巴黎圣母院英文ppt

- 格式:pptx

- 大小:1.66 MB

- 文档页数:14

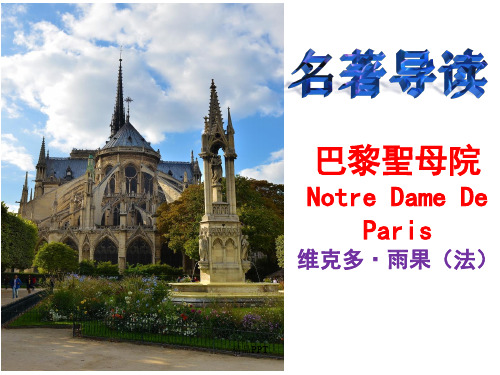

巴黎圣母院简介英⽂巴黎圣母院简介 The Cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris is a church building in the heart of Paris, France, on the island of Sidi, and the cathedral of the Catholic Diocese of Paris. Notre Dame built in the period from 1163 to 1250, is a Gothic architectural form, is the French island of Gothic church group inside, very important representative of a. Was built in 1163 years, is the Archbishop of Paris, Morris de Souley decided to build, the whole church was built in 1345, which lasted 180 years.巴黎圣母院建筑概况 【Chinese name】 Notre Dame de Paris [The seat of the church] Paris, France, Cedi (Cite) southeast [Architect] Jean de Chelles Pierre de Montreuil (Pierre de Montreuil) Jean Ravy Viollet-le-Duc (Viollet-le-Duc) 【Introduction】 Notre Dame is a Gothic style Christian church, is a symbol of ancient Paris. It stands on the banks of the Seine, in the center of the city of Paris. Its status, historical value is unparalleled, is one of the most glorious buildings in history. The church is famous for its sculptures and paintings of Gothic architectural style, altars, cloisters, doors and windows, and a large number of art treasures of the 13th to 17th centuries. Although this is a religious building, but it shines the wisdom of the French people, reflecting the people's pursuit of a better life and longing.巴黎圣母院历史沿⾰ Notre Dame of the Notre Dame "Notre Dame" intentionally "our lady", the lady does not mean someone else, it means Jesus' mother of the Virgin Mary. Notre Dame Cathedral is not the first religious building on its address, according to some of the cultural relics excavated under the church base, which is used as a religious use history, can be traced back to Rome's Tiberius (Emperor Tiberius ), In the eastern half of the island may be built with a sacrifice to Rome and Gaul God only the temple. As for the first Christian church to be built at this address, the site of Notre Dame has a twists and turns of history. In the 4th century was a Christian church used to worship St. Stephen and became a Roman church in the 6th century , And this church has 12 cornerstone from the original site of the Roman temple. It is also argued that the cathedral was reconstructed on the basis of the previously existing churches in the year 528 when Childebert I of the Mérovingiens (Mérovingiens). In the 12th century Louis VII, the original Romanesque church has been damaged, in 1160 was elected bishop of Paris, Maurice de Sully (Maurice de Sully) decided to build a place in this place and St. Tani The cathedral (the Cathedral of St. Etienne) comparable to the magnificent church. There are also historical data show that there have been two churches, one is the St. Tenny Cathedral, the other is the Virgin Mary Church. St. Tenny Cathedral as early as the 10th century, has become a Paris, or the entire French religious center. However, it is precisely because of this importance, people began to find the original St. Stephen's Church and its commitment to the task does not match, coupled with the original church has been with the time and old, and began to think about re-building the church. The Notre Dame de Paris was built in 1163 and was built in 1345. The church was once the place where the whole European artisan organization and educational organization rally. Because of these historical origins, the most famous Sorbonne in Paris is located here. At the end of the French Revolution in the late 18th century, most of the treasures of the church were destroyed or plundered, and the images of the displaced carved and the head were cut off, and the only big bell was spoiled without being destroyed. Soak a hundred holes. After the church to rational temple, and later became a wine warehouse, until 1804 Napoleon in power, it will be used for religious purposes. Victor Hugo, a famous French writer, has done his poetic design of Notre Dame in his novel "Notre Dame de Paris". This novel is written in the romantic era of French literature. After the publication of the 1831 book, it caused a great reverberation, and many people wanted to build the old-fashioned Notre Dame, and launched a fundraising program. But also caused the then authorities on the construction of the Notre Dame's concern. The restoration plan began in 1844 and was chaired by the historian and architect Eugene Viollet-le-Duc to reproduce the glory of Notre Dame. In 1845, Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Lassus, 1807-1857 and Viollet-le-Duc were responsible for the complete renovation of the church, which lasted for 23 years, Holyhall, so today we see the Notre Dame de Paris, there are many elements that are reinterpreted by them. Today, the Notre Dame is still the masterpiece of the French Gothic architecture, and almost maintained the original original style. Notre Dame also shows the history of the Gothic cathedral. Construction process In 1160, the bishop of Paris, Maurice de Sully (Maurice de Sully) initiated the church reconstruction plan, Pope Alexander III (Pope Alexander III) in 1163 personally lay the foundation (also said that the bishop of Sullivan), opened The construction of the French Gothic architecture masterpiece. 1182 years from the beginning of the construction of the singing hall, after the start of the construction of the church is very fast, so in 1182, when the Pope's angel gave a new altar, the basic function of Notre Dame is roughly formed. Until this stage, the workers began to dismantle the old church (in ancient times, the old church and the new church will not be built early to remove the church to continue the daily religious operation). In the construction plan of Notre Dame, the new building was moved eastward than the original building in order to free up a square that could serve as a parade in front of the church. In order to achieve this, the Bishop of the Pleiades will be an isolated island in the east of the island of Xidai Island and the island connected to the way to fill the building can be used to build the church. In addition, he built a lot of houses, so that we can lay a new street "Rue Neuve Notre-Dame" (Rue Neuve Notre-Dame), this six-meter-wide street is the largest medieval street in Paris The As for the bishop mansion and the church attached to the hospital (the main palace hospital), because the island is not enough land, forced to migrate to the south bank of the Seine. Then built the temple in 1208. Between 1225 and 1250, the west side of the Notre Dame was built and the minaret was built, and during the period from 1235 to 1250, many chapels were added in the main hall. Jean de Chelles and Pierre de Montreuil were responsible for the expansion of the facade of the cross of the church. In 1296 - 1330, Pierre de Chelles (Jean Ravy) completed a semicircular apse, where Xie Ye changed the door niche to see the appearance of today, and Kazakhstan Dimension completed the choir screen. The façade of the church's twin towers went to the 13th century and started in the hands of the third architect, Harvey, and in the 1220s, by the fourth architect, Duke and the roof part of the joint, together to complete. Through the French several generations of all kinds of handicrafts master: masons division, carpenters, blacksmiths, sculptors, glass carvings and so on and so on to the followers, Notre Dame finally completed in 1345, took nearly two centuries. [2] Historical events In 1239 King St. Louis placed the thorns corpses at Notre Dame. 1302 Philips - Lebel (Philippe le Bel) in Notre Dame opened the first time the Royal State convened the General Assembly. Then all kinds of rituals: grace ceremonies, weddings, coronation, baptism, funerals and so on 1430 years of the young King Henry IV coronation ceremony 1455 Violence Against Joan of Arc. National heroine Joan of Arc for the French leader of the war victory, but later sold, was executed by fire. Many years after the Church of Notre Dame to be rehabilitated, held a rehabilitated ceremony, in the courtyard erected Joan of Arc statue, from the future known as "Joan of Arc". In 1572 Margurerite of Valois married Henry of Navarre. 1687 held the funeral of the Grand Duke. In 1708 Louis XIV was in accordance with the wishes of his father to modify the altar to glorify the Virgin. December 2, 1804 Pope VII Pie VII (Pie VII) to come to the crowned Napoleon emperor. In 1811 the emperor of Rome accepted the baptism ceremony. August 26, 1944 in the Notre Dame held in Paris liberation ceremony. 1945 read the second world war victory hymns On November 12, 1970, the residence of General de Gaulle was held. May 31, 1980 Pope Paul II held an extraordinary prayer party here.。

