第二讲:人性论研读资料

- 格式:docx

- 大小:32.14 KB

- 文档页数:7

人性论读书笔记《人性论》读书笔记在阅读《人性论》这本书的过程中,我仿佛经历了一场奇妙的思想之旅。

这可不是那种轻松随意的闲逛,而是深入到人类心灵深处的探索。

休谟在书中对于人性的探讨,让我时而深思,时而忍不住拍案叫绝。

他所提到的观念、印象、情感等概念,就像是一把把钥匙,试图打开人类内心那扇神秘的大门。

就拿其中关于印象和观念的论述来说吧。

休谟认为印象是更强烈、更生动的知觉,而观念则是印象的摹本。

这让我想起了生活中的一件小事。

有一次,我和朋友一起去爬山。

那是一个阳光明媚的日子,微风轻拂着脸颊,带来丝丝凉爽。

当我们踏上山间的小径,脚底下的石头和泥土,那种坚硬与柔软交织的触感,是如此的真实和强烈,这就是一种印象。

山上的树木郁郁葱葱,树叶在阳光的照耀下,绿得仿佛要滴出油来。

那一片片树叶的形状、纹理,还有那闪烁着的光芒,都清晰地印在我的眼中,让我感到无比的鲜活和生动。

鸟儿在枝头欢快地歌唱,那清脆的声音像是一串灵动的音符,直接钻进我的耳朵里,让我的心也跟着欢快起来。

山间小溪潺潺流淌,溪水撞击在石头上,溅起一朵朵白色的水花,那水花的形状,那水流动的姿态,还有那哗哗的声响,都是那么强烈而直接地冲击着我的感官。

当我们终于爬到山顶,俯瞰着山下的美景,那种壮阔和雄伟让我忍不住倒吸一口凉气。

远处的山峦连绵起伏,与蓝天白云相接,形成了一幅绝美的画卷。

那一刻,所有的景象、声音、气息,都深深地烙印在我的心里,成为了强烈而深刻的印象。

然而,当我回到家中,回想起这次爬山的经历时,那些原本强烈的印象就逐渐转化为了观念。

我脑海中浮现出的山的样子,不再那么清晰和生动,而是变成了一种较为模糊和抽象的概念。

鸟儿的歌声也不再那么清脆响亮,仿佛隔着一层纱。

但尽管如此,这些观念依然能够让我回忆起爬山时的美好感受,让我心生向往。

这就像休谟说的,印象是最初的、直接的体验,而观念则是在印象的基础上形成的、相对较弱的思维再现。

通过这次爬山的经历,我对他的这个观点有了更深刻的理解。

由《人性论》过渡到休谟问题及其深刻影响——休谟《人性论》读书报告摘要:休谟在《人性论》中谈及了“知性”、“情感”和“道德”,在他看来,我们对心灵以外的世界是一无所知的;宗教信仰没有根据;道德的基础是人类的感情,而不是上帝的法律。

他在《人性论》中贯彻了不可知论、怀疑论和经验主义的思想,观点令人称奇,他研究的很多规律和定理具有普适性,也正是有了这些普适性的规律和定理才有了现代文明。

《人性论》一书诞生300年来,无数的哲学家对休谟的观点试图予以反驳,几乎没有人能成功。

因此,深入研究《人性论》中的独特理论,对当今构建社会主义和谐社会及促进社会主义物质文明的精神文明的建设无疑具有重大的理论与现实意义。

关键词:休谟问题,不可知论,经验主义(经验哲学),怀疑论,资产阶级思想,和谐社会。

一作者介绍及写作背景(一)作者介绍:休谟(1711-1776),18世纪英国历史学家,经济学家,近代著名怀疑论者。

1711年5月7日生于苏格兰爱丁堡,卒于1776年8月25日。

11岁进入爱丁堡大学。

1729年起攻读哲学。

1732年刚满21岁就开始撰写他的主要哲学著作《人性论》,1734年去法国自修,继续哲学著述。

1748年出师维也纳和都灵。

1749年回家乡,潜心著述。

1751年移居爱丁堡市。

1763年任驻法使馆秘书;1765年升任使馆代办。

1767-1768年任副国务大臣。

1769年8月退休后返回爱丁堡。

1 休谟的主要著作有《人性论》、《道德和政治论说文集》、《人类理解研究》、《道德原理探究》、《宗教的自然史》、《自然宗教对话录》、《自凯撒入侵至1688年革命的英国史》(6卷)等。

