EAU泌尿系结石诊疗指南

- 格式:pptx

- 大小:1.22 MB

- 文档页数:32

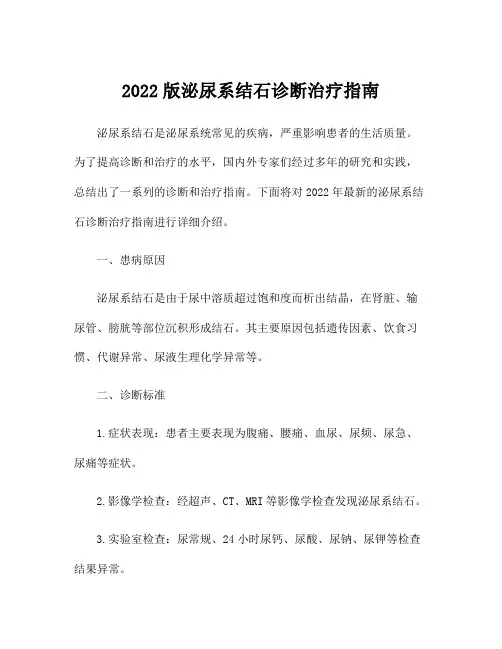

2022版泌尿系结石诊断治疗指南泌尿系结石是泌尿系统常见的疾病,严重影响患者的生活质量。

为了提高诊断和治疗的水平,国内外专家们经过多年的研究和实践,总结出了一系列的诊断和治疗指南。

下面将对2022年最新的泌尿系结石诊断治疗指南进行详细介绍。

一、患病原因

泌尿系结石是由于尿中溶质超过饱和度而析出结晶,在肾脏、输尿管、膀胱等部位沉积形成结石。

其主要原因包括遗传因素、饮食习惯、代谢异常、尿液生理化学异常等。

二、诊断标准

1.症状表现:患者主要表现为腹痛、腰痛、血尿、尿频、尿急、尿痛等症状。

2.影像学检查:经超声、CT、MRI等影像学检查发现泌尿系结石。

3.实验室检查:尿常规、24小时尿钙、尿酸、尿钠、尿钾等检查结果异常。

三、治疗方案

1.非手术治疗:对于直径小于5mm的肾结石,可以采取饮水、利尿剂、体位调整等非手术治疗方法,促进结石排出。

2.冲击波碎石术:对于直径大于5mm的结石,尤其是在输尿管内的结石,可以采用非创伤性冲击波碎石术进行治疗。

3.内镜取石术:对于输尿管内结石无法通过药物或冲击波碎石术排出的患者,可以采用内镜取石术进行治疗。

四、预防措施

1.饮食调整:限制高盐、高蛋白饮食,减少食用含草酸盐食物。

2.多饮水:每天饮水量不少于2000ml,促进尿液稀释。

3.药物治疗:如尿酸结石可口服碱化尿液的药物,钙结石可口服降钙药物。

以上就是2022版泌尿系结石诊断治疗指南的详细介绍,希望可以为临床医生和患者提供参考,提高泌尿系结石的治疗水平。

2012EAU 男性LUTS 指南1.简介老年人的下尿路症状通常是由于增大的前列腺造成的。

其产生机制是以下几点中的一点或全部:组织学的良性前列腺增生(BPH)、良性前列腺肥大(BPE)和良性前列腺梗阻(BPO)。

然而,最近几十年中前列腺与下尿路症状的病因学是否有关存在争议,尽管在一部分40岁以上的男性患者中增大的前列腺会导致下尿路症状,其他的一些原因也具有同等的重要性。

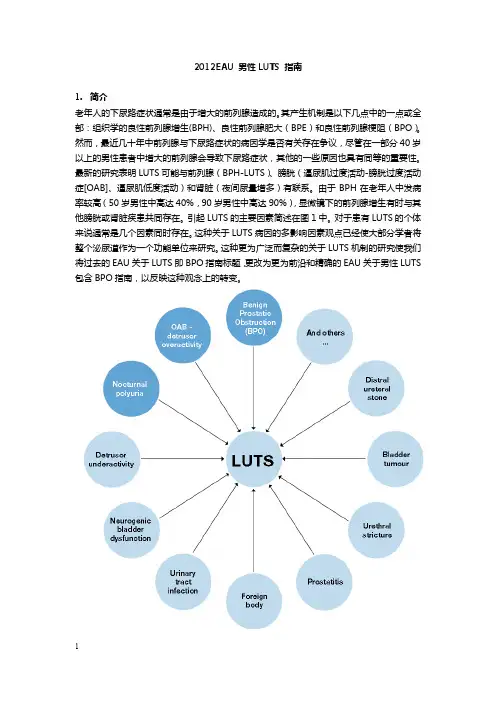

最新的研究表明LUTS可能与前列腺(BPH-LUTS)、膀胱(逼尿肌过度活动-膀胱过度活动症[OAB]、逼尿肌低度活动)和肾脏(夜间尿量增多)有联系。

由于BPH在老年人中发病率较高(50岁男性中高达40%,90岁男性中高达90%),显微镜下的前列腺增生有时与其他膀胱或肾脏疾患共同存在。

引起LUTS的主要因素简述在图1中。

对于患有LUTS的个体来说通常是几个因素同时存在。