like the Abbey of Tournus, the grave and massive frame, the large and round vault, the glacial bareness, the majestic simplicity of the edifices which have the rounded arch for their progenitor. It is not, like the Cathedral of Bourges, the magnificent, light, multiform, tufted, bristling efflorescent product of the pointed arch. Impossible to class it in that an- cient family of sombre, mysterious churches, low and crushed as it were by the round arch, almost Egyptian, with the exception of the ceiling; all hieroglyphics, all sacerdotal, all symbolical, more loaded in their orna- ments, with lozenges and zigzags, than with flowers, with flowers than with animals, with animals than with men; the work of the architect less than of the bishop; first transformation of art, all impressed with theo- cratic and military discipline, taking root in the Lower Empire, and stop- ping with the time of William the Conqueror. Impossible to place our Cathedral in that other family of lofty, aerial churches, rich in painted windows and sculpture; pointed in form, bold in attitude; communal and bourgeois as political symbols; free, capricious, lawless, as a work of art; second transformation of architecture, no longer hieroglyphic, im- movable and sacerdotal, but artistic, progressive, and popular, which be- gins at the return from the crusades, and ends with Louis IX. Notre- Dame de Paris is not of pure Romanesque, like the first; nor of pure Ara- bian race, like the second.It is an edifice of the transition period. The Saxon architect completed the erection of the first pillars of the nave, when the pointed arch, which dates from the Crusade, arrived and placed itself as a conqueror upon the large Romanesque capitals which should support only round arches. The pointed arch, mistress since that time, constructed the rest of the church. Nevertheless, timid and inexperienced at the start, it sweeps out, grows larger, restrains itself, and dares no longer dart upwards in spires and lancet windows, as it did later on, in so many marvellous cathedrals. One would say that it were conscious of the vicinity of the heavy Romanesque pillars.However, these edifices of the transition from the Romanesque to the Gothic, are no less precious for study than the pure types. They express a shade of the art which would be lost without them. It is the graft of the pointed upon the round arch.Notre-Dame de Paris is, in particular, a curious specimen of this vari- ety. Each face, each stone of the venerable monument, is a page not only of the history of the country, but of the history of science and art as well. Thus, in order to indicate here only the principal details, while the little Red Door almost attains to the limits of the Gothic delicacy of the110fifteenth century, the pillars of the nave, by their size and weight, go back to the Carlovingian Abbey of Saint-Germain des Prés. One would suppose that six centuries separated these pillars from that door. There is no one, not even the hermetics, who does not find in the symbols of the grand portal a satisfactory compendium of their science, of which the Church of Saint-Jacques de la Boucherie was so complete a hieroglyph. Thus, the Roman abbey, the philosophers’ church, the Gothic art, Saxon art, the heavy, round pillar, which recalls Gregory VII., the hermetic symbolism, with which Nicolas Flamel played the prelude to Luther, papal unity, schism, Saint-Germain des Prés, Saint-Jacques de la Boucherie,—all are mingled, combined, amalgamated in Notre-Dame. This central mother church is, among the ancient churches of Paris, a sort of chimera; it has the head of one, the limbs of another, the haunches of another, something of all.We repeat it, these hybrid constructions are not the least interesting for the artist, for the antiquarian, for the historian. They make one feel to what a degree architecture is a primitive thing, by demonstrating (what is also demonstrated by the cyclopean vestiges, the pyramids of Egypt, the gigantic Hindoo pagodas) that the greatest products of architecture are less the works of individuals than of society; rather the offspring of a nation’s effort, than the inspired flash of a man of genius; the deposit left by a whole people; the heaps accumulated by centuries; the residue of successive evaporations of human society,— in a word, species of forma- tions. Each wave of time contributes its alluvium, each race deposits its layer on the monument, each individual brings his stone. Thus do the beavers, thus do the bees, thus do men. The great symbol of architecture, Babel, is a hive.Great edifices, like great mountains, are the work of centuries. Art of- ten undergoes a transformation while they are pending, pendent opera in- terrupta; they proceed quietly in accordance with the transformed art. The new art takes the monument where it finds it, incrusts itself there, assimilates it to itself, develops it according to its fancy, and finishes it if it can. The thing is accomplished without trouble, without effort, without reaction,—following a natural and tranquil law. It is a graft which shoots up, a sap which circulates, a vegetation which starts forth anew. Certainly there is matter here for many large volumes, and often the uni- versal history of humanity in the successive engrafting of many arts at many levels, upon the same monument. The man, the artist, the indi- vidual, is effaced in these great masses, which lack the name of their111author; human intelligence is there summed up and totalized. Time is the architect, the nation is the builder.Not to consider here anything except the Christian architecture of Europe, that younger sister of the great masonries of the Orient, it ap- pears to the eyes as an immense formation divided into three well- defined zones, which are superposed, the one upon the other: the Romanesque zone20, the Gothic zone, the zone of the Renaissance, which we would gladly call the Greco-Roman zone. The Roman layer, which is the most ancient and deepest, is occupied by the round arch, which re- appears, supported by the Greek column, in the modern and upper layer of the Renaissance. The pointed arch is found between the two. The edi- fices which belong exclusively to any one of these three layers are per- fectly distinct, uniform, and complete. There is the Abbey of Jumiéges, there is the Cathedral of Reims, there is the Sainte-Croix of Orleans. But the three zones mingle and amalgamate along the edges, like the colors in the solar spectrum. Hence, complex monuments, edifices of gradation and transition. One is Roman at the base, Gothic in the middle, Greco- Roman at the top. It is because it was six hundred years in building. This variety is rare. The donjon keep of d’Etampes is a specimen of it. But monuments of two formations are more frequent. There is Notre-Dame de Paris, a pointed-arch edifice, which is imbedded by its pillars in that Roman zone, in which are plunged the portal of Saint-Denis, and the nave of Saint-Germain des Prés. There is the charming, half-Gothic chapter-house of Bocherville, where the Roman layer extends half way up. There is the cathedral of Rouen, which would be entirely Gothic if it did not bathe the tip of its central spire in the zone of the Renaissance.21 Facies non omnibus una,No diversa tamen, qualem, etc.Their