(二)写作背景:休谟生活在英国资产阶级“光荣革命”结束到产业革命开始的社会变革的时代。

这时,英国资产阶级已经成为统治阶级的一部分,它继续维持同贵族的联盟以加强对劳动人民的统治,与此同时,迅速成长扩大起来的工商业资产阶级要求对这个联盟内部的关系作有益于本阶级利益的调整,并继续反对封建复辟势力。

人类群体共同的属性,简称“人性”。

什么是人性呢,就是向往对自己的有利的,远离对自己有害的。

这(种天性)是每个人所遵循的,这(种天性)是万物所生存的原因所在,这(种天性)也是所有法则(制度)制定的原则;世间万事的存在都是因为这种天性,同样世间万物的毁灭也都是因为没有适应或是失去这种天性所造成的。

在时机不成熟或对自己不利时,就委曲求全以等待时机。

所谓时机,就是最有利于完成某种事情的有利条件,它常常是事物的关键性转折,抓住它顺势而为则会产生极大的效果,一旦失去它,形势就会对自己极为不利,智者之虑,必杂于利害”,以此作为趋利避害的一条重要的法则。

人们的目标是一致的,而达到共同目标的途径却有各种各样;天下的真理是同一的,而人们思考、推究真理的思维方式和表述方式却是千差万别的。

杀一个人,无论是怎么弄死他都是次要的,重要的是他死了就行。

做成一件事,无论用什么手段,只要你做成了就行,唯一不变的就是,一个人无论做什么事,说什么样的话都是在维护他的某种利益,国与国之间的邦交,人与人之间的社交莫不如此。

一部二十五史,是人类心理留下的影像,我们取历史上的事,即知人事纷纷扰扰,皆有一定的轨道。

例如心中念及某事,即把那作为一个物体。

心中念及他,即是心中发出一根力线,与之连结。

心中喜欢他,即是想把他引之使近,如不喜欢,即是想把他推之使远,从这相推相引之中,就可把轨道寻出来。

嬴秦之末,天下苦秦苛政,陈涉振臂一呼,山东豪俊,一齐响应,陈涉并未派人去联合,何以会一齐响应呢?这是众人受秦的苛政久了,人人心中,都想把他推开,利害相同,心理相同,就成了方向相同之合力线,志同而道合。

刘邦项羽,起事之初,大家志在灭秦,目的相同,成了合力线,所以异姓之人,可以结为兄弟。

后来把秦灭了,目的物已去,现出了一座江山,刘邦想把他抢过来,项羽也想把他抢过来,力线相反,异姓兄弟就血战起来了。

再以高祖与韩彭诸人的关系言之,当项羽称霸的时候,高祖心想:只要把项羽杀死,我就好了。

第二节人性论二程能够为新儒学建构新的本体学说与形上信仰,原因一方面在于他们的天理论能够将“天”与“道”统一起来,使最高主宰与人文法则统一起来; 另一方面在于他们提出的人性论能够将超越的天理与内在的人性统一起来。