这种关于LUTS病因的多影响因素观点已经使大部分学者将整个泌尿道作为一个功能单位来研究。

这种更为广泛而复杂的关于LUTS机制的研究使我们将过去的EAU关于LUTS即BPO指南标题,更改为更为前沿和精确的EAU关于男性LUTS 包含BPO指南,以反映这种观念上的转变。

由于病人因LUTS而来访并非是由于潜在的前列腺疾病,比如BPH或BPE,这次更新的指南来源于病人主诉各种各样的膀胱储尿期、排尿期和或排尿后后症状。

指南中更改的建议是基于最佳的可得证据。

这些更改建议适用于年龄40岁或以上的因各种非神经源性的良性LUTS疾患而来专科就诊的男性患者,比如LUTS/BPO、逼尿肌过度活动-OAB、夜尿症。

关于神经源性的LUTS的诊断与治疗在其他地方论述,适用于由于神经源性疾病而导致膀胱症状的男性或女性患者。

EAU指南关于尿失禁、泌尿系感染、泌尿系结石或恶性病变导致的LUTS在其他地方论述。

指南的修订意见是基于1966年到2010年1月发表在PubMed/Medline、Web of Science和Cochrane数据库的英文文献的系统性文献检索。

EAU《指南》要点解读:特殊肾结石的管理一、残留结石的管理残留肾结石的临床问题与发展的风险有关:·新结石(非均质成核);·持续的UTI;·碎石片移动引起有/无阻塞症状及其它症状。

建议LE GR1b A识别相关生化危险因素,为结石患者或结石残余碎片患者提供适当的预防措施[178,325,326]。

4 C随访结石患者或结石残余碎片患者,需定期监测疾病进展。

感染性结石治疗后残留碎片的复发风险高于其他结石。

不管何种结石成分,5年内有21-59%的残留结石患者需要治疗。

结石碎片> 5 mm的结石与比其小的碎片更需要干预[178,324,327]。

有证据表明碎片> 2 mm结石更有可能生长,尽管这与一年内随访的再次干预率增加不相关。

治疗积极清除残留结石的指征和程序的选择与结石的治疗标准相同,包括重复的SWL 。

如果不需要干预,根据结石分析,患者风险组和代谢评估可能有助于防止结石残留片段的再生长。

证据摘要LE1b对于下盏的残留结石,可以同时进行倒转治疗,在强利尿下+机械振机动可能促进结石清除[270]。

建议LE GR1a A经冲击波碎石术和输尿管镜检查后,在存在残留碎片的情况下,使用α阻滞剂提供药物排石治疗可以改善碎片清除率。

表:处理残留结石碎片的建议残片(最大有症状残留结无症状残留结LE GR直径)石石< 4-5 mm去石定期随访(依4 C赖于风险因素)> 5 mm去石 4 C二、怀孕期间尿结石治疗及相关问题怀孕的尿路结石患者的临床管理很复杂,需要病人,放射科医师,产科医师和泌尿科医师密切协作。