faces not all alike, nor yet different, but such as the faces of sis- ters ought to be.However, all these shades, all these differences, do not affect the sur- faces of edifices only. It is art which has changed its skin. The very con- stitution of the Christian church is not attacked by it. There is always the 20.This is the same which is called, according to locality, climate, and races, Lombard, Saxon, or Byzantine. There are four sister and parallel architectures, each having its special character, but derived from the same origin, the round arch.21.This portion of the spire, which was of woodwork, is precisely that which was consumed by lightning, in 1823.112same internal woodwork, the same logical arrangement of parts. Whatever may be the carved and embroidered envelope of a cathedral, one always finds beneath it— in the state of a germ, and of a rudiment at the least— the Roman basilica. It is eternally developed upon the soil ac- cording to the same law. There are, invariably, two naves, which inter- sect in a cross, and whose upper portion, rounded into an apse, forms the choir; there are always the side aisles, for interior processions, for chapels,—a sort of lateral walks or promenades where the principal nave discharges itself through the spaces between the pillars. That settled, the number of chapels, doors, bell towers, and pinnacles are modified to infinity, according to the fancy of the century, the people, and art. The service of religion once assured and provided for, architec- ture does what she pleases. Statues, stained glass, rose windows, ar- abesques, denticulations, capitals, bas-reliefs,— she combines all these imaginings according to the arrangement which best suits her. Hence, the prodigious exterior variety of these edifices, at whose foundation dwells so much order and unity. The trunk of a tree is immovable; the fo- liage is capricious.113Chapter 2A BIRD’S-EYE VIEW OF PARISWe have just attempted to restore, for the reader’s benefit, that admirable church of Notre-Dame de Paris. We have briefly pointed out the greater part of the beauties which it possessed in the fifteenth century, and which it lacks to-day; but we have omitted the principal thing,—the view of Paris which was then to be obtained from the summits of its towers.That was, in fact,— when, after having long groped one’s way up the dark spiral which perpendicularly pierces the thick wall of the belfries, one emerged, at last abruptly, upon one of the lofty platforms inundated with light and air,— that was, in fact, a fine picture which spread out, on all sides at once, before the eye; a spectacle sui generis, of which those of our readers who have had the good fortune to see a Gothic city entire, complete, homogeneous,— a few of which still remain, Nuremberg in Bavaria and Vittoria in Spain,— can readily form an idea; or even smal- ler specimens, provided that they are well preserved,— Vitré in Brittany, Nordhausen in Prussia.The Paris of three hundred and fifty years ago—the Paris of the fif- teenth century—was already a gigantic city. We Parisians generally make a mistake as to the ground which we think that we have gained, since Paris has not increased much over one-third since the time of Louis XI. It has certainly lost more in beauty than it has gained in size.Paris had its birth, as the reader knows, in that old island of the City which has the form of a cradle. The strand of that island was its first boundary wall, the Seine its first moat. Paris remained for many centur- ies in its island state, with two bridges, one on the north, the other on the south; and two bridge heads, which were at the same time its gates and its fortresses,— the Grand-Châtelet on the right bank, the Petit-Châtelet on the left. Then, from the date of the kings of the first race, Paris, being too cribbed and confined in its island, and unable to return thither, crossed the water. Then, beyond the Grand, beyond the Petit-Châtelet, a114first circle of walls and towers began to infringe upon the country on the two sides of the Seine. Some vestiges of this ancient enclosure still re- mained in the last century; to-day, only the memory of it is left, and here and there a tradition, the Baudets or Baudoyer gate, “Porte Bagauda”. Little by little, the tide of houses, always thrust from the heart of the city outwards, overflows, devours, wears away, and effaces this wall. Philip Augustus makes a new dike for it. He imprisons Paris in a circular chain of great towers, both lofty and solid. For the period of more than a century, the houses press upon each other, accumulate, and raise their level in this basin, like water in a reservoir. They begin to deepen; they pile story upon story; they mount upon each other; they gush forth at the top, like all laterally compressed growth, and there is a rivalry as to which shall thrust its head above its neighbors, for the sake of getting a little air. The street glows narrower and deeper, every space is over- whelmed and disappears. The houses finally leap the wall of Philip Augustus, and scatter joyfully over the plain, without order, and all askew, like runaways. There they plant themselves squarely, cut them- selves gardens from the fields, and take their ease. Beginning with 1367, the city spreads to such an extent into the suburbs, that a new wall be- comes necessary, particularly on the right bank; Charles V. builds it. But a city like Paris is perpetually growing. It is only such cities that become capitals. They are funnels, into which all the geographical, political, mor- al, and intellectual water-sheds of a country, all the natural slopes of a people, pour; wells of civilization, so to speak, and also sewers, where commerce, industry, intelligence, population,— all that is sap, all that is life, all that is the soul of a nation, filters and amasses unceasingly, drop by drop, century by century.So Charles V.’s wall suffered the fate of that of Philip Augustus. At the end of the fifteenth century, the Faubourg strides across it, passes bey- ond it, and runs farther. In the sixteenth, it seems to retreat visibly, and to bury itself deeper and deeper in the old city, so thick had the new city already become outside of it. Thus, beginning with the fifteenth century, where our story finds us, Paris had already outgrown the three concent- ric circles of walls which, from the time of Julian the Apostate, existed, so to speak, in germ in the Grand-Châtelet and the Petit-Châtelet. The mighty city had cracked, in succession, its four enclosures of walls, like a child grown too large for his garments of last year. Under Louis XI., this sea of houses was seen to be pierced at intervals by several groups of ruined towers, from the ancient wall, like the summits of hills in an in- undation,—like archipelagos of the old Paris submerged beneath the115new. Since that time Paris has undergone yet another transformation, unfortunately for our eyes; but it has passed only one more wall, that of Louis XV., that miserable wall of mud and spittle, worthy of the king who built it, worthy of the poet who sung it,—Le mur murant Paris rend Paris murmurant.22In the fifteenth century, Paris was still divided into three wholly dis- tinct and separate towns, each having its own physiognomy, its own spe- cialty, its manners, customs, privileges, and history: the City, the University, the Town. The City, which occupied the island, was the most ancient, the smallest, and the mother of the other two, crowded in between them like (may we be pardoned the comparison) a little old wo- man between two large and handsome maidens. The University covered the left bank of the Seine, from the Tournelle to the Tour de Nesle, points which correspond in the Paris of to-day, the one to the wine market, the other to the mint. Its wall included a large part of that plain where Julian had built his hot baths. The hill of Sainte-Geneviève was enclosed in it.The culminating point of this sweep of walls was the Papal gate, that is to say, near the