2014年方重翻译竞赛-英译汉

- 格式:docx

- 大小:20.98 KB

- 文档页数:4

English-Chinese /English-Chinese TranslationWhat is translation?通俗的定义⏹《辞海》:把一种语言文字的意义用另一种语言文字表达出来。

⏹《牛津英语词典》:在保留意义的情况下从一种语言转变成另一种语言。

⏹I love you. 我爱你。

⏹Who are you? 你是谁?⏹Today is Monday. 今天是星期一。

⏹One boy is a boy, two boys half a boy, three boys no boy.⏹一个和尚挑水喝,两个和尚抬水喝。

三个和尚没水喝⏹他见马克思去了。

⏹He passed away.Word has its meaning in context.上课了?⏹Sauna⏹Pizza⏹Nike⏹Maxwell house⏹Jazz⏹Olay⏹The senator picked up his hat and courage.⏹参议员拾起了帽子,也鼓起了勇气文艺学的定义⏹从文艺学的角度解释翻译,认为翻译是艺术创作的一种形式,强调语言的创造功能,讲究译品的艺术效果Translation is art.⏹My dear father has joined the heavenly choir.⏹My dear father has passed away.⏹My father has died.⏹My old man has just kicked the bucket.⏹升天、过世、死了、翘辫子海上升明月,天涯共此时⏹Rising is the bright moon above the sea,Arising harmonious feeling you and me.⏹A round bright moon above the sea, a faraway homesickness you and me⏹Above the sea, the bright moon is hanging.In our hearts, the nostalgia is feeling.⏹Day after day he came to his work-sweeping, scrubbing, cleaning.Exercises影视片名的翻译transliteration 音译⏹Titanic⏹Mona Lisa⏹Hamletliteral translation 直译⏹My Fair Lady⏹The Graduate⏹Beauty and the Beast⏹Sleepless in Seattle⏹A Walk in the Clouds⏹Blood and Sand⏹The Silence of LampsFree translation 意译⏹Waterloo Bridge⏹Cloud Dancer⏹The Bathing Beauty⏹Gone with the Wind⏹The Red Shoes译名混乱⏹Ghost⏹Pretty Woman⏹Do the Right Thing⏹The House of the Spirits⏹The Sun Also RisesThe properties of translation⏹One servant, two masters⏹一仆二主Criteria of Translating⏹王佐良⏹一切照原作,雅俗如之,深浅如之,口气如之,文体如之。

初赛题:A. 汉译英部分:西方人所厌恶中国人的,其实不是信仰,而是不按原则办事、遇事喜欢抄近路走后门的办事习惯。

马克斯•韦伯所推崇的基督教新教伦理与资本主义精神在这个国家几乎连影儿也见不着。

这种令西方人不快的办事原则与信仰有直接联系,人们信奉的始终是所谓的“钱能通神”,只要“塞钱”给神仙并虔诚膜拜,神仙就会帮他们“走后门”,利用其的神通庇护信徒,保其仕途亨通或者财运发达。

而这一套与神仙进行“权钱交易”的习俗,则直接来自中国古代神权政治的传统。

《左传》中记师旷说:“夫君,神之主也,而民之望也。

”这就是说,统治者的身份是介于人神之间的。

就因为这种半人半神,或者叫不人不神的身份,所以人人都得“信于神”。

因为一旦做不好,就是“小信未孚,神弗福也”,国家的灾祸就离得不远了。

你看,连一国的统治者都要畏于神的权威时不时对神仙进行贿赂,何况匹夫匹妇哉?(359字)B. 英译汉部分:History is about more than imparting life skills: it is about life. It is the skill to collate and assess evidence, to form a geography of time and a sense of our place within that map. This requires not bite-size, easily digestible lumps of historical knowledge – what Gordon Marsden has called the Yo! Sushi style of history – but a rolling tale with a beginning, middle and end, and a future.Yes, history is one damn thing after (and before) another, because events and people, periods and thoughts, all have antecedents and consequences, a series of smaller, interconnecting stories within an overarching narrative.Maths and spelling are useful, but not essential (I have coped without them, just); to live without a sense of history, however, would be a true debility. The debate over what should be on the curriculum is endless and insoluble, as it ought to be. Should there be fewer white men and 20th-century dictators taught in school? More Gandhi and less Churchill? History in school is often depressingly moralising, a set of cautionary tales. Nazis and slavery: bad. Women’s Rights and William Wilberforce: good.These are all important considerations, but secondary to persuading a new generation that history has a deeper intrinsic value than teaching morality or multicultural awareness. History is about gaining self-knowledge, and knowledge of the living, by getting to know the dead.Although the quality of history teaching in British schools is generally high, the study of history is narrowing and dwindling at the very moment when it is most needed. Instead of being corralled into a few, restricted subjects and penalised for straying from the prescribed path, pupils should be rewarded whenever they plunge into the historical undergrowth. History does not teach anything in particular; it teaches everything, and it is worth far more to a schoolchild’s spiritual health than one hour a week. (310 words)。