如果无自发排石,或者如果发生并发症(例如诱导早产),需要放置输尿管支架或经皮肾造瘘,遗憾的是,通常孕妇对这些临时治疗有较差的耐受性相关,并且在怀孕期间,由于潜在的结石迅速生长,还需要多次更换输尿管支架这样的干预。

因此输尿管镜已成这些情况的合理的替代方案。

虽然可行,但在怀孕期间,逆行内窥镜和经皮去除肾结石,仍然虽患者自我决定,且只能在有经验的中心进行。

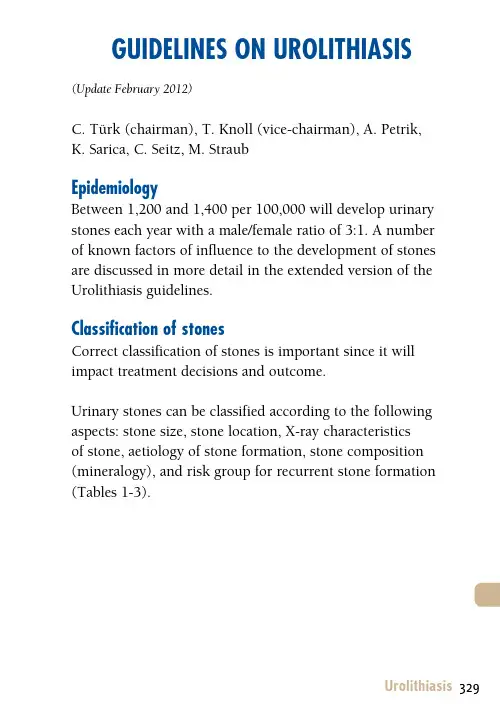

GUIDELINES ON UROLITHIASIS (Update February 2012)C. Türk (chairman), T. Knoll (vice-chairman), A. Petrik, K. Sarica, C. Seitz, M. StraubEpidemiologyBetween 1,200 and 1,400 per 100,000 will develop urinary stones each year with a male/female ratio of 3:1. A number of known factors of influence to the development of stones are discussed in more detail in the extended version of the Urolithiasis guidelines.Classification of stonesCorrect classification of stones is important since it will impact treatment decisions and outcome.Urinary stones can be classified according to the following aspects: stone size, stone location, X-ray characteristicsof stone, aetiology of stone formation, stone composition (mineralogy), and risk group for recurrent stone formation (Tables 1-3).Risk groups for stone formationThe risk status of a stone former is of particular interest as it defines both probability of recurrence or (re)growth of stones and is imperative for pharmacological treatment.DIAGNOSISDiagnostic imagingStandard evaluation of a patient includes taking a detailed medical history and physical examination. The clinical diag-nosis should be supported by an appropriate imaging proce-dure.*Upgraded following panel consensus.If available, ultrasonography, should be used as the pri-mary diagnostic imaging tool although pain relief, or any other emergency measures should not be delayed by imag-ing assessments. KUB should not be performed if NCCT is considered; however, it is helpful in differentiating between radiolucent and radiopaque stones and for comparison dur-ing follow-up.Evaluation of patients with acute flank painNon-contrast enhanced computed tomography (NCCT) has become the standard for diagnosis of acute flank pain since it has higher sensitivity and specificity than IVU.Indinavir stones are the only stones not detectable on NCCT.Biochemical work-upEach emergency patient with urolithiasis needs a succinct biochemical work-up of urine and blood besides the imaging studies. At that point no difference is made between high- and low-risk patients.Examination of sodium, potassium, CRP, and blood coagula-tion time can be omitted in the non-emergency stone patient.Patients at high risk for stone recurrences should undergo a more specific analytical programme (see section MET below).Analysis of stone composition should be performed in all first-time stone formers (GR: A). It should be repeated in case of:• Recurrence under pharmacological prevention• Early recurrence after interventional therapy with com-plete stone clearance• Late recurrence after a prolonged stone-free period (GR: B)The preferred analytical procedures are:• X-ray diffraction (XRD)• Infrared spectroscopy (IRS)Wet chemistry is generally deemed to be obsolete. Acute treatment of a patient with renal colicPain relief is the first therapeutic step in patients with an acute stone episode.inflammatory drug.*Caution: Diclofenac sodium affects GFR in patients with reduced renal function, but not in patients with normal renal function (LE: 2a). ** (see extended document section 5.3)If pain relief cannot be achieved by medical means, drain-age, using stenting or percutaneous nephrostomy, or stone removal, should be carried out.Management of sepsis in the obstructed kidneyThe obstructed, infected kidney is a urological emergency.In exceptional cases, with severe sepsis and/or the formation of abscesses, an emergency nephrectomy may become neces-sary.Stone reliefWhen deciding between active stone removal and conserva-tive treatment using MET, it is important to consider all