present site of the Pantheon. The Town, which was the largest of the three fragments of Paris, held the right bank. Its quay, broken or interrupted in many places, ran along the Seine, from the Tour de Billy to the Tour du Bois; that is to say, from the place where the granary stands to-day, to the present site of the Tuileries. These four points, where the Seine intersected the wall of the capital, the Tournelle and the Tour de Nesle on the right, the Tour de Billy and the Tour du Bois on the left, were called pre-eminently, “the four towers of Paris.”The Town encroached still more extensively upon the fields than the University. The culminating point of the Town wall (that of Charles V.) was at the gates of Saint-Denis and Saint-Martin, whose situation has not been changed.As we have just said, each of these three great divisions of Paris was a town, but too special a town to be complete, a city which could not get along without the other two. Hence three entirely distinct aspects: churches abounded in the City; palaces, in the Town; and colleges, in the University. Neglecting here the originalities, of secondary importance in old Paris, and the capricious regulations regarding the public highways, we will say, from a general point of view, taking only masses and the22.The wall walling Paris makes Paris murmur.116whole group, in this chaos of communal jurisdictions, that the island be- longed to the bishop, the right bank to the provost of the merchants, the left bank to the Rector; over all ruled the provost of Paris, a royal not a municipal official. The City had Notre-Dame; the Town, the Louvre and the Hôtel de Ville; the University, the Sorbonne. The Town had the mar- kets (Halles); the city, the Hospital; the University, the Pré-aux-Clercs. Offences committed by the scholars on the left bank were tried in the law courts on the island, and were punished on the right bank at Mont- fauçon; unless the rector, feeling the university to be strong and the king weak, intervened; for it was the students’ privilege to be hanged on their own grounds.The greater part of these privileges, it may be noted in passing, and there were some even better than the above, had been extorted from the kings by revolts and mutinies. It is the course of things from time imme- morial; the king only lets go when the people tear away. There is an old charter which puts the matter naively: apropos of fidelity: Civibus fidelitas in reges, quoe tamen aliquoties seditionibus interrypta, multa peperit privileyia. In the fifteenth century, the Seine bathed five islands within the walls of Paris: Louviers island, where there were then trees, and where there is no longer anything but wood; l’ile aux Vaches, and l’ile Notre-Dame, both deserted, with the exception of one house, both fiefs of the bishop—in the seventeenth century, a single island was formed out of these two, which was built upon and named l’ile Saint-Louis— , lastly the City, and at its point, the little islet of the cow tender, which was afterwards en- gulfed beneath the platform of the Pont-Neuf. The City then had five bridges: three on the right, the Pont Notre-Dame, and the Pont au Change, of stone, the Pont aux Meuniers, of wood; two on the left, the Petit Pont, of stone, the Pont Saint-Michel, of wood; all loaded with houses.The University had six gates, built by Philip Augustus; there were, be- ginning with la Tournelle, the Porte Saint-Victor, the Porte Bordelle, the Porte Papale, the Porte Saint-Jacques, the Porte Saint-Michel, the Porte Saint-Germain. The Town had six gates, built by Charles V.; beginning with the Tour de Billy they were: the Porte Saint-Antoine, the Porte du Temple, the Porte Saint-Martin, the Porte Saint-Denis, the Porte Mont- martre, the Porte Saint-Honoré. All these gates were strong, and also handsome, which does not detract from strength. A large, deep moat, with a brisk current during the high water of winter, bathed the base of the wall round Paris; the Seine furnished the water. At night, the gates117were shut, the river was barred at both ends of the city with huge iron chains, and Paris slept tranquilly.From a bird’s-eye view, these three burgs, the City, the Town, and the University, each presented to the eye an inextricable skein of eccentric- ally tangled streets. Nevertheless, at first sight, one recognized the fact that these three fragments formed but one body. One immediately per- ceived three long parallel streets, unbroken, undisturbed, traversing, al- most in a straight line, all three cities, from one end to the other; from North to South, perpendicularly, to the Seine, which bound them togeth- er, mingled them, infused them in each other, poured and transfused the people incessantly, from one to the other, and made one out of the three. The first of these streets ran from the Porte Saint-Martin: it was called the Rue Saint-Jacques in the University, Rue de la Juiverie in the City, Rue Saint-Martin in the Town; it crossed the water twice, under the name of the Petit Pont and the Pont Notre-Dame. The second, which was called the Rue de la Harpe on the left bank, Rue de la Barillerié in the island, Rue Saint-Denis on the right bank, Pont Saint-Michel on one arm of the Seine, Pont au Change on the other, ran from the Porte Saint-Michel in the University, to the Porte Saint-Denis in the Town. However, under all these names, there were but two streets, parent streets, generating streets,—the two arteries of Paris. All the other veins of the triple city either derived their supply from them or emptied into them. Independently of these two principal streets, piercing Paris diametric- ally in its whole breadth, from side to side, common to the entire capital, the City and the University had also each its own great special street, which ran lengthwise by them, parallel to the Seine, cutting, as it passed, at right angles, the two arterial thoroughfares. Thus, in the Town, one descended in a straight line from the Porte Saint-Antoine to the Porte Saint-Honoré; in the University from the Porte Saint-Victor to the Porte Saint-Germain. These two great thoroughfares intersected by the two first, formed the canvas upon which reposed, knotted and crowded to- gether on every hand, the labyrinthine network of the streets of Paris. In the incomprehensible plan of these streets, one distinguished likewise, on looking attentively, two clusters of great streets, like magnified sheaves of grain, one in the University, the other in the Town, which spread out gradually from the bridges to the gates.Some traces of this geometrical plan still exist to-day.118Now, what aspect did this whole present, when, as viewed from the summit of the towers of Notre-Dame, in 1482? That we shall try to describe.For the spectator who arrived, panting, upon that pinnacle, it was first a dazzling confusing view of roofs, chimneys, streets, bridges, places, spires, bell towers. Everything struck your eye at once: the carved gable, the pointed roof, the turrets suspended at the angles of the walls; the stone pyramids of the eleventh century, the slate obelisks of the fifteenth; the round, bare tower of the donjon keep; the square and fretted tower of the church; the great and the little, the massive and the aerial. The eye was, for a long time, wholly lost in this labyrinth, where there was noth- ing which did not possess its originality, its reason, its genius, its beauty,—nothing which did not proceed from art; beginning with the smallest house, with its painted and carved front, with external beams, elliptical door, with projecting stories, to the royal Louvre, which then had a colonnade of towers. But these are the principal masses which were then to be distinguished when the eye began to accustom itself to this tumult of edifices.In the first place, the City.