The Alternate LifeThe alternate life is the consequence of the communications revolution of the last 30 years or so. There is another, highly competitive educational system, opposed in almost every essential way to traditional schooling, that operates on the child and youth from the age of 2. It takes up as much of his time as the school does, and it works on him with far greater effectiveness.That system is the linked structure of which television is the heart and which numbers among its constituents film, radio, comic books, pop music, sports—and the life styles (including the drug culture, permissive sex, and systematized antisocial conduct) which this structure either automatically or deliberately produces.This alternative life is a life; it is not a diversion, a hobby, an amusement. It offers its own disciplines, its own curriculum, its own ethical and cultural values, its own style and language. It works on children and youths every day, year after year, teaching them, forming them, conditioning them. And it is profoundly opposed to traditional education. There is no way of reconciling the values of literature or science with the values of the TV commercial. There is no way of reconciling the vision offered by Shakespeare or Newton with the vision of life offered by the ―Gong Show‖. Two systems of thought and feeling stand opposed to each other.This has never before been the case. The idea of education was never before opposed by a competitor. It was taken for granted because no alternative appeared on the horizon. But today there is a complete alternative life to which children submit themselves. This alternative life offers them heroes, slogans, images, forms of conduct, and content of a sort—and all run counter to the message given in the classroom.For the first time in history, the child is required to be a citizen of two cultures: the tradition and the alternate life. Is it any wonder that such a division of loyalties should result in the chaos we observe? In a deep sense, all our children (and, to adegree, our teachers, our parents, and ourselves) are schizophrenics. On the one hand is the reality-system expounded in a book, the idea, the cultural past; on the other hand is the far more vivid and comprehensible reality-system expounded by television, the rock star, the religion of instantaneous sensation, gratification and consumption.Good teachers, when you question them inexorably, almost always finally admit that their difficulties stem from the competition of the alternate life. And this competition they are not trained to meet. The alternate life has one special psychological effect that handicaps the teacher—any teacher, whether of writing or any other basic subject. That effect is a decline in the faculty of attention, and therefore a decline in the capacity to learn—not the innate capacity, but the capacity as it is conditioned by the media.This conception of the alternate life is probably debatable, and it certainly will not be accepted by everyone. Its claim to the interest of others, if not their agreement, lies in the fact that it goes beyond the present educational system and tries to locate the ultimate source of our troubles in the changes now agitating our entire Western culture.(节选自The Short Prose Reader (second edition) by Gilbert H. Muller and Harvey S. Wiener, McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1982。

湖北省翻译大赛非专业a组决赛试题及答案湖北省翻译大赛非专业A组决赛试题及答案一、英译汉1. The rapid development of technology has significantly changed the way we live and work.答案:技术的快速发展显著改变了我们的生活方式和工作方式。

2. Environmental protection is a global issue that requires the cooperation of all countries.答案:环境保护是一个需要所有国家合作的全球性问题。

二、汉译英1. 随着互联网的普及,人们获取信息的方式越来越多样化。

答案:With the popularization of the Internet, the ways in which people access information are becoming increasingly diverse.2. 教育是提高一个国家综合国力的关键因素之一。

答案:Education is one of the key factors in improving a country's comprehensive national strength.三、段落翻译1. In recent years, the concept of a "smart city" has gained popularity. A smart city is one that uses digital technology to improve the quality of life for its residents, enhance the efficiency of urban operations and services, and promote sustainable development.答案:近年来,“智慧城市”的概念越来越受欢迎。