所以,在理学体系中,人性论既是一套关于人的存在与本质的学说,同时也是关于天理如何与人沟通的形上学说。

这一套学说直接涉及新儒学的形上信仰的确立问题。

自先秦至两汉、隋唐,儒家学者均对人性问题表现出强烈的兴趣和极大的关注,纷纷提出了各自对人性的理解和看法。

二程要建构新儒学、重建儒家的人文信仰,一方面要综合前代儒者对人性问题的研究成果,另一方面要根据时代要求,对人性问题作出新的解释。

他们的人性论的主要理论贡献体现在以下方面:(一)人性的分疏中国古代所讲的人性一般是指人生而具有的本质属性。

但是,对于哪些属性被称为人性,则有非常不同的看法。

二程综合了前人对人性的不同看法,将人性作了不同的分疏,以消除儒家人性思想中的分歧。

首先,二程肯定了那种“生之谓性”的看法,将人因气禀而生来就有的属性称为人性。

程颢在论述人性问题时说:“生之谓性”,性即气,气即性,生之谓也。

人生气禀,理有善恶,然不是性中元有此两物相对而生也。

有自幼而善,有自幼而恶,是气禀有然也。

善固性也,然恶亦不可不谓之性也。

盖“生之谓性”、“人生而静”以上不容说,才说性时,便已不是性也。

凡人说性,只是说“继之者善”也,孟子言人性善是也。

①程颍的“生之谓性”的观点从人的气禀等自然本性的角度来论证人性,故而肯定善、恶均是人的本性,认为片面地讲善来自性是不正确的。

这种人性学说显然是对先秦以来各家各派人性学说,包括告子、荀子等从人的自然欲求方面来思考人性问题的人性学说的综合。

程颐也是这样,他也从人的气质角度谈到性的内容。

他说:“口目耳鼻四支之欲,性也。

这种生理欲求显然均来自人的自然本性。

其次,二程亦坚持孟子的人性学说,从仁义道德方面来规定人性。

他们认为儒家基本的伦理道德均为人生而有之的本性。

人性论第二讲:观念理论休谟关于人的心灵(mind)的理论有其明显的理论兴趣,这就是为他的知识理论(或者说抽象观念的发生学)和道德理论提供理论背景和术语框架。

这就难怪这个理论没有详尽无遗地解释所有的心理现象了。

关于印象与观念的区分,以及关于观念的性质和来源的一般性讨论,是本讲的主要内容。

1. 心灵及其材料心理学有多种研究方式。

现代实验心理学通常会以行为为依据来考察心理现象,比如利用显示屏和按钮来测试知觉。

这当然不是休谟所理解的心理学。

休谟的心理学我们可以称之为内省心理学。

内省心理学的基本特色在于,把当事人自己所感知到的东西作为研究对象,因而属于第一人称观点(the first-person perspective)。

按这种观点,心理现象就是为当事人自己所感、所知、所想、所欲的东西,而不是简单地发生在他“内心里”的事情。

于是,心灵(或者说灵魂)就是这样的心理现象存在于其中的东西。

关于心灵的这种第一人称观点是休谟那个时代的一种通行看法。

这种观点与另外一种看法形成对照,这就是第三人称观点(the third-person perspective)。

后者把心理现象与他人可以观察到的行为紧密联系起来,并且把这种联系当作识别心理现象的决定性的标志。

用一个例子来说明这一点。

如果一个人按照上帝所规定的方式生活,那么按照第三人称的心灵观,我们(作为旁观者)就可以肯定地说,这个人信上帝。

但是,按第一人称的心灵观却不能肯定这一点,因为他很可能是装出来的——只有当他时常以虔诚的方式想着上帝,并且相信自己想到的那个东西是真的,我们才能说他相信上帝存在。