—“The island of the City,” as Sauval says, who, in spite of his confused medley, sometimes has such happy turns of expression,—“the island of the city is made like a great ship, stuck in the mud and run aground in the current, near the centre of the Seine.”We have just explained that, in the fifteenth century, this ship was anchored to the two banks of the river by five bridges. This form of a ship had also struck the heraldic scribes; for it is from that, and not from the siege by the Normans, that the ship which blazons the old shield of Paris, comes, according to Favyn and Pasquier. For him who under- stands how to decipher them, armorial bearings are algebra, armorial bearings have a tongue. The whole history of the second half of the Middle Ages is written in armorial bearings,—the first half is in the symbolism of the Roman churches. They are the hieroglyphics of feudal- ism, succeeding those of theocracy.Thus the City first presented itself to the eye, with its stern to the east, and its prow to the west. Turning towards the prow, one had before one an innumerable flock of ancient roofs, over which arched broadly the lead-covered apse of the Sainte-Chapelle, like an elephant’s haunches loaded with its tower. Only here, this tower was the most audacious, the most open, the most ornamented spire of cabinet-maker’s work that ever let the sky peep through its cone of lace. In front of Notre-Dame, and119very near at hand, three streets opened into the cathedral square,— a fine square, lined with ancient houses. Over the south side of this place bent the wrinkled and sullen façade of the Hôtel Dieu, and its roof, which seemed covered with warts and pustules. Then, on the right and the left, to east and west, within that wall of the City, which was yet so contrac- ted, rose the bell towers of its one and twenty churches, of every date, of every form, of every size, from the low and wormeaten belfry of Saint- Denis du Pas (Carcer Glaueini) to the slender needles of Saint-Pierre aux Boeufs and Saint-Landry.Behind Notre-Dame, the cloister and its Gothic galleries spread out to- wards the north; on the south, the half-Roman palace of the bishop; on the east, the desert point of the Terrain. In this throng of houses the eye also distinguished, by the lofty open-work mitres of stone which then crowned the roof itself, even the most elevated windows of the palace, the Hôtel given by the city, under Charles VI., to Juvénal des Ursins; a little farther on, the pitch-covered sheds of the Palus Market; in still an- other quarter the new apse of Saint-Germain léVieux, lengthened in 1458, with a bit of the Rue aux Febves; and then, in places, a square crowded with people; a pillory, erected at the corner of a street; a fine fragment of the pavement of Philip Augustus, a magnificent flagging, grooved for the horses’ feet, in the middle of the road, and so badly re- placed in the sixteenth century by the miserable cobblestones, called the “pavement of the League;” a deserted back courtyard, with one of those diaphanous staircase turrets, such as were erected in the fifteenth cen- tury, one of which is still to be seen in the Rue des Bourdonnais. Lastly, at the right of the Sainte-Chapelle, towards the west, the Palais de Justice rested its group of towers at the edge of the water. The thickets of the king’s gardens, which covered the western point of the City, masked the Island du Passeur. As for the water, from the summit of the towers of Notre-Dame one hardly saw it, on either side of the City; the Seine was hidden by bridges, the bridges by houses.And when the glance passed these bridges, whose roofs were visibly green, rendered mouldy before their time by the vapors from the water, if it was directed to the left, towards the University, the first edifice which struck it was a large, low sheaf of towers, the Petit-Chàtelet, whose yawning gate devoured the end of the Petit-Pont. Then, if your view ran along the bank, from east to west, from the Tournelle to the Tour de Nesle, there was a long cordon of houses, with carved beams, stained-glass windows, each story projecting over that beneath it, an in- terminable zigzag of bourgeois gables, frequently interrupted by the120mouth of a street, and from time to time also by the front or angle of a huge stone mansion, planted at its ease, with courts and gardens, wings and detached buildings, amid this populace of crowded and narrow houses, like a grand gentleman among a throng of rustics. There were five or six of these mansions on the quay, from the house of Lorraine, which shared with the Bernardins the grand enclosure adjoining the Tournelle, to the Hôtel de Nesle, whose principal tower ended Paris, and whose pointed roofs were in a position, during three months of the year, to encroach, with their black triangles, upon the scarlet disk of the setting sun.This side of the Seine was, however, the least mercantile of the two. Students furnished more of a crowd and more noise there than artisans, and there was not, properly speaking, any quay, except from the Pont Saint-Michel to the Tour de Nesle. The rest of the bank of the Seine was now a naked strand, the same as beyond the Bernardins; again, a throng of houses, standing with their feet in the water, as between the two bridges.There was a great uproar of laundresses; they screamed, and talked, and sang from morning till night along the beach, and beat a great deal of linen there, just as in our day. This is not the least of the gayeties of Paris.The University presented a dense mass to the eye. From one end to the other, it was homogeneous and compact. The thousand roofs, dense, an- gular, clinging to each other, composed, nearly all, of the same geomet- rical element, offered, when viewed from above, the aspect of a crystal- lization of the same substance.The capricious ravine of streets did not cut this block of houses into too disproportionate slices. The forty-two colleges were scattered about in a fairly equal manner, and there were some everywhere. The amus- ingly varied crests of these beautiful edifices were the product of the same art as the simple roofs which they overshot, and were, actually, only a multiplication of the square or the cube of the same geometrical figure. Hence they complicated the whole effect, without disturbing it; completed, without overloading it. Geometry is harmony. Some fine mansions here and there made magnificent outlines against the pictur- esque attics of the left bank. The house of Nevers, the house of Rome, the house of Reims, which have disappeared; the Hôtel de Cluny, which still exists, for the consolation of the artist, and whose tower was so stupidly deprived of its crown a few years ago. Close to Cluny, that Roman121。

LIVRE PREMIERILA GRAND'SALLEIl y a aujourd'hui trois cent quarante-huit ans six mois et dix-neuf jours que les parisiens s'éveillèrent au bruit de toutes les cloches sonnant à grande volée dans la triple enceinte de la Cité, de l'Université et de la Ville.Ce n'est cependant pas un jour dont l'histoire ait gardé souvenir que le 6 janvier 1482. Rien de notable dans l'événement qui mettait ainsi en branle, dès le matin, les cloches et les bourgeois de Paris. Ce n'était ni un assaut de picards ou de bourguignons, ni une châsse menée en procession, ni une révolte d'écoliers dans la vigne de Laas, ni une entrée de notredit très redouté seigneur monsieur le roi, ni même une belle pendaison delarrons et de larronnesses à la Justice de Paris. Ce n'était pas non plus la survenue, si fréquente au quinzième siècle, de quelque ambassade chamarrée et empanachée. Il y avait à peine deux jours que la dernière cavalcade de ce genre, celle des ambassadeurs flamands chargés de conclure le mariage entre le dauphin et Marguerite de Flandre, avait fait son entrée à Paris, au grand ennui de Monsieur le cardinal de Bourbon, qui, pour plaire au roi, avait dû faire bonne mine à toute cette rustique cohue de bourgmestres flamands, et les régaler, en son hôt el de Bourbon, d'une moult belle moralité, sotie et farce, tandis qu'une pluie battante inondait à sa porte ses magnifiques tapisseries.Le 6 janvier, ce qui mettait en émotion tout le populaire de Paris, comme dit Jehan de Troyes, c'était la double solenn