第十届CASIO杯翻译竞赛英语组原文Humans are animals and like all animals we leave tracks as we walk:signs of passage made in snow,sand,mud,grass,dew,earth or moss.The language of hunting has a luminous word for such mark-making:‘foil’.A creature’s‘foil’is its track.We easily forget that we are track-makers,though,because most of our journeys now occur on asphalt and concrete–and these are substances not easily impressed.Always,everywhere,people have walked,veining the earth with paths visible and invisible,symmetrical or meandering,’writes Thomas Clark in his enduring prose-poem‘In Praise of Walking’.It’s true that,once you begin to notice them,you see that the landscape is still webbed with paths and footways–shadowing the modern-day road network,or meeting it at a slant or perpendicular.Pilgrim paths, green roads,drove roads,corpse roads,trods,leys,dykes,drongs,sarns,snickets–say the names of paths out loud and at speed and they become a poem or rite–holloways,bostles,shutes,driftways,lichways,ridings,halterpaths,cartways,carneys, causeways,herepaths.Many regions still have their old ways,connecting place to place,leading over passes or round mountains,to church or chapel,river or sea.Not all of their histories are happy.In Ireland there are hundreds of miles of famine roads,built by the starving during the1840s to connect nothing with nothing in return for little,unregistered on Ordnance Survey base maps.In the Netherlands there are doodwegen and spookwegen–death roads and ghost roads–which converge on medieval cemeteries. Spain has not only a vast and operational network of cañada,or drove roads,but also thousands of miles of the Camino de Santiago,the pilgrim routes that lead to the shrine of Santiago de Compostela.For pilgrims walking the Camino,every footfall is doubled,landing at once on the actual road and also on the path of faith.In Scotland there are clachan and rathad–cairned paths and shieling paths–and in Japan the slender farm tracks that the poet Bashōfollowed in1689when writing his Narrow Road to the Far North.The American prairies were traversed in the nineteenthcentury by broad‘bison roads’,made by herds of buffalo moving several beasts abreast,and then used by early settlers as they pushed westwards across the Great Plains.Paths of long usage exist on water as well as on land.The oceans are seamed with seaways–routes whose course is determined by prevailing winds and currents–and rivers are among the oldest ways of all.During the winter months,the only route in and out of the remote valley of Zanskar in the Indian Himalayas is along the ice-path formed by a frozen river.The river passes down through steep-sided valleys of shaley rock,on whose slopes snow leopards hunt.In its deeper pools,the ice is blue and lucid.The journey down the river is called the chadar,and parties undertaking the chadar are led by experienced walkers known as‘ice-pilots’,who can tell where the dangers lie.Different paths have different characteristics,depending on geology and purpose. Certain coffin paths in Cumbria have flat‘resting stones’on the uphill side,on which the bearers could place their load,shake out tired arms and roll stiff shoulders;certain coffin paths in the west of Ireland have recessed resting stones,in the alcoves of which each mourner would place a pebble.The prehistoric trackways of the English Downs can still be traced because on their close chalky soil,hard-packed by centuries of trampling,daisies flourish.Thousands of work paths crease the moorland of the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides,so that when seen from the air the moor has the appearance of chamois leather.I think also of the zigzag flexure of mountain paths in the Scottish Highlands,the flagged and bridged packhorse routes of Yorkshire and Mid Wales,and the sunken green-sand paths of Hampshire on whose shady banks ferns emerge in spring,curled like crosiers.The way-marking of old paths is an esoteric lore of its own,involving cairns, grey wethers,sarsens,hoarstones,longstones,milestones,cromlechs and other guide-signs.On boggy areas of Dartmoor,fragments of white china clay were placed to show safe paths at twilight,like Hansel and Gretel’s pebble trail.In mountain country,boulders often indicate fording points over rivers:Utsi’s Stone in the Cairngorms,for instance,which marks where the Allt Mor burn can be crossed toreach traditional grazing grounds,and onto which has been deftly incised the petroglyph of a reindeer that,when evening sunlight plays over the rock,seems to leap to life.Paths and their markers have long worked on me like lures:drawing my sight up and on and over.The eye is enticed by a path,and the mind’s eye also.The imagination cannot help but pursue a line in the land–onwards in space,but also backwards in time to the histories of a route and its previous followers.As I walk paths I often wonder about their origins,the impulses that have led to their creation, the records they yield of customary journeys,and the secrets they keep of adventures, meetings and departures.I would guess I have walked perhaps7,000or8,000miles on footpaths so far in my life:more than most,perhaps,but not nearly so many as others.Thomas De Quincey estimated Wordsworth to have walked a total of 175,000–180,000miles:Wordsworth’s notoriously knobbly legs,‘pointedly condemned’–in De Quincey’s catty phrase–‘by all…female connoisseurs’,were magnificent shanks when it came to passage and bearing.I’ve covered thousands of foot-miles in my memory,because when–as most nights–I find myself insomniac,I send my mind out to re-walk paths I’ve followed,and in this way can sometimes pace myself into sleep.‘They give me joy as I proceed,’wrote John Clare of field paths,simply.Me too.‘My left hand hooks you round the waist,’declared Walt Whitman–companionably, erotically,coercively–in Leaves of Grass(1855),‘my right hand points to landscapes of continents,and a plain public road.’Footpaths are mundane in the best sense of that word:‘worldly’,open to all.As rights of way determined and sustained by use,they constitute a labyrinth of liberty,a slender network of common land that still threads through our aggressively privatized world of barbed wire and gates,CCTV cameras and‘No Trespassing’signs.It is one of the significant differences between land use in Britain and in America that this labyrinth should exist.Americans have long envied the British system of footpaths and the freedoms it offers,as I in turn envy the Scandinavian customary right of Allemansrätten(‘Everyman’s right’).This convention–born of a region that did not pass through centuries of feudalism,andtherefore has no inherited deference to a landowning class–allows a citizen to walk anywhere on uncultivated land provided that he or she cause no harm;to light fires;to sleep anywhere beyond the curtilage of a dwelling;to gather flowers,nuts and berries; and to swim in any watercourse(rights to which the newly enlightened access laws of Scotland increasingly approximate).Paths are the habits of a landscape.They are acts of consensual making.It’s hard to create a footpath on your own.The artist Richard Long did it once,treading a dead-straight line into desert sand by turning and turning about dozens of times.But this was a footmark not a footpath:it led nowhere except to its own end,and by walking it Long became a tiger pacing its cage or a swimmer doing lengths.With no promise of extension,his line was to a path what a snapped twig is to a tree.Paths connect.This is their first duty and their chief reason for being.They relate places in a literal sense,and by extension they relate people.Paths are consensual,too,because without common care and common practice they disappear:overgrown by vegetation,ploughed up or built over(though they may persist in the memorious substance of land law).Like sea channels that require regular dredging to stay open,paths need walking.In nineteenth-century Suffolk small sickles called‘hooks’were hung on stiles and posts at the start of certain wellused paths: those running between villages,for instance,or byways to parish churches.A walker would pick up a hook and use it to lop off branches that were starting to impede passage.The hook would then be left at the other end of the path,for a walker coming in the opposite direction.In this manner the path was collectively maintained for general use.By no means all interesting paths are old paths.In every town and city today, cutting across parks and waste ground,you’ll see unofficial paths created by walkers who have abandoned the pavements and roads to take short cuts and make asides. Town planners call these improvised routes‘desire lines’or‘desire paths’.In Detroit –where areas of the city are overgrown by vegetation,where tens of thousands of homes have been abandoned,and where few can now afford cars–walkers and cyclists have created thousands of such elective easements.第十届CASIO杯翻译竞赛英语组参考译文路[英]罗伯特·麦克法伦作侯凌玮译人是一种动物,因而和所有其他动物一样,我们行走时总会留下踪迹:雪地、沙滩、淤泥、草地、露水、土壤和苔藓上都有我们经过的痕迹。