第一人称的心灵观把当事人所想的那个东西作为识别心理现象的决定性标志。

于是,在休谟看来,如果呈现于某人心灵的是一种感觉,那么他就感觉到了某个东西,如果这是一种热的感觉,那么他就感觉到了热。

这里,热的感觉本身就是存在于心灵的东西。

我们也许会反驳休谟说,热的是被感觉到的那个“外部的”火焰,只要接触火焰就感觉到热,因此,热必须归于火焰,而不必归于感觉。

人性论读书笔记在阅读完《人性论》这本书后,我深受启发,对人性的认识也有了更深入的思考。

书中开篇就探讨了人类认知的本质。

作者认为,人类的认知来源于感觉和经验。

我们通过感官接收到外界的信息,然后经过大脑的加工和整理,形成了对世界的认识。

这让我想到我们日常生活中对事物的判断,很多时候都是基于我们的直接感受和过往的经历。

比如,我们觉得火是热的、冰是冷的,这就是通过感觉获得的认知;而当我们再次遇到类似的情况时,会根据之前的经验做出相应的反应。

关于印象和观念的论述也十分精彩。

印象是指我们在当下直接感受到的强烈而生动的知觉,而观念则是对印象的较为模糊和微弱的复现。

比如说,我们亲眼看到一朵美丽的花,那瞬间的视觉感受就是印象;而当我们回忆起那朵花的样子时,就是观念。

这两者的关系十分密切,观念往往是印象的延伸和再现。

而且,我们的观念总是在一定程度上受到印象的限制和影响。

在谈到情感方面,作者指出情感是人性中非常重要的一部分。

情感的产生既受到外界事物的刺激,也受到我们自身内在的心理状态的影响。

比如,当我们获得成功时,会感到喜悦和自豪;而遭遇挫折时,则会感到沮丧和失落。

同时,情感还具有复杂性和多样性,同一种情感在不同的情境下可能会有不同的表现和强度。

书中对于道德的探讨也让我深思。

道德判断并非仅仅基于理性,情感在其中也发挥着重要作用。

我们对于善良和邪恶的评价,往往不仅仅是基于逻辑分析,更多的是基于我们内心的感受和直觉。

比如,看到有人帮助他人,我们会自然而然地产生赞赏和钦佩的情感,认为这是一种善的行为。

在阅读过程中,我还注意到作者对于人类理性的局限性有着清醒的认识。

人类的理性并非是无所不能的,我们在面对复杂的问题和不确定性时,常常会出现错误和偏差。

这也让我反思在日常生活中,不能过度依赖理性,而应该综合考虑情感、直觉等因素。

另外,关于自由意志和必然论的讨论也给我带来了新的思考角度。

作者认为,虽然我们在某些情况下感觉自己有自由意志,但实际上我们的行为往往是受到各种因素的必然影响。

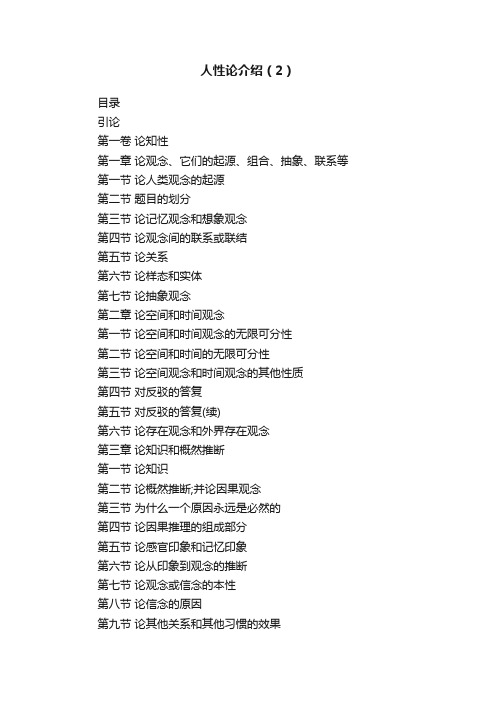

人性论介绍(2)

目录

引论

第一卷论知性

第一章论观念、它们的起源、组合、抽象、联系等第一节论人类观念的起源

第二节题目的划分

第三节论记忆观念和想象观念

第四节论观念间的联系或联结

第五节论关系

第六节论样态和实体

第七节论抽象观念

第二章论空间和时间观念

第一节论空间和时间观念的无限可分性

第二节论空间和时间的无限可分性

第三节论空间观念和时间观念的其他性质

第四节对反驳的答复

第五节对反驳的答复(续)