ité, réunie depuis un temps immémorial, du jour des Rois et de la Fête des Fous.Ce jour-là, il devait y avoir feu de joie à la Grève, plantation de mai à la chapelle de Braque et mystère au Palais de Justice. Le cri en avait été fait la veille à son detrompe dans les carrefours, par les gens de Monsieur le prévôt, en beaux hoquetons de camelot violet, avec de grandes croix blanches sur la poitrine.La foule des bourgeois et des bourgeoises s'acheminait donc de toutes parts dès le matin, maisons et boutiqu es fermées, vers l'un des trois endroits désignés. Chacun avait pris parti, qui pour le feu de joie, qui pour le mai, qui pour le mystère. Il faut dire, à l'éloge de l'antique bon sens des badauds de Paris, que la plus grande partie de cette foule se dirig eait vers le feu de joie, lequel était tout à fait de saison, ou vers le mystère, qui devait être représenté dans la grand'salle du Palais bien couverte et bien close, et que les curieux s'accordaient à laisser le pauvre mai mal fleuri grelotter tout seul sous le ciel de janvier dans le cimetière de la chapelle de Braque.Le peuple affluait surtout dans les avenues du Palais de Justice, parce qu'on savait que les ambassadeurs flamands, arrivés de la surveille, se proposaient d'assister à la représentation du mystère et à l'électiondu pape des fous, laquelle devait se faire également dans la grand'salle.Ce n'était pas chose aisée de pénétrer ce jour-là dans cette grand'salle, réputée cependant alors la plus grande enceinte couverte qui fût au monde. (Il est vrai que Sauval n'avait pas encore mesuré la grande salle du château de Montargis.) La place du Palais, encombrée de peuple, offrait aux curieux des fenêtres l'aspect d'une mer, dans laquelle cinq ou six rues, comme autant d'embouchures de fleuves, dégorgeaient à chaque instant de nouveaux flots de têtes. Les ondes de cette foule, sans cesse grossies, se heurtaient aux angles des maisons qui s'avançaient çà et là, comme autant de promontoires, dans le bassin irrégulier de la place. Au centre de la haute façade gothique du Palais, le grand escalier, sans relâche remonté et descendu par un double courant qui, après s'être brisé sous le perron intermédiaire, s'épandait à larges vagues sur ses deux pentes latérales, le grand escalier, dis-je, ruisselait incessamment dans la place comme une cascade dansun lac. Les cris, les rires, le trépignement de ces mille pieds faisaient un grand bruit et une grande clameur. De temps en temps cette clameur et ce bruit redoublaient, le courant qui poussait toute cette foule vers le grand escalier rebroussait, se troublait, tourbillonnait. C'était une bourrade d'un archer ou le cheval d'un sergent de la prévôté qui ruait pour rétablir l'ordre ; admirable tradition que la prévôté a léguée à la connétablie, la connétablie à la maréchaussée, et la maréchaussée à notre gendarmerie de Paris.Aux portes, aux fenêtres, aux lucarnes, sur les toits, fourmillaient des milliers de bonnes figures bourgeoises, calmes et honnêtes, regardant le palais, regardant la cohue, et n'en demandant pas davantage ; car bien des gens à Paris se contentent du spectacle des spectateurs, et c'est déjà pour nous une chose très curieuse qu'une muraille derrière laquelle il se passe quelque chose.S'il pouvait nous être donné à nous, hommes de 1830, de nous mêler en pensée à ces parisiens du quinzième siècle et d'entrer avec eux, tiraillés, coudoyés, culbutés,dans cette immense salle du Palais, si étroite le 6 janvier 1482, le spectacle ne serait ni sans intérêt ni sans charme, et nous n'aurions autour de nous que des choses si vieilles qu'elles nous sembleraient toutes neuves.Si le lecteur y consent, nous essaierons de retrouver par la pensée l'impression qu'il eût éprouvée avec nous en franchissant le seuil de cette grand'salle au milieu de cette cohue en surcot, en hoqueton et en cotte-hardie.Et d'abord, bourdonnement dans les oreilles, éblouissement dans les yeux. Au-dessus de nos têtes une double voûte en ogive, lambrissée en sculptures de bois, peinte d'azur, fleurdelysée en or ; sous nos pieds, un pavé alternatif de marbre blanc et noir. À quelques pas de nous, un énorme pilier, puis un autre, puis un autre ; en tout sept piliers dans la longueur de la salle, soutenant au milieu de sa largeur les retombées de la double voûte. Autour des quatre premiers pi liers, des boutiques de marchands, tout étincelantes de verre et de clinquants ; autour des trois derniers, des bancs debois de chêne, usés et polis par le haut-de-chausses des plaideurs et la robe des procureurs. À l'entour de la salle, le long de la haute muraille, entre les portes, entre les croisées, entre les piliers, l'interminable rangée des statues de tous les rois de France depuis Pharamond ; les rois fainéants, les bras pendants et les yeux baissés ; les rois vaillants et bataillards, la tête et les mains hardiment levées au ciel. Puis, aux longues fenêtres ogives, des vitraux de mille couleurs ; aux larges issues de la salle, de riches portes finement sculptées ; et le tout, voûtes, piliers, murailles, chambranles, lambris, portes, statues, recouvert du haut en bas d'une splendide enluminure bleu et or, qui, déjà un peu ternie à l'époque où nous la voyons, avait presque entièrement disparu sous la poussière et les toiles d'araignée en l'an de grâce 1549, où Du Breul l'admirait encore par tradition.Qu'on se représente maintenant cette immense salle oblongue, éclairée de la clarté blafarde d'un jour de janvier, envahie par une foule bariolée et bruyante quidérive le long des murs et tournoie autour des sept piliers, et l'on aura déjà une idée confu se de l'ensemble du tableau dont nous allons essayer d'indiquer plus précisément les curieux détails.Il est certain que, si Ravaillac n'avait point assassiné Henri IV, il n'y aurait point eu de pièces du procès de Ravaillac déposées au greffe du Palais de Justice ; point de complices intéressés à faire disparaître lesdites pièces ; partant, point d'incendiaires obligés, faute de meilleur moyen, à brûler le greffe pour brûler les pièces, et à brûler le Palais de Justice pour brûler le greffe ; par conséquen t enfin, point d'incendie de 1618. Le vieux Palais serait encore debout avec sa vieille grand'salle ; je pourrais dire au lecteur : Allez la voir ; et nous serions ainsi dispensés tous deux, moi d'en faire, lui d'en lire une description telle quelle. - Ce qui prouve cette vérité neuve : que les grands événements ont des suites incalculables.Il est vrai qu'il serait fort possible d'abord que Ravaillac n'eût pas de complices, ensuite que ses complices, si parhasard il en avait, ne fussent pour rien dans l'incendie de 1618. Il en existe deux autres explications très plausibles. Premièrement, la grande étoile enflammée, large d'un pied, haute d'une coudée, qui tomba, comme chacun sait, du ciel sur le Palais, le 7 mars après minuit. Deuxièmement, le quatrain de Théophile :Certes, ce fut un triste jeuQuand à Paris dame Justice,Pour avoir mangé trop d'épice,Se mit tout le palais en feu.Quoi qu'on pense de cette triple explication politique, physique, poétique, de l'incendie du Palais de Justice en 1618, le fait malheureusement certain, c'est l'incendie. Il reste bien peu de chose aujourd'hui, grâce à cette catastrophe, grâce surtout aux diverses restaurations successives qui ont achevé ce qu'elle avait épargné, il reste bien peu de chose de cette première demeure des rois de France, de ce palais aîné du Louvre, déjà si vieux du temps de Philippe le Bel qu'on y cherchait les traces des magnifiques bâtiments élevés par le roi Robert et décrits par Helgaldus. Presque tout a disparu.Qu'est devenue la chambre de la ch ancellerie où saint Louis consomma son mariage? le jardin où il rendait la justice, " vêtu d'une cotte de camelot, d'un surcot de tiretaine sans manches, et d'un manteau par-dessus de sandal noir, couché sur des tapis, avec Joinville " ? Où est la chambre de l'empereur Sigismond ? celle de Charles IV ? celle de Jean sans Terre ? Où est l'escalier d'où Charles VI promulgua son édit de grâce ? la