练习1 美国印象☐我恐怕不能把美国描绘成十足的天堂——从一般角度来说,也许我对这个国家所知甚少。

我说不出它的经度或纬度;我算不出它出产谷物的价值;我对它的政治也不十分熟悉。

这些东西可能不会使你感兴趣,它们当然也不会让我感兴趣。

☐在美国上岸后得到的第一个深刻印象,就是美国人可能算不上世界上穿得最漂亮的,但却是穿得最舒服的。

那里看得到男人头戴着不堪入目的烟囱式高顶礼帽,但很少有不戴帽子的男人;还看到穿着难看至极的燕尾服的男人,但很少有不穿外套的男人。

美国人的穿戴显得舒适,这和在我国常可以看到的人们衣衫褴褛的情形形成了鲜明的对比。

☐我特别注意到的第二个特点是,似乎每个人都在急着赶火车。

这种情形对诗歌和浪漫爱情是不利的。

要是罗密欧和朱丽叶老是为乘火车而担心,或是在为返城车票而烦恼,莎士比亚就不可能写出那几幕如此富有诗意与伤感情调的阳台戏了。

☐美国是世界上最嘈杂的国家。

在早晨,不是夜莺的歌声,而是汽笛的呜叫把人们唤醒。

美国人讲求实际的头脑这么健全,却没有想到要降低这种令人难以忍受的噪音,真叫人吃惊。

所有艺术都依赖于精细微妙的敏锐感觉,这样持续不断的喧嚣,最终一定会损害人的音乐天赋。

☐美国城市没有牛津、剑桥、索尔兹伯里和温彻斯特那么美丽,那些地方有优雅时代的美好遗迹;虽然不时还是可以看到许多美的东西,但只能在美国人没有存心创造美的地方。

在美国人有意创造美的地方,他们显然没有成功。

美国人的突出特点,便是他们把科学应用于现代生活的那种态度。

☐在纽约走马观花地一走,这一点就一目了然了。

在英国人们常把发明家视作狂人,发明带来的是失望与穷困的例子简直不胜枚举。

在美国发明家受到尊重,他随时可以得到人们的帮助。

在那里心灵手巧、把科技应用于人类的劳动,是致富的捷径。

没有一个国家比美国更爱机器的了。

☐或许,值得指出的是,被许多人指为美国式英语的其实是老的英国式表达,它们在我国已经消失,却在我们的殖民地里留存下来。

许多人以为美国人常说的“I guess”(“我猜”)纯粹是一种美国式表达,但约翰∙洛克在他的The understanding (《理解论》)中就用过这种说法,就像我们现在使用“I think”(“我想”)一样。

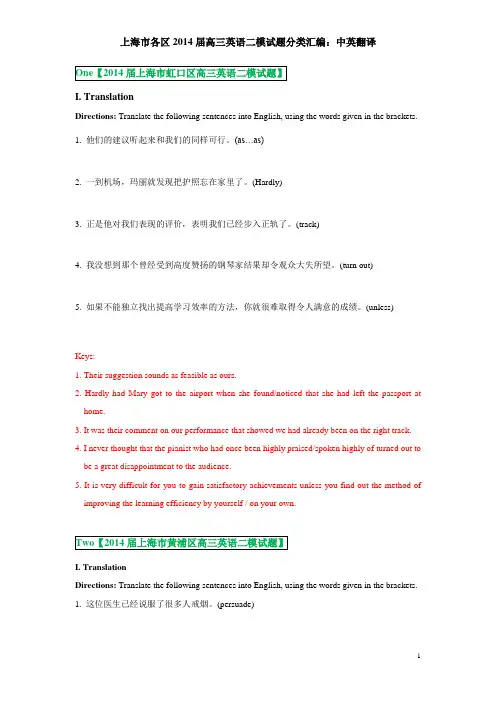

I. TranslationDirections: Translate the following sentences into English, using the words given in the brackets.1. 他们的建议听起来和我们的同样可行。

(as…as)2. 一到机场,玛丽就发现把护照忘在家里了。

(Hardly)3. 正是他对我们表现的评价,表明我们已经步入正轨了。

(track)4. 我没想到那个曾经受到高度赞扬的钢琴家结果却令观众大失所望。

(turn out)5. 如果不能独立找出提高学习效率的方法,你就很难取得令人满意的成绩。

(unless)Keys:1. Their suggestion sounds as feasible as ours.2. Hardly had Mary got to the airport when she found/noticed that she had left the passport at home.3. It was their comment on our performance that showed we had already been on the right track.4. I never thought that the pianist who had once been highly praised/spoken highly of turned out to be a great disappointment to the audience.5. It is very difficult for you to gain satisfactory achievements unless you find out the method of improving the learning efficiency by yourself / on your own.I. TranslationDirections: Translate the following sentences into English, using the words given in the brackets.1. 这位医生已经说服了很多人戒烟。