the individual circumstances of a patient that may affect treat-ment decisions.Observation of kidney stonesIt is still debatable whether kidney stones should be treated, or whether annual follow-up is sufficient for asymptomatic caliceal stones that have remained stable for 6 months.Medical expulsive therapy (MET)For patients with ureteral stones that are expected to pass spontaneously, NSAID tablets or suppositories (i.e. diclofenac sodium, 100-150 mg/day, over 3-10 days) may help to reduce inflammation and the risk of recurrent pain.Alpha-blocking agents, given on a daily basis, reduce recur-rent colic (LE: 1a). Tamsulosin, has been the most com-monly used alpha blocker in studies.Chemolytic dissolution of stonesOral or percutaneous irrigation chemolysis of stones can be a useful first-line therapy or an adjunct to SWL, PNL, URS, or open surgery to support elimination of residual fragments. However, its use as first-line therapy may take weeks to be effective.Percutaneous irrigation chemolysis* Alternatively, one nephrostomy catheter with a JJ stent and bladder catheter can serve as a through-flow system preventing high pressure.Methods of percutaneous irrigation chemolysisOral ChemolysisOral chemolitholysis is efficient for uric acid calculi only. The urine pH should be adjusted to between 7.0 and 7.2.SWLThe success rate for SWL will depend on the efficacy of the lithotripter and on:• size, location (ureteral, pelvic or calyceal), and composi-tion (hardness) of the stones;• patient’s habitus;• performance of SWL.Contraindications of SWLContraindications to the use of SWL are few, but include:• pregnancy;• bleeding diatheses;• uncontrolled urinary tract infections;• severe skeletal malformations and severe obesity, which prevent targeting of the stone;• arterial aneurism in the vicinity of the stone;• anatomical obstruction distal of the stone.Stenting prior to SWLKidney stonesA JJ stent reduces the risk of renal colic and obstruction, but does not reduce formation of steinstrasse or infective compli-cations.Best clinical practice (best performance)PacemakerPatients with a pacemaker can be treated with SWL, provided that appropriate technical precautions are taken; patients with implanted cardioverter defibrillators must be managed with special care (firing mode temporarily reprogrammed during SWL treatment). However, this might not be neces-sary with new-generation lithotripters.Number of shock waves, energy setting and repeat treat-ment sessions• The number of shock waves that can be delivered at each session depends on the type of lithotripter and shockwave power.• Starting SWL on a lower enegy setting with step-wise power (and SWL sequence) ramping prevents renalinjury.• Clinical experience has shown that repeat sessions are feasible (within 1 day for ureteral stones).Procedural controlResults of treatment are operator dependent. Careful imaging control of localisation will contribute to outcome quality. Pain controlCareful control of pain during treatment is necessary to limit pain-induced movements and excessive respiratory excur-sions.Antibiotic prophylaxisNo standard prophylaxis prior to SWL is recommended.Medical expulsive therapy (MET) after SWLMET after SWL for ureteral or renal stones can expedite expulsion and increase stone-free rates, as well as reduce additional analgesic requirements.Percutaneous nephrolitholapaxy (PNL)Best clinical practiceContraindications:• all contraindications for general anaesthesia apply;• untreated UTI;• atypical bowel interposition;• tumour in the presumptive access tract area;• potential malignant kidney tumour;pregnancy.