dalle où Marcel égorgea, en présence du dauphin, Robert de Clermont et le maréchal de Champagne ? le guichet où f urent lacérées les bulles de l'antipape Bénédict, et d'où repartirent ceux qui les avaient apportées, chapés et mitrés en dérision, et faisant amende honorable par tout Paris ? et la grand'salle, avec sa dorure, son azur, ses ogives, ses statues, ses pilie rs, son immense voûte toute déchiquetée de sculptures ? et la chambre dorée ? et le lion de pierre qui se tenait à la porte, la tête baissée, la queue entre les jambes, comme les lions du trône de Salomon, dans l'attitude humiliée qui convient à la force devant la justice ? et les belles portes ? et lesbeaux vitraux ? et les ferrures ciselées qui décourageaient Biscornette ? et les délicates menuiseries de Du Hancy ?... Qu'a fait le temps, qu'ont fait les hommes de ces merveilles ? Que nous a-t-on donné pour tout cela, pour toute cette histoire gauloise, pour tout cet art gothique ? les lourds cintres surbaissés de M. de Brosse, ce gauche architecte du portail Saint-Gervais, voilà pour l'art ; et quant à l'histoire, nous avons les souvenirs bavards du gros pilier, encore tout retentissant des commérages des Patrus.Ce n'est pas grand'chose. - Revenons à la véritable grand'salle du véritable vieux Palais.Les deux extrémités de ce gigantesque parallélogramme étaient occupées, l'une par la fameuse table de mar bre, si longue, si large et si épaisse que jamais on ne vit, disent les vieux papiers terriers, dans un style qui eût donné appétit à Gargantua, pareille tranche de marbre au monde; l'autre, par la chapelle où Louis XI s'était fait sculpter à genoux devant la Vierge, et où il avait fait transporter, sans se soucier de laisser deux niches videsdans la file des statues royales, les statues de Charlemagne et de saint Louis, deux saints qu'il supposait fort en crédit au ciel comme rois de France. Cette chapel le, neuve encore, bâtie à peine depuis six ans, était toute dans ce goût charmant d'architecture délicate, de sculpture merveilleuse, de fine et profonde ciselure qui marque chez nous la fin de l'ère gothique et se perpétue jusque vers le milieu du seizième siècle dans les fantaisies féeriques de la renaissance. La petite rosace à jour percée au-dessus du portail était en particulier un chef-d'oeuvre de ténuité et de grâce ; on eût dit une étoile de dentelle.Au milieu de la salle, vis-à-vis la grande porte, une estrade de brocart d'or, adossée au mur, et dans laquelle était pratiquée une entrée particulière au moyen d'une fenêtre du couloir de la chambre dorée, avait été élevée pour les envoyés flamands et les autres gros personnages conviés à la représentation du mystère.C'est sur la table de marbre que devait, selon l'usage, être représenté le mystère. Elle avait été disposée pourcela dès le matin ; sa riche planche de marbre, toute rayée par les talons de la basoche, supportait une cage de charpente ass ez élevée, dont la surface supérieure, accessible aux regards de toute la salle, devait servir de théâtre, et dont l'intérieur, masqué par des tapisseries, devait tenir lieu de vestiaire aux personnages de la pièce. Une échelle, naïvement placée en dehors,devait établir la communication entre la scène et le vestiaire, et prêter ses roides échelons aux entrées comme aux sorties. Il n'y avait pas de personnage si imprévu, pas de péripétie, pas de coup de théâtre qui ne fût tenu de monter par cette échelle. Innocente et vénérable enfance de l'art et des machines !Quatre sergents du bailli du Palais, gardiens obligés de tous les plaisirs du peuple les jours de fête comme les jours d'exécution, se tenaient debout aux quatre coins de la table de marbre.Ce n'était qu'au douzième coup de midi sonnant à la grande horloge du Palais que la pièce devait commencer. C'était bien tard sans doute pour unereprésentation théâtrale ; mais il avait fallu prendre l'heure des ambassadeurs.Or toute cette multitude attendait depuis le matin. Bon nombre de ces honnêtes curieux grelottaient dès le point du jour devant le grand degré du Palais ; quelques-uns même affirmaient avoir passé la nuit en travers de la grande porte pour être sûrs d'entrer les premiers. La foule s'épaississait à tout moment, et, comme une eau qui dépasse son niveau, commençait à monter le long des murs, à s'enfler autour des piliers, à déborder sur les entablements, sur les corniches, sur les appuis des fenêtres, sur toutes les saillies de l'architecture, sur tous les reliefs de la sculpture. Aussi la gêne, l'impatience, l'ennui, la liberté d'un jour de cynisme et de folie, les querelles qui éclataient à tout propos pour un coude pointu ou un soulier ferré, la fatigue d'une longue attente, donnaient-elles déjà, bien avant l'heure où les ambassadeurs devaient arriver, un accent aigre et amer à la clameur de ce peuple enfermé, emboîté, pressé, foulé, étouffé. On n'entendait queplaintes et imprécations contre les flamands, le prévôt des marchands, le cardinal de Bourbon, le bailli du Palais, madame Marguerite d'Autriche, les sergents à verge, le froid, le chaud, le mauvais temps, l'évêque de Paris, le pape des fous, les piliers, les statues, cette porte fermée, cette fenêtre ouverte ; le tout au grand amusement d es bandes d'écoliers et de laquais disséminées dans la masse, qui mêlaient à tout ce mécontentement leurs taquineries et leurs malices, et piquaient, pour ainsi dire, à coups d'épingle la mauvaise humeur générale.Il y avait entre autres un groupe de ces j oyeux démons qui, après avoir défoncé le vitrage d'une fenêtre, s'était hardiment assis sur l'entablement, et de là plongeait tour à tour ses regards et ses railleries au dedans et au dehors, dans la foule de la salle et dans la foule de la place. À leurs gestes de parodie, à leurs rires éclatants, aux appels goguenards qu'ils échangeaient d'un bout à l'autre de la salle avec leurs camarades, il était aisé de juger que ces jeunes clercs ne partageaient pas l'ennui etla fatigue du reste des assistants, et qu'ils savaient fort bien, pour leur plaisir particulier, extraire de ce qu'ils avaient sous les yeux un spectacle qui leur faisait attendre patiemment l'autre.- Sur mon âme, c'est vous, Joannes Frollo de Molendino !criait l'un d'eux à une espèce de petit diable blond, à jolie et maligne figure, accroché aux acanthes d'un chapiteau ; vous êtes bien nommé Jehan du Moulin, car vos deux bras et vos deux jambes ont l'air de quatre ailes qui vont au vent. - Depuis combien de temps êtes-vous ici ?- Par la miséricorde du diable, répondit Joannes Frollo, voilà plus de quatre heures, et j'espère bien qu'elles me seront comptées sur mon temps de purgatoire. J'ai entendu les huit chantres du roi de Sicile entonner le premier verset de la haute messe de sept heures dans la Sainte-Chapelle.- De beaux chantres, reprit l'autre, et qui ont la voix encore plus pointue que leur bonnet ! Avant de fonderune messe à monsieur saint Jean, le roi aurait bien dû s'informer si monsieur saint Jean aime le latin psalmodié avec accent provençal.- C'est pour employer ces maudits chantres du roi de Sicile qu'il a fait cela ! cria aigrement une vieille femme dans la foule au bas de la fenêtre. Je vous demande un peu ! mille livres parisis pour une messe ! et sur la ferme du poisson de mer des halles de Paris, encore !- Paix ! vieille, reprit un gros et grave personnage qui se bouchait le nez à côté de la marchande de poisson ; il fallait bien fonder une messe. Vouliez-vous pas que le roi retombât malade ?- Bravement parlé, sire Gilles Lecornu, maître pelletier-fourreur des robes du roi ! cria le petit écolier cramponné au chapiteau.Un éclat de rire de tous les écoliers accueillit le nom malencontreux du pauvre pelletier-fourreur des robes du roi.- Lecornu ! Gilles Lecornu ! disaient les uns.- Cornutus et hirsutus, reprenait un autre.