中译英天衢丹阙:老北京风物图卷首都北京,是国家历史文化名城,世界著名古都。

千年帝京,六朝故都,保存了极其丰富的文物古迹、自然景观和丰富的文化内涵与非物质文化遗产。

著名建筑学家梁思成先生曾称之为现存世界上最伟大之中古都市。

其中尤以南起永定门北至钟鼓楼,全长7.8公里的中轴线,世界上绝无仅有,充分展现了古都北京城市的特点和中华悠久历史文化的魅力。

画家刘洪宽先生怀着对老北京的深厚情感和对古都的热爱,花甲之年,创作了这幅50余米的国画。

他凭借儿时记忆,实地写生和查阅历史资料,由南到北,再现了老北京中轴线上的人情风物,历经五年心血筑成,令人敬服。

他笔下的老北京古韵犹存,街道商铺、行人市景与老城门城墙交相辉映,这可谓现代版的《清明上河图》,呈现了一幅美丽的可以“触摸历史”的宏大画卷。

最近北京市领导已经正式宣布了把这条中轴线申报世界文化遗产。

我想,这幅画卷定会为申遗增色。

画家作者知我60多年来,一直为古都的保护奔走于古城内外、大街小巷和中轴线上,与古都结下了深厚的情缘,特嘱我为序。

于是写了几句知语感言,权以充之,并借以为画卷出版之祝贺。

至于画中的精美图景和丰富的文化内涵,还请高明观者自己去观赏和评说,在此不作多赘。

Old City of Beijing: Its Grandeur and SplendorsBeijing, capital city of China, boasts the longest history as a well-known ancient capital city in the world. Presently, it is the most well-known historical and cultural in China. As the capital of six dynasties for over 1,000 years, it is home to a world of historic relics, natural landscapes, cultural profundity and intangible cultural heritages. Mr. Liang Sicheng, a celebrated architect, called it the greatest ancient capital city existent in the world. The most typical of the city's splendors is the 7.8-kilometer axis, which starts at Yongding Gate in the south and ends with the Bell Drum Tower in the north. It well features Beijing as an ancient capital city full of charm of its splendid Chinese culture.Mr. Liu Hongkuan, a painter who had cherished profound love for the old city of Beijing, created this over 50-meter-long Chinese-style scroll entitled Old City of Beijing: Its Grandeur and Splendors in his 60s. Based on his childhood recollections, his sketch from nature and his review of historical records, he reproduced the grandeur and splendors along the axis in the scroll over a span of five years, an admirable conduct indeed. In the scroll, he portrayed Beijing as an ancient city of everlasting profundity with streets, shops, passers-by and bazaars in perfect harmony with its old gates and old walls, making his scroll a modern version of Riverside Scene at Qingming Festival, an artistic work by a Song Dynasty painter. The scroll offers easy access to the historical beauties and majesties of the old city of Beijing.Recently, leaders of the Beijing Municipal government have officially announced that they will file an application for world cultural heritage for this axis. It is my firm conviction that this scroll will serve as a great boost for the successful application.For over 60 years of my acquaintance with him, Mr. Liu has been endeavoring to protect the old city of Beijing through going into and outside of the city and walking around city streets and Hutongs and along the axis. And by so doing, he has cultivated a profound love for this ancient capital. He once urged me to write a preface for this artistic work and here, I just write a few words about what I feel for the moment and intend it as my congratulations on the publication of this scroll. As to the spectacular landscapes in the scroll and their profound cultural connotations, I think our readers will surely be able to decode them and appreciate them.。

2014年6月英语四级翻译真题及答案翻译一:大四生活现在大学生的学习压力相当重。

除了大四,他们开始找工作了,其余的学生总是忙于学习,而不愿参加校园团体和俱乐部,不愿参加体育锻炼和其他课外活动,不愿与他们的朋友玩玩,不愿关心和学习没有关系的事。

总之,他们就像一个机器人。

压力大,时间少,功课多。

看到同寝室里的人都上图书馆去学习,到深夜闭馆才回,而自己却去看电影,他们就会有一种内疚感。

一想到白天什么事都没干,心里就感到不安,会整夜因此睡不着觉。

他们学习太紧张,几乎没有时间好好品尝生活,干些其他事,成为一个全面发展的人。

读大学使他们失去太多的个人幸福和健康。

参考译文College studentsnow bear heavy academic pressure. You will find them—except seniors who arebeginning to look for a job—always too busy in studies to join campusorganizations, too busy to take part in sports and other extracurricularactivities, too busy to share the interests of their friends and too busy topay attention to anything that is not connected with their studies. In shortthey have become nothing but a robot. They are under pressure to do too muchwork in too little time. If their roommates are studying in the library untilit closes at midnight while they go to a movie they will feel guilty. The veryidea of doing nothing during the day will make them uncomfortable and sleeplessall night. They study so hard that they have hardly had time to savor life andto pursue other interests to grow as well-rounded people. The pursuit ofcollege education costs them too much personal happiness and health.翻译二:人物介绍徐霞客一生周游考察了十六个省,足迹几乎遍及全国。