•rograde transurethral manipulation, and easier anaesthesia. Disadvantages are limited manoeuvrability of instruments and the need of appropriate equipment.Ureterorenoscopy (URS)(including retrograde access to renal collecting system) Best clinical practice in URSBefore the procedure, the following information should be sought and actions taken (LE: 4):• Patient history;• physical examination (i.e. to detect anatomical and con-genital abnormalities);• thrombocyte aggregation inhibitors/anticoagulation (anti-platelet drugs) treatment should be discontinued.However, URS can be performed in patients with bleeding disorders, with only a moderate increase in complications;imaging.•ContraindicationsApart from general considerations, e.g. with general anaes-thesia, URS can be performed in all patients without any spe-cific contraindications.Access to the upper urinary tractMost interventions are performed under general anaesthesia, although local or spinal anaesthesia are possible. Intravenous sedation is possible for distal stones, especially in women. Antegrade URS is an option for large, impacted proximal ureteral calculi.Safety aspectsFluoroscopic equipment must be available in the operating room. If ureteral access is not possible, the insertion of a JJ stent followed by URS after a delay of 7-14 days offers an appropriate alternative to dilatation.Ureteral access sheathsHydrophilic-coated ureteral access sheaths (UAS), can be inserted via a guide wire, with the tip placed in the proximal ureter. Ureteral access sheaths allow easy multiple access to the upper urinary tract and therefore significantly facilitate URS. The use of UAS improves vision by establishing a con-tinuous outflow, decrease intrarenal pressure and potentially reduce operating time.Stone extractionThe aim of endourological intervention is complete stone removal (especially in ureteric stones). ‘Smash and go’ strate-gies might have a higher risk of stone regrowth and post-operative complications.Stenting before and after URSPre-stenting facilitates ureteroscopic management of stones, improves the stone-free rate, and reduces complications. Following URS, stents should be inserted in patients who are at increased risk of complications.Open surgeryMost stones should be approached primarily with PNL, URS, SWL, or a combination of these techniques. Open surgery may be a valid primary treatment option in selected cases. Indications for open surgery:• Complex stone burden• Treatment failure of SWL and/or PNL, or URS• Intrarenal anatomical abnormalities: infundibular steno-sis, stone in the calyceal diverticulum (particularly in an anterior calyx), obstruction of the ureteropelvic junction, stricture if endourologic procedures have failed or are not promising• Morbid obesity• Skeletal deformity, contractures and fixed deformities of hips and legs• Comorbidity• Concomitant open surgery• Non-functioning lower pole (partial nephrectomy), non-functioning kidney (nephrectomy)• Patient choice following failed minimally invasive proce-dures; the patient may prefer a single procedure and avoid the risk of needing more than one PNL procedure• Stone in an ectopic kidney where percutaneous access and SWL may be difficult or impossible• For the paediatric population, the same considerations apply as for adults.Laparoscopic surgeryLaparoscopic urological surgery is increasingly replacing open surgery.Indications for laparoscopic kidney-stone surgery include:• complex stone burden;• failed previous SWL and/or endourological procedures;• anatomical abnormalities;• morbid obesity;• nephrectomy in case of non-functioning kidney. Indications for laparoscopic ureteral stone surgery include:• large, impacted stones;• multiple ureteral stones;• in cases of concurrent conditions requiring surgery;• when other non-invasive or low-invasive procedures have failed.If indicated, for upper ureteral calculi, laparoscopic uro-lithomy has the highest stone-free rate compared to URS and