- Hé ! sans doute, continuait le petit démon du chapiteau. Qu'ont-ils à rire ? Honorable homme Gilles Lecornu, frère de maître Jehan Lecornu, prévôt de l'hôtel du roi, fils de maître Mahiet Lecornu, premi er portier du bois de Vincennes, tous bourgeois de Paris, tous mariés de père en fils !La gaieté redoubla. Le gros pelletier-fourreur, sans répondre un mot, s'efforçait de se dérober aux regards fixés sur lui de tous côtés ; mais il suait et soufflait en vain : comme un coin qui s'enfonce dans le bois, les efforts qu'il faisait ne servaient qu'à emboîter plus solidement dans les épaules de ses voisins sa large face apoplectique, pourpre de dépit et de colère.Enfin un de ceux-ci, gros, court et vénérable c omme lui, vint à son secours.- Abomination ! des écoliers qui parlent de la sorte à un bourgeois ! de mon temps on les eût fustigés avec un fagot dont on les eût brûlés ensuite.La bande entière éclata.- Holàhée ! qui chante cette gamme ? quel est le cha t-huant de malheur ?- Tiens, je le reconnais, dit l'un ; c'est maître Andry Musnier.- Parce qu'il est un des quatre libraires jurés de l'Université ! dit l'autre.- Tout est par quatre dans cette boutique, cria un troisième : les quatre nations, les quatre facultés, les quatre fêtes, les quatre procureurs, les quatre électeurs, les quatre libraires.- Eh bien, reprit Jean Frollo, il faut leur faire le diable à quatre.- Musnier, nous brûlerons tes livres.- Musnier, nous battrons ton laquais.- Musnier, nous chiffonnerons ta femme.- La bonne grosse mademoiselle Oudarde.- Qui est aussi fraîche et aussi gaie que si elle était veuve.- Que le diable vous emporte ! grommela maître Andry Musnier.- Maître Andry, reprit Jehan, toujours pendu à son chapiteau, tais-toi, ou je te tombe sur la tête !Maître Andry leva les yeux, parut mesurer un instant la hauteur du pilier, la pesanteur du drôle, multiplia mentalement cette pesanteur par le carré de la vitesse, et se tut.Jehan, maître du champ de bataille, poursui vit avec triomphe :- C'est que je le ferais, quoique je sois frère d'un archidiacre !- Beaux sires, que nos gens de l'Université ! n'avoir seulement pas fait respecter nos privilèges dans un jour comme celui-ci ! Enfin, il y a mai et feu de joie à la Vil le ; mystère, pape des fous et ambassadeurs flamands à la Cité ; et à l'Université, rien !- Cependant la place Maubert est assez grande ! reprit un des clercs cantonnés sur la table de la fenêtre.- À bas le recteur, les électeurs et les procureurs ! cria Joannes.- Il faudra faire, un feu de joie ce soir dans le Champ-Gaillard, poursuivit l'autre, avec les livres de maître Andry.- Et les pupitres des scribes ! dit son voisin.- Et les verges des bedeaux !- Et les crachoirs des doyens !- Et les buffets des procureurs !- Et les huches des électeurs !- Et les escabeaux du recteur !- À bas ! reprit le petit Jehan en faux-bourdon ; à bas maître Andry, les bedeaux et les scribes ; les théologiens, les médecins et les décrétistes ; les procureurs, les élect eurs et le recteur !- C'est donc la fin du monde ! murmura maître Andry en se bouchant les oreilles.- À propos, le recteur ! le voici qui passe dans la place, cria un de ceux de la fenêtre.Ce fut à qui se retournerait vers la place.- Est-ce que c'est v raiment notre vénérable recteur maître Thibaut ? demanda Jehan Frollo du Moulin qui, s'étant accroché à un pilier de l'intérieur, ne pouvait voir ce qui se passait au dehors.- Oui, oui, répondirent tous les autres, c'est lui, c'est bien lui, maître Thibau t le recteur.C'était en effet le recteur et tous les dignitaires de l'Université qui se rendaient processionnellement au-devant de l'ambassade et traversaient en ce moment la place du Palais. Les écoliers, pressés à la fenêtre, les accueillirent au passage avec des sarcasmes et des applaudissements ironiques. Le recteur, qui marchait en tête de sa compagnie, essuya la première bordée ; elle fut rude.- Bonjour, monsieur le recteur ! Holàhée ! bonjour donc !- Comment fait-il pour être ici, le vieux joueur ? Il a donc quitté ses dés ?- Comme il trotte sur sa mule ! elle a les oreilles moins longues que lui.- Holàhée ! bonjour, monsieur le recteur Thibaut ! Tybalde aleator! vieil imbécile ! vieux joueur !- Dieu vous garde ! avez-vous fait souvent double-six cette nuit ?- Oh ! la caduque figure, plombée, tirée et battue pour l'amour du jeu et des dés !- Où allez-vous comme cela, Tybalde ad dados, tournant le dos à l'Université et trottant vers la Ville ?- Il va sans doute chercher un logis rue Thibautodé, cria Jehan du Moulin.Toute la bande répéta le quolibet avec une voix de tonnerre et des battements de mains furieux.- Vous allez chercher logis rue Thibautodé, n'est-ce pas, monsieur le recteur, joueur de la partie du diable ?Puis ce fut le tour des autres dignitaires.- À bas les bedeaux ! à bas les massiers !- Dis donc, Robin Poussepain, qu'est-ce que c'est donc que celui-là ?- C'est Gilbert de Suilly, Gilbertus de Soliaco, le chancelier du collège d'Autun.- Tiens, voici mon soulier : tu es mieux placé que moi ; jette-le-lui par la figure.- Saturnalitias mittimus ecce nuces.- À bas les six théologiens avec leurs surplis blancs !- Ce sont là les théologiens ? Je croyais que c'étaient les six oies blanches données par Sainte-Geneviève à la ville, pour le fief de Roogny.- À bas les médecins !- À bas les disputations cardinales et quodlibétaires !- À toi ma coiffe, chancelier de Sainte-Geneviève ! tu m'as fait un passe-droit. - C'est vrai cela ! il a donné ma place dans la nation de Normandie au petit Ascanio Falzaspada, qui est de la province de Bourges, puisqu'il est Italien.- C'est une injustice, dirent tous les écoliers. À bas le chancelier de Sainte-Geneviève !- Ho hé ! maître Joachim de Ladehors ! Ho hé ! Louis Dahuille ! Ho hé ! Lambert Ho ctement !- Que le diable étouffe le procureur de la nation d'Allemagne !- Et les chapelains de la Sainte-Chapelle, avec leurs aumusses grises ; cum tunicis grisis !- Seu de pellibus grisis fourratis !- Holàhée ! les maîtres ès arts ! Toutes les belles chapes noires ! toutes les belles chapes rouges !- Cela fait une belle queue au recteur.- On dirait un duc de Venise qui va aux épousailles de la mer.- Dis donc, Jehan ! les chanoines de Sainte-Geneviève !- Au diable la chanoinerie !- Abbé Claude Choa rt ! docteur Claude Choart ! Est-ce que vous cherchez Marie la Giffarde ?。

The Majestic Beauty of Notre DameCathedral in ParisNotre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, also known as theCathedral of Our Lady, is one of the most magnificent and iconic buildings in the world. This majestic cathedral boasts of highly detailed and intricate architecture that hasinspired visitors for centuries.The construction of Notre Dame Cathedral began in the12th century, and it took almost two centuries to complete it, making it an incredibly well-preserved example of medieval Gothic architecture. The cathedral boasts of two 69-metertall towers and is adorned with stunning stained glass windows and delicate stone carvings. It is incredibly easy to get lost in the grandeur and magnificence of the building.Apart from its architecture, Notre-Dame Cathedral is also famous for its role in French history. The cathedral has witnessed some of the most significant events in French history, such as the coronation of Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte and the canonization of Joan of Arc.In 2019, a devastating fire broke out, causingsignificant damage to the cathedral’s roof and spire.However, repairs are ongoing, and the cathedral continues to welcome visitors.Notre-Dame Cathedral is open to visitors every day of the week, and it is an essential stop on any tourists’ itinerary in Paris. Visitors can climb the bell tower to get breathtaking panoramic views of the city, explore the cathedral’s interior, or attend mass. However, entrance fees apply, and visitors should remember to dress appropriately.In conclusion, Notre-Dame Cathedral is a magnificent building that should be on the bucket list of every traveler interested in architecture and history. Despite the recent damage, it remains an awe-inspiring monument to human creativity and perseverance. A visit to the cathedral is an unforgettable experience, and anyone who finds themselves in Paris should make sure to visit.。