英译汉原文:Are We There Yet?America’s recovery will be much slower than that from most recessions; but the government can help a bit.“WHITHER goest thou, America?” That question, posed by Jack Kerouac on behalf of the Beat generation half a century ago, is the biggest uncertainty hanging over the world economy. And it reflects the foremost worry for American voters, who go to the polls for the congressional mid-term elections on November 2nd with the country’s unemployment rate stubbornly stuck at nearly one in ten. They should prepare themselves for a long, hard ride. The most wrenching recession since the 1930s ended a year ago. But the recovery—none too powerful to begin with—slowed sharply earlier this year. GDP grew by a feeble 1.6% at an annual pace in the second quarter, and seems to have been stuck somewhere similar since. The housing market slumped after temporary tax incentives to buy a home expired. So few private jobs were being created that unemployment looked more likely to rise than fall. Fears grew over the summer that if this deceleration continued, America’s economy would slip back into recession. Fortunately, those worries now seem exaggerated. Part of the weakness of second-quarter GDP was probably because of a temporary surge in imports from China. The latest statistics, from reasonably good retail sales in August to falling claims for unemployment benefits, point to an economy that, though still weak, is not slumping further. And history suggests that although nascent recoveries often wobble for a quarter or two, they rarely relapse into recession. For now, it is most likely that America’s economy will crawl along with growth at perhaps 2.5%: above stall speed, but far too slow to make much difference to the jobless rate. Why, given that Am erica usually rebounds from recession, are the prospects so bleak? That’s because most past recessions have been caused by tight monetary policy. When policy is loosened, demand rebounds. This recession was the result of a financial crisis. Recoveries after financial crises are normally weak and slow as banking systems are repaired and balance-sheets rebuilt. Typically, this period of debt reduction lasts around seven years, which means America would emerge from it in 2014. By some measures, households are reducing their debt burdens unusually fast, but even optimistic seers do not think the process is much more than half over.Battling on the busAmerica’s biggest problem is that its politicians have yet to acknowledge that the economy is in for such a long, slow haul, let alone prepare for the consequences. A few brave officials are beginning to sound warnings that the jobless rate is likely to “stay high”. But the political debate is more about assigning blame for the recession than about suggesting imaginative ways to give more oomph to the recovery. Republicans argue that Barack Obama’s shift towards “big government” explains the economy’s weakness, and that high unemployment is proof that fiscal stimulus was a bad idea. In fact, most of the growth in government to date has been temporary and unavoidable; the longer-run growth in government is more modest, and reflects the policies of both Mr Obama and his predecessor. And the notion that high joblessness “proves” that stimulus failed is simply wrong. Th e mechanicsof a financial bust suggest that without a fiscal boost the recession would have been much worse. Democrats have their own class-warfare version of the blame game, in which Wall Street’s excesses caused the problem and higher taxes on high-earners are part of the solution. That is why Mr. Obama’s legislative priority before the mid-terms is to ensure that the Bush tax cuts expire at the end of this year for households earning more than $250,000 but are extended for everyone else. This takes an unnecessary risk with the short-term recovery. America’s experience in 1937 and Japan’s in 1997 are powerful evidence that ill-timed tax rises can tip weak economies back into recession. Higher taxes at the top, along with the waning of fiscal stimulus and belt-tightening by the states, will make a weak growth rate weaker still. Less noticed is that Mr. Obama’s fiscal plan will also worsen the medium-term budget mess, by making tax cuts for the middle class permanent.Ways to overhaul the engineIn an ideal world America would commit itself now to the medium-term tax reforms and spending cuts needed to get a grip on the budget, while leaving room to keep fiscal policy loose for the moment. But in febrile, partisan Washington that is a pipe-dream. Today’s g oals can only be more modest: to nurture the weak economy, minimize uncertainty and prepare the ground for tomorrow’s fiscal debate. To that end, Congress ought to extend all the Bush tax cuts until 2013. Then they should all expire—prompting a serious fiscal overhaul, at a time when the economy is stronger.A broader set of policies could help to work off the hangover faster. One priority is to encourage more write-downs of mortgage debt. Almost a quarter of all Americans with mortgages owe more than their houses are worth. Until that changes the vicious cycle of rising foreclosures and falling prices will continue. There are plenty of ideas on offer, from changing the bankruptcy law so that judges can restructure mortgage debt to empowering special trustees to write down loans. They all have drawbacks, but a fetid pool of underwater mortgages will, much like Japan’s loans to zombie firms, corrode the financial system and harm the recovery. Cleaning up the housing market would help cut America’s unemployment rate, by making it easier for people to move to where jobs are. But more must be done to stop high joblessness becoming entrenched. Payroll-tax cuts and credits to reduce the cost of hiring would help. (The health-care reform, alas, does the opposite, at least for small businesses.) Politicians will also have to think harder about training schemes, because some workers lack the skills that new jobs require. Americans are used to great distances. The sooner they, and their politicians, accept that the road to recovery will be a long one, the faster they will get there.译文:我们到达目的地了吗?与大多数衰退之后的复苏相比,这次美国经济的复苏会慢得多。

中国诗词翻译大赛英文作文英文回答:China Poetry Translation Contest: A Bridge Building Exercise。

The China Poetry Translation Contest (CPTC) is a prestigious international poetry competition that aims to promote Chinese poetry and foster cultural exchange between China and the rest of the world. It invites poets, translators, and poetry enthusiasts from around the globe to submit their translations of Chinese poems into their native languages.The contest was founded in 2011 by the China Foreign Languages Publishing Administration (FPLA) and has since become a major event in the global literary landscape. It has attracted the participation of renowned poets and translators such as Seamus Heaney, Charles Bernstein, Bei Dao, and Yu Guangzhong.The CPTC offers an invaluable platform for aspiring and established translators to showcase their skills and contribute to the dissemination of Chinese poetry worldwide. It also provides an opportunity for readers to appreciate the beauty and depth of Chinese literature.The rigorous selection process ensures that the winning translations are not only accurate and faithful to the original poems but also possess literary merit in their own right. The judges for the CPTC are experts in Chinese literature, translation, and poetry.The contest has played a significant role in promoting cultural exchange between China and the world. It has fostered a greater understanding of Chinese poetry and culture among the international community. The translated poems have been widely published in literary journals, anthologies, and online platforms, reaching a global audience.中文回答:中国诗歌翻译大赛,架设沟通桥梁。