SWL (LE: 1a).Laparoscopic ureterolithotomy should be considered when other non-invasive or low-invasive procedures have failed.Indication for active stone removal and selection of procedureUreter:• stones with a low likelihood of spontaneous passage;• persistent pain despite adequate pain medication;• persistent obstruction;• renal insufficiency (renal failure, bilateral obstruction, sin-gle kidney).Kidney:• stone growth;• stones in high-risk patients for stone formation;• obstruction caused by stones;• infection;• symptomatic stones (e.g. pain, haematuria);• stones > 15 mm;• stones < 15 mm if observation is not the option of choice;• patient preference (medical and social situation);• > 2-3 years persistent stones.The suspected stone composition might influence the choice of treatment modality.STONE REMOVALRadiolucent uric acid stones, but not sodium urate or ammonium urate stones, can be dissolved by oral chemolysis. Determination is done by urinary pH.Selection of procedure for active removal of renal stones Figure 1: T reatment algorithm for renal calculi within the renal pelvis or upper and middle calicesKidney stone in renal pelvis orupper/middle calyx* F lexible URS is used less as first-line therapy for renal stones > 1.5 cm.** T he ranking of the recommendations reflects a panel majority vote.*** see Table 19 extended documentFigure 2: T reatment algorithm for renal calculi in the infe-rior calyxSelection of procedure for active stone removal of ure-teral stones (GR: A*)*Upgraded following panel consensus.Kidney stone in lower pole1. Endourology (PNL, flex. URS*)2. SWL1. SWL2. Flex. URS3. PNLSteinstrasseSteinstrasse occurs in 4% to 7% of cases after SWL, the major factor in steinstrasse formation is stone size.Residual stonesThe indication for active stone removal and selection of the procedure is based on the same criteria as for primary stone treatment and also includes repeat SWL.Management of urinary stones and related problemsduring pregnancyManagement of stone problems in children Spontaneous passage of a stone and of fragments after SWL is more likely to occur in children than in adults (LE: 4). For paediatric patients, the indications for SWL and PNL are similar to those in adults, however they pass fragments more easily. Children with renal stones with a diameter up to 20 mm (~300 mm2) are ideal candidates for SWL.*Upgraded from B following panel consensus.Stones in exceptional situationsGeneral considerations for recurrence prevention (all stone patients)• Drinking advice (2.5 – 3L/day, neutral pH);• Balanced diet;• Lifestyle advice.High-risk patients: stone-specific metabolic work-up and pharmacological recurrence prevention Pharmacological stone prevention is based on a reliable stone analysis and the laboratory analysis of blood and urine including two consecutive 24-hour urine samples. Pharmacological treatment of calcium oxalate stones (Hyperparathyreoidism excluded by blood examination)Pharmacological treatment of calcium phosphate stonesHyperparathyroidismElevated levels of ionized calcium in serum (or total calcium and albumin) require assessment of intact parathyroid hor-mone (PTH) to confirm or exclude suspected hyperparathy-roidism (HPT). Primary HTP can only be cured by surgery.Pharmacological treatment of uric acid and ammonium urate stonesStruvite and infection stonesPharmacological treatment of cystine stones2,8-dihydroyadenine stones and xanthine stonesBoth stone types are rare. In principle, diagnosis and specific prevention is similar to that of uric acid stones. Investigating a patient with stones of unknown compo-sitionThis short booklet text is based on the more comprehensive EAU guide-lines (ISBN 978-90-79754-83-0) available to all members of the European Association of Urology at their website, .。