第六节论存在观念和外界存在观念

第三章论知识和概然推断

第一节论知识

第二节论概然推断;并论因果观念

第三节为什么一个原因永远是必然的

第四节论因果推理的组成部分

第五节论感官印象和记忆印象

第六节论从印象到观念的推断

第七节论观念或信念的本性

第八节论信念的原因

第九节论其他关系和其他习惯的效果

第十节论信念的影响

第十一节论机会的概然性

第十二节论原因的概然性

第十三节论非哲学的概然推断

第十四节论必然联系的观念

第十五节判断原因和结果所依据的规则

第十六节论动物的理性

第四章论怀疑主义哲学体系和其他哲学体系第一节论理性方面的怀疑主义

第二节论感官方面的怀疑主义

第三节论古代哲学

第四节论近代哲学

第五节论灵魂的非物质性

第六节论人格的同一性

第七节本卷的结论

……

第二卷论情感

第三卷道德学。

人性论读书笔记在阅读《人性论》这本书的过程中,我仿佛走进了一个深邃而又充满思考的世界。

作者对于人性的剖析,让我对人类自身的认识有了新的突破和启发。

书中开篇就对人类的认知能力进行了探讨。

作者认为,我们的感知可以分为印象和观念。

印象是我们在亲身经历时所产生的强烈而生动的感觉,而观念则是在印象的基础上,经过记忆和想象所形成的较为微弱和模糊的思维。

这种区分让我明白了,我们对于世界的理解和认知,往往是建立在我们所接收到的直接感受和后续的思考加工之上。

作者进一步指出,因果关系是我们理解世界的重要方式。

我们总是倾向于从一个事件的发生去推断另一个事件的必然结果。

然而,这种因果推断并非是基于绝对的必然逻辑,而是基于我们长期以来的经验积累和习惯形成。

比如,我们看到火会想到热,看到乌云会想到可能会下雨。

但这种推断并非是天生就有的,而是在我们不断地观察和体验中逐渐形成的一种思维习惯。

在谈到人性中的情感部分时,作者认为,情感的产生与我们对于事物的价值判断密切相关。

当我们认为某件事物对我们有利时,就会产生喜悦、爱等积极的情感;反之,当我们认为某件事物对我们有害时,就会产生痛苦、恨等消极的情感。

这让我思考到,我们在生活中的喜怒哀乐,其实很大程度上取决于我们对于周围事物的主观评价和认知。

同时,书中还提到了道德判断的问题。

作者认为,道德并非是先天存在的绝对标准,而是基于社会习俗和人类的共同利益而形成的。

不同的社会和文化可能会有不同的道德标准,但它们都旨在维护社会的秩序和人类的共同利益。

这使我意识到,我们对于道德的理解和判断,不能仅仅局限于个人的观点,还需要考虑到社会的整体背景和共同价值。

在阅读过程中,我也不禁思考起人性中的弱点和局限性。

例如,我们常常会受到偏见和先入为主的观念的影响,导致对事物的判断出现偏差。

我们也容易陷入自我中心的思维模式,只关注自己的利益和感受,而忽视了他人的存在和需求。

这些人性的弱点,在我们的日常生活中随处可见,也给我们带来了许多不必要的冲突和矛盾。

Part III: Knowledge and probabilitySection 7: The nature of the idea or beliefAll the perceptions of the mind are of two kinds, impressions and ideas, which differ from each other only in their different degrees of force and liveliness. Our ideas are copied from our impressions and represent them in every detail. When you want somehow to vary your idea of a particular object, all you can do is to make it more or less strong and lively. If you change it in any other way it will come to represent a different object or impression. (Similarly with colours. A particular shade of a colour may acquire a new degree of liveliness or brightness without any other variation; but if you produce any other change it is no longer the same shade or colour.) Therefore, as belief merely affects how we conceive any object, all it can do - ·the only kind of variation that won’t change the subject, so to speak· - is to make our ideas stronger and livelier. So an opinion or belief can most accurately defined as: a lively idea related to or associated with a present impression.This operation of the mind that forms the belief in any matter of fact seems to have been until now one of the greatest mysteries of philosophy, though no-one has so much as suspected that there was any difficulty in explaining it. For my part, I have to admit that I find a considerable difficulty in this, and that even when I think I understand the subject perfectly I am at a loss for words in which to express my meaning. A line of thought that seems to me to be very cogent leads me to conclude that an opinion or belief is nothing but an idea that differs from a fiction not in the nature or the order of its parts but in how it is conceived. But when I want to explain this ‘how’, I can hardly find any word that fully serves the purpose, and am obliged to appeal to your feeling in order to give you a perfect notion of this operation of the mind. An idea assented to feels different from a fictitious idea that the imagination alone presents to us; and I try to explain this difference of feeling by calling it ‘a superior force’, or ‘liveliness’, or ‘solidity’, or‘firmness’, or ‘steadiness’. This variety of terms, which may seem so unphilosophical, is intended only to express the act of the mind that makes realities more present to us than fictions, causes them to weigh more in thought, and gives them a superior influence on the passions and the imagination. Provided we agree about the thing, we need n’t argue about the labels. . . . I admit that it is impossible to explain perfectly this feeling or manner of conception thatmarks off belief. We can use words that express something near it. But its true and proper name is ‘belief’, which is a term that everyone sufficiently understands .in common life. And .in philosophy we can go no further than to say that it is something felt by the mind which distinguishes the ideas of the judgment from the fictions of the imagination. It gives them more force and influence, makes them appear of greater importance, anchors them in the mind, and makes them the governing principlesc of all our actions.Section 8iii: The causes of beliefFrom a second kind of experience I conclude that the belief that comes with the present