“英译汉”- Hair in Your Eyes障目之发(美)海伦·福斯特·斯诺我一直不明白,有些人为何要让头发垂下来挡住眼睛。

我不喜欢任何东西遮住我的视线,哪怕是一根发丝都令我烦扰。

留那种蓬松的刘海,我是可以理解的。

1925年流行西瓜头短发,我也不时地剪过那种发型。

(从前,我们还用肥皂将脸颊两边的发梢卷起。

)二十世纪六十年代,男士和男孩儿留起了女性十足的长发,把自己藏在长发之后。

他们的刘海很长,就像一吊薄薄的帘子,几乎遮住了双眼。

这意味着什么呢?无非是要显得蓬乱不修——即便是刻意整饰,也要看似蓬乱,浪漫不羁。

后来,我发现了这种发型的缘由:无论男孩或女孩,都不时地向后拢头发。

他们有时会摇摇头,让那些头发再次耷拉下来。

这样,他们就可以伸手把头发重新拢到后面去。

这种姿势,女性气十足,在紧张和局促不安之时,能起到自我镇定的作用,不至于手足无措。

电视上的雪儿[1]就是一个例子。

她头发又长又直,从中间一分为二,垂吊在脸颊两边,常常把双眼几乎遮住了一半。

她只好不时地用头往后甩长发,或举手撩开眼前刘海——这一动作,很快就成为“雪儿范儿”。

显而易见,虽然她常常有点儿故作姿态,雪儿却以为这种动作能够彰显她个人的魅力与个性。

众所周知,从古到今,痴迷发型是表现人性的主要方式之一。

人们甩动头发,犹如挥舞旗帜,向他人挑战。

长发披肩,蓬乱不修的风格,受到一代又一代艺术家、音乐家、演员及其他特立独行的人们的热捧,成为他们超凡脱俗的标志。

波士顿大众乐团的日籍指挥家[2]就是一个例子——他总把鬃毛似的长发甩过来甩过去,浓密的刘海几乎遮住了他的双眼,而他却透过刘海向外窥视。

所有的指挥家都青睐狮子般的长发。

然而,留长发遮挡视线、把自己掩藏在发后是一回事,甩长发却是另一回事了。

有一次,我鼻子流血,去耶鲁大学纽黑文医院急诊室。

为我接诊的是一位实习医生——一位年轻的日裔女子,留着一头又厚又密的短发。

浓密的刘海太长,遮住了她的视线。

英汉互译的三种基本方法上海理工大学教授,第十四、第十五届韩素音青年翻译奖竞赛汉译英三等奖、英译汉二等奖获得者张顺生1999年笔者到高校工作以后,参加了第十四届和第十五届韩素音青年翻译竞赛。

参加第十四届竞赛纯属偶然,竞赛截止的几天前我刚好浏览了《中国翻译》杂志,不经意间读到了上面刊登的竞赛活动,其中汉译英“想起清华种种”不长,自己特感兴趣,因此连忙回家认真翻译了初稿,后来又校对了几遍,便投了出去。

没想到竞幸运地获得了三等奖。

第十五届韩素音青年翻译竞赛汉译英我虽未获奖,英译汉却幸运地获得了二等奖。

我对第十五届韩素音青年翻译竞赛的印象非常深刻,比如汉译英的题目“常想一二,不思八九”的翻译,我当时的翻译为“Always Bear in Mind the Few Happy Things,Never Take to Heart the Many Unhappy Ones”,而对英译汉的题目“A Person Who Apologises Has the Moral Ball in His Court”(参考译文译作“谁给别人道歉,谁就在道义上掌握了主动”)的翻译,当时也颇费周折,我觉得汉译宜简洁些,故经再三考虑,将其译作“主动道歉理不亏”。

两次参赛荣幸获奖提振了我对英汉互译的信心,也点燃了我对翻译的兴趣。

近年来我不仅一直鼓励学生参加韩素音青年翻译奖竞赛,还举办了两次校级翻译竞赛,出了2014年姑苏区翻译竞赛试题。

从事翻译和翻译教学工作过程中,自己也有一些心得体会,籍此机会跟大家分享一下。

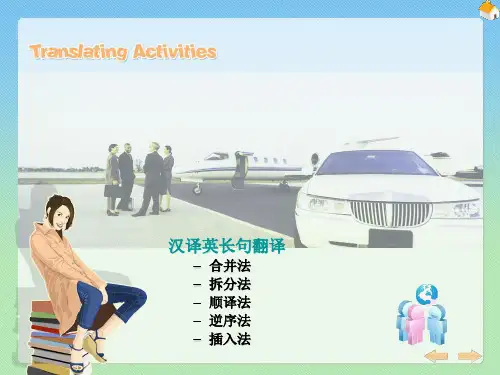

以往的翻译方法多是从“直译和意译”和“归化和异化”等角度而谈的,我这里则想从译语与源语的关系来探讨英汉互译方法。

我认为英汉互译基本方法有三种,即直接套用、结构模仿和融会创新。

一、直接套用所谓“直接套用”指翻译时如能采用“拿来主义”的即采用“拿来主义”,不必另起炉灶,尤其是单词、词组和句子层面。

比如,翻译“石头剪子布”就可以直接将英语中对应的词找出,直接套用英语中的rock- paper-scissors;“口水战”可套用英语中的a war of words;游戏“打水漂”可套用英语中的词组play ducks and drakes;“傻人有傻福”可套译为Fortune favors fools;“谋事在人,成事在天”可套译为Man proposes, God disposes;从交际角度而言“人非圣贤,孰能无过”可视具体情况套用蒲柏(Alexander Pope,1688-1744) 的To err is human或Even Homer sometimes nods;翻译“喊破嗓子,不如甩开膀子”时孙宁巧妙地套用了英语中的“Talking the talk is not as good as walking the walk”。

2014年4月高等教育自学考试全国统一命题考试英语(二)试卷(课程代码00015)阅读判断全文翻译及重点Running:sport or way of life?跑步:运动还是生活方式?1)You go through1the channels2several times and find that once again3there’s nothing on TV that interests you.Not a problem!Just put on4some running shoes and comfortable5clothes and go for a run.【译文】你浏览了好几次频道,发现电视上还是没有你感兴趣的。

这不是个问题!穿上跑鞋和舒适的衣服出去跑跑步吧。

【重点掌握】1.go through:经历;度过;通读2.channel:n.(电视)频道;波段;渠道;方法;沟渠;航道;海峡;v.将(精力或情感)专注于;输送(资金)3.once again:再次;再度;从头4.put on:表演(节目),举办,展出,增加(体重)fortable:adj.舒适的;愉快轻松的;宽裕的;轻松领先的;自信的;(伤者)情况稳定的;无忧无虑的2)One of the best things about the sport of running is that you don’t need expensive1equipment2.All you need is a good pair of3running shoes and a safe environment.But don’t be fooled into thinking the sport of running is easy.It requires discipline4and concentration5.【译文】跑步运动最棒的一点是你不需要昂贵的设备。

