的“军备竞赛”正在发生,使病原体已取得PAMP触发免疫逃避机制,通过不断变化的效应修改状态在宿主细胞的分子,从而绕过或破坏的第一行防线。

植物进化反击,蛋白质,检测特异性效应分子,一个机制,称为“效应触发免疫到第二行的金额防线。

植物效应触发免疫更像是哺乳动物适应性免疫该病原体的效应,而不是保守的元素,如的PAMPs,特别是认可。

但是,在哺乳动物适应性免疫的情况不一样,在植物宿主中效应触发免疫编码的每一个细胞中的特异性决定有机体。

杨欧,张晓湘,徐小涵,等. 抗氧化型壳聚糖/大豆蛋白复合食用膜的制备与应用[J]. 食品工业科技,2024,45(6):210−218. doi:10.13386/j.issn1002-0306.2023050177YANG Ou, ZHANG Xiaoxiang, XU Xiaohan, et al. Preparation and Application of Antioxidative Chitosan/Soybean Protein Isolate Composite Edible Membrane[J]. Science and Technology of Food Industry, 2024, 45(6): 210−218. (in Chinese with English abstract).doi: 10.13386/j.issn1002-0306.2023050177· 包装与机械 ·抗氧化型壳聚糖/大豆蛋白复合食用膜的制备与应用杨 欧,张晓湘,徐小涵,孙 玥,梁 进,李雪玲,李梅青,张海伟*(安徽农业大学茶与食品科技学院,农业农村部江淮农产品精深加工与资源利用重点实验室,安徽省特色农产品高值化利用工程研究中心,安徽合肥 230036)摘 要:以壳聚糖和大豆分离蛋白为复合膜基材,天然抗氧化剂为活性物质,制备具有抑制脂质氧化且可食用的活性保鲜膜。

通过膜的机械性能、微观结构、物理性质与抗氧化性能,优化添加抗氧化剂的种类及浓度,并分析复合膜对核桃油贮藏保质效果。

结果表明,8种天然抗氧化剂添加均显著提高了复合膜的阻氧性能(P <0.05),其中虾青素、葡萄籽提取物、维生素C 添加后使得油脂过氧化值减少约80%,且保持良好的机械性能。

当虾青素添加浓度为0.3%时,复合膜表现最佳性能,抗拉强度为6.546 MPa ,断裂伸长率为69.962%,DPPH 自由基清除能力为80.1%,水蒸气渗透率为1.21 g∙mm/m 2∙h∙kPa ;扫描电子显微镜显示膜表面平整光滑、规则、均匀;红外光谱分析显示成膜材料间均具有良好的相容性;差示扫描热量仪分析表明虾青素复合膜的热焓值最高,达到233.940 J/g ,热稳定性最好。