impression, and is produced by a number of past impressions and pairs of events, arises immediately, without any new operation of the reason or imagination. I can be sure of this, because I never am conscious of any such operation in myself and don’t find anything in the situation to operate on. When something comes from a past repetition without any new reasoning or conclusion, our word for it is ‘custom’; so we can take it as certainly established every belief that follows on a present impression is derived solely from custom. When we are accustomed to see two impressions conjoined, the appearance or idea of one immediately carries us to the idea of the other.Objects have no discoverable connection with one another, and the only principle that lets us draw any inference from the appearance of one object to the existence of another is custom operating on the imagination. It is worth noting that the past experience on which all our judgments about cause and effect depend can operate on our mind so imperceptibly that we don’t notice it, and it may even be that we don’t fully know it. A person who stops short in his journey when he comes to a river in his way foresees the consequences of going forward; and his knowledge of these consequences comes from past experience which informs him of certain linkages of causes and effects. But does he reflect on any past experience, and call to mind instances that he has seen or heard of, in order to discover how water effects animal bodies? Surely not! That isn’t how he proceeds in his reasoning. ·In his mind· the idea of water is so closely connected with that of sinking, and the idea of sinking is so closely linked with that of drowning, that his mind moves from one idea to the next tothe next without help from his memory. . . . But as this transition comes from experience and not from any primary connection between the ideas, we have to acknowledge that experience can produce a belief - a judgment regarding causes and effects - by a secret operation in which it is not once thought of. This removes any pretext that may remain for asserting that the mind is convinced by reasoning of the principle that instances of which we haven’t had experience must resemble those of which we have. For we here find that the understanding or imagination can draw inferences from past experience without so much as reflecting on it - let alone forming a principle about it and reasoning on the basis of the principle!Section 9iii: The effects of other relations and other habitsBut we find by experience that belief arises only from causation, and that we can draw no inference from one object to another unless they are connected by this relation. So we can conclude that there is some error in the reasoning that has led us into such difficulties.Just as resemblance when combined with causation strengthens our reasonings, so a considerable lack of resemblance can almost entirely destroy them. A remarkable example of this is the universal carelessness and stupidity of men with regard to a future state, a topic in which they show as obstinate an in credulity as they do a blind credulity about other things. There is indeed no richer source of material for a studious man’s wonder, and a pious man’s regret, than the negligence of the bulk of mankind concerning their after-life; and it is with reason that many eminent theologians have been so bold as to say that though common people don’t explicitly assent to any form of unbelief they are really unbelievers in their hearts and have nothing like what we could call a belief that their souls are eternal. Let us consider on the one hand what divines have presented with such eloquence about the importance of eternity, which is to be spent either in heaven or in hell; and in estimating this let us reflect that though in matters of rhetoric we can expect some exaggeration, in this case we must allow that the strongest figures of speech fall infinitely short of the subject. Then let us view on the other hand how prodigiously safe men feel about this! Do these people really believe what they are taught, and what they claim to affirm? Obviously not. And I shall now explain why. If we look at this argument fromeducation in the right way, it will appear very convincing; and all the more so from being based on one of the most common phenomena that is to be met with anywhere.We are all familiar with education; and I am contending that the core of education is the production of beliefs through