A Way of LifeFellow students: 同学们:Every man has a philosophy of life in thought, in word, or in deed, workedout in himself unconsciously. 每个人都有他的生活哲学,无论是在思想,言语还是在行为中,而且这哲学会不自觉地在他身上发挥着作用。

In possession of the very best, he may not know of its existence; with the very worst he may pride himself as a paragon. 心怀上佳的哲思,他可能不会知晓它的存在;心存至陋之哲理,他却可能自诩为楷模。

As it grows with the growth it cannot be taught to the young in formal lectures.它随着人的成长而增加,非正式的演讲所能授予年轻人。

What have bright eyes, red blood, quick breath and taut muscles to do with philosophy? 明眸,鲜血,急促的呼吸,紧实的肌肉,这些与哲学何干?Did not the great Stagirite say that young men were unfit students of it? 难道伟大的斯塔利亚人不曾讲过,年轻人是它不合格的学生?– they will hear as though they heard not, and to no profit. 他们会充耳不闻,了无裨益。

Why then should I trouble you?那我又为何来烦扰你?Because I have a message that may be helpful. 因为我有一言,或可助你。

It is not philosophical, nor is it strictly moral or religious, one or other of which I was told my address should be, and yet in a way it is all three. 它无关哲学,也非完全有关道德或宗教,亦非我的演讲所被要求谈到的某些东西,然而从某种意义上说它三者均是。

It is the oldest and the freshest, the simplest and the most useful, so simple indeed is it that some of you may turn away disappointed as was Naaman the Syrian when told to go wash in Jordan and be clean. 它最陈旧也最新鲜,最简单也最实用,简单得你们中有人会转身离去,心中失望,就像叙利亚的纳曼被告知沐浴于约旦可得洁净时那样。

You know those composite tools to be bought for 50 cents, with one handle to fit a score of more of instruments. 你知道那些用50分能买到的组装工具,它有一个手柄,用来修理那些大件。

The workmanship is usually bad, so bad, as a rule, that you will not find an example in any good carpenter's shop; 做工通常很差,以至于按规矩你在任何好工匠的店铺里都找不出一个来。

but the boy has one, the chauffeur slips one into his box, and the sailor into his kit, and there is one in the odds-and-ends drawer of the pantry of every well-regulated family. 但是男孩子会备着一个,司机会往他的盒子里塞一个,水手会在他的工具箱里放一个,每一个个井井有条的家庭也会在餐具室的杂物抽屉里存着一个。

It is simply a handy thing about the house, to help over the many little difficulties of the day. 它只是家里的一个顺手的东西,用来搞定日常琐碎的小困难。

Of this sort of philosophy I wish to make you a present – a handle to fit your life tools.我希望以这样的哲学赠你一个礼物——一个修理你人生之工具的手柄。

Whether the workmanship is Sheffield or shoddy, this helve will fit anything from a hatchet to a corkscrew. 不管做工是精湛还是极烂,这个手柄都能修好一切,从短柄斧到螺丝锥。

My message is but a work, a Way, an easy expression of the experience of aplain man whose life has never been worried by any philosopher higher than that of the shepherd in As You Like It. 但是,我的信息是一部作品,一条朝圣之路,一个普通人的经验的简单表述——他的生活从未因为任何比《皆大欢喜》里那个牧羊人高明的哲学家而担忧过。

I wish to point out a path in which the wayfaring man, though a fool, cannot err; 我希望指出一条道路,即使一个愚笨的旅人也不会走错;not a system to be worked out painfully only to be discarded, not a formal scheme, simply a habit as easy – or as hard! – to adopt as any other habit, good or bad.它不是一个需要苦心经营,却终为人所抛弃的制度,不是一个一个正式的规划,而只是一个习惯,如同其他或好或坏的习惯一样地容易养成——或者一样不容易养成。

A few years ago a Xmas card went the rounds, with the legend,几年前有一种圣诞贺卡十分流行,上面写道,"Life is just one 'denied' thing after another," 生活就是一个接一个的“拒签”which, in more refined language, is the same as saying,用更精炼的语言说,就等于是"Life is a habit,"“生活是一种习惯”a succession of actions that become more or less automatic. 是一系列或多或少地无意识的行为。

This great truth, which lies at the basis of all actions,这一伟大的真理存在于一切生理和心理行为的基础之中muscular or psychic, is the keystone to the teaching of Aristotle,是亚里士多德的教育之要旨,to whom the formation of habits was the basis of moral excellence.对他来说,习惯的养成乃是道德优越之本。

"In a word, habits of any kind are the result of actions of the same kind; and so what we have to do, is to give a certain character to these particular actions" (Ethics). “”简而言之,任何习惯都是同一种行为的结果;因而我们要做的,就是赋予这些特定行为某种特性。

”(《伦理学》)Lift a seven month-old baby to his feet –see him tumble to his nose. 把一个七个月的婴儿举起来让他双脚站立--他会摔个大头朝地。

Do the same at twelve months –he walks. 同样对一个十二个月的孩子--他能走路了。

At two years he runs. 两岁他就会跑了。

The muscles and the nervous system have acquired the habit. 肌肉和神经系统已经获得了那种习惯。

One trial after another, one failure after another, has given him power. 一次接一次的尝试,一个又一个的失败,这些都赋予他力量。

Put your finger in a baby's mouth, and he sucks away in blissful anticipation of a response to a mammalian habit millions of years old. 把你的手指放进一个婴儿的嘴里,他会带着愉悦的期待,盼望着得到一个百万年孕育出的母性习惯的回应。

And we can deliberately train parts of our body to perform complicated actions with unerring accuracy. 而且我们可以有意地训练我们的部分身体分毫不差地执行复杂的动作。

Watch that musician playing a difficult piece. 看那音乐家演奏一首有难度的作品。