sheer repetition of certain ideas - that is, through creating customs of the second of the two kinds I have mentioned·. I am convinced that more than half of the opinions that prevail among mankind are products of education, and that the principles that are implicitly embraced from this cause over-balance the ones that come either from abstract reasoning or from experience. [Hume’s word‘over-balance’ might mean ‘outnumber’ or ‘overpower’ or both.] As liars through the frequent repetition of their lies come at last to remember them, so our judgment, or rather our imagination, can through similar repetition have ideas so strongly and brightly imprinted on it that they operate on the mind in the same way as do the perceptions that reach us through the senses, memory, or reason. But as education is an artificial and not a natural cause, and as its maxims are frequently contrary to reason and even to one another in different times and places, philosophers don’t take account of it ·in their theorizing about belief, though in reality it is built on almost the same foundation of custom and repetition as are our natural reasonings from causes and effects.Section 13iii: Unphilosophical probabilityWhy do men form general rules and allow them to influence their judgment, even contrary to present observation and experience? I think that it comes from the very same principles as do all judgments about causes and effects. [In the rest of this paragraph, Hume reminds us of his account of causal and probabilistic reasoning, especially stressing how the latter may be weakened by imperfect resemblances amongst the instances.] Although custom is the basis of all our judgments, sometimes it has an effect on the imagination in opposition to the judgment, and produces a contrariety in our views about the same object. Let me explain. In most kinds of causes there is a complication of factors, some essential and others superfluous, some absolutely required for the production of the effect and others present only by accident. Now, when these superfluous factors are numerous and remarkable and frequently conjoined with the essential factors, they influence the imagination so much that even in theabsence of something essential they carry us on to the idea of the usual effect, giving it a force and liveliness that make it superior to the mere fictions of the imagination. We can correct this propensity by reflecting on the nature of the factors on which it is based; but it is still certain that custom starts it off and gives a bias to the imagination.Part iv: The sceptical and other systems of philosophySection 1 Scepticism with regard to reason‘Do you sincerely assent to this argument that you seem to take such trouble to persuade us of? Are you really one of those sceptics who hold that everything is uncertain, and that our judgment doesn’t have measures of truth and falsehood on any topic?’ I reply that this question is entirely superfluous, and that neither I nor anyone else was ever sincerely and constantly of that sceptical opinion. Nature, by an absolute and uncontrollable necessity, makes us judge as well as breathe and feel; and we can’t prevent ourselves from viewing certain objects in a stronger and fuller light on account of their customary connection with a present impression, any more than we can prevent ourselves from thinking as long as we are awake, or from seeing nearby bodies when we turn our eyes towards them in broad sunlight. Whoever has taken trouble to refute the objections of this total scepticism has really been disputing without an antagonist, trying to establish by arguments a faculty that Nature has already implanted in the mind and made unavoidable.Section 2. Scepticism with regard to the sensesTo remove this difficulty, let us get help from the idea of time or duration.I have already observed in that time in a strict sense implies change, and that when we apply the idea of time to any unchanging object, supposing it to participate in the changes of the coexisting objects and in particular of the changes in our perceptions, this is only a fiction of the imagination. This fiction, which almost universally takes place, is the means by which we get a notion of identity from a single object that we survey for a period of time without observing in it any interruption or variation. Here is how it does that. We can consider any two points in this period in either of two ways: we can survey them at the very same instant, in which case they give us the idea of number: both as being two points in time, and as containing perceptions of two objects, for the objects must be multiplied in order to be conceived as existing in these two different points of time;or we can trace the succession of time by a matching succession of ideas, conceiving first one moment along with the object at that time, then imagine a change in the time without any variation or interruption in the object; and so we get the idea of unity.Here then is an idea that is intermediate between unity and number, or - more properly speaking -is either of them, according to how we look at it; and this is the idea that we call the idea of identity. We can’t in propriety of speech say that an object is the same as itself unless we mean that the object existent at one time is the same as itself existent at another. In this way we make a difference between the idea meant by ‘object’ and that meant by ‘itself’, without going as far as number yet without confining ourselves to a strict and absolute unity.This sceptical doubt, with respect to both reason and the senses, is an illness that can never be thoroughly cured; it is bound to return upon us every moment, even if we chase it away and sometimes seem to be entirely free from it. On no system is it possible to defend either our understanding (i.e. reason) or our senses, and when we try to justify them in that manner that I have been discussing we merely expose their defects further. As the sceptical doubt arises naturally from deep and hard thought about those subjects, it always increases as we think longer and harder, whether our thoughts are in opposition to sceptical doubt or conformity with it. Only carelessness and inattention can give us any remedy. For this reason I rely entirely on them; and I take it for granted that whatever you may think at this present moment, in an hour from now you will be convinced that there is both an external and internal world; and on that supposition-that there is an external as well as an internal world- I intend now to examine some general systems, ancient and modern, that have been proposed regardin g both ‘worlds’, before I proceed in section 5 to a more particular enquiry about our impressions. This may eventually be found to be relevant to the subject of the present section.Section 3. The ancient philosophySeveral moralists have recommended, as an excellent method of becoming acquainted with our own hearts and knowing our progress in virtue, to recollect our dreams in the morning and examine them asseverely as we would our most serious and deliberate actions. Our character is the same sleeping as waking, they say, and it shows up most clearly when deliberation, fear, and scheming have no place, and when men can’t try to deceive themselves or others. The generosity or baseness of our character, our mildness or cruelty, our courage or cowardice, are quite uninhibited in their influence on the fictions of the imagination, revealing themselves in the most glaring colours. In a similar way I believe that we might make some useful discoveries through a criticismof the fictions of ancient philosophy concerning substances, substantial forms, accidents, and occult qualities; those fictions, however unreasonable and capricious they may be, have a very intimate connection with the principles of human nature.4 The modern philosophyThe fundamental principle of that philosophy is the opinion about colours, sounds, tastes, smells, heat, and cold, which it asserts to be nothing but impressions in the mind, derived from the operation of external objects and without any resemblance to the qualities of the objects. Having examined the reasons commonly produced for this opinion, I find only one of them to be satisfactory, namely the one based on the variations of those impressions even while the external object seems to remain unaltered. These variations depend on various factors. Upon the different states of our health: a sick man feels a disagreeable taste in food that used to please him the most. Upon the different conditions and constitutions of men: stuff that seems bitter to one man is sweet to another. Upon differences in location and distance: colours reflected from the clouds change according to the distance of the clouds, and according to the angle they make with the eye and the luminous body. Fire also communicates the sensation of pleasure at one distance and of pain at another. Instances of this kind are very numerous and frequent.。