泌尿系结石诊疗指南前言尿石症是泌尿外科的常见病,患病率高达5—10%,在我国尿石症患者占泌尿外科住院病人的近四分之一,严重影响了人们的身体健康。

近年来我国泌尿外科发展迅速,结石的各种治疗方法基本上已与国际接轨,但治疗方法的选择尚未进行规范化,导致部分医院在治疗方法的选择上随心所欲,或者根据其医疗条件选择治疗方法的问题。

为了规范结石的治疗,我们将2005年欧洲泌尿外科年会公布的泌尿系结石诊疗指南进行了编译和整理,希望对我国的尿石症治疗的规范化有所帮助。

中华泌尿外科学会泌尿系结石学组二OO五年十月目录1简介 (1)2结石患者分类 (1)3结石形成的危险因素 (2)4诊断 (2)4.1影像学诊断 (2)4.2实验室检查 (3)5治疗 (5)5.1缓解疼痛 (5)5.2取石 (6)5.2.1术前评估 (6)5.2.2治疗方法选择 (6)5.2.3输尿管结石的治疗原则 (7)5.2.4肾结石取石的基本原则 (9)5.3钙结石的预防措施…………………………………(10)5.4钙结石的药物治疗 (11)5.5尿酸结石的药物治疗 (12)5.6胱氨酸结石的药物治疗 (12)5.7感染性结石的药物治疗 (13)6总结 (13)1.简介泌尿系结石在临床上一直占有重要地位。

一个人一生患结石的风险在5—10%之间。

男性发病率高于女性,两者比率约为3:1,发病高峰年龄为40-50岁。

任何类型结石都有可能复发,而且在临床上复发性结石多见,是治疗和预防的重点。

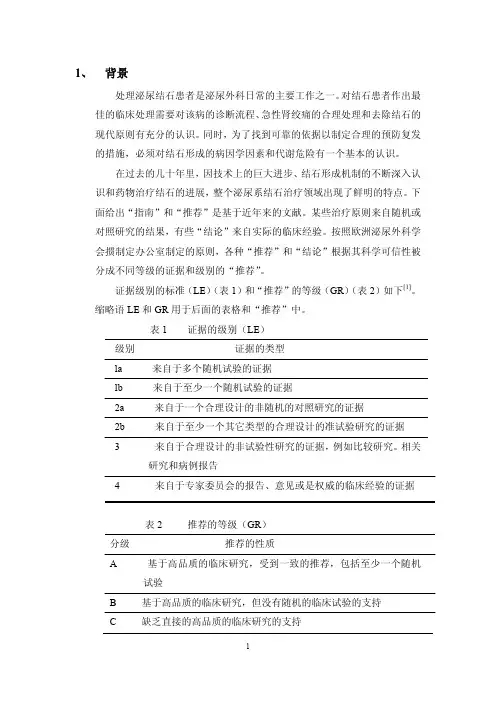

2.结石患者分类基于结石的化学组成和疾病的严重程度,我们可以将结石患者分为不同类型(见表1)。

表1:结石患者分类描述缩写感染性结石 INF 非钙结石尿酸/尿酸钠/尿UR 胱氨酸结石 CY 发结石患者,无残余结石S 0初发结石患者,有残余结石 S res 钙结石复发结石患者,病情轻度,无残余结石S m-0复发结石患者,病情轻度,有残余结石S m-res复发结石患者,病情重度,有或无残余结R s有特殊危险因素的结石患者,不考虑其他已定义类别 Risk 3.结石形成的危险因素由于一些特殊危险因素的存在,部分患者需要特别引起注意(见表2)。

EAU《指南》要点解读:输尿管软镜(RIRS )2024技术改进包括内窥镜小型化,改进偏转机制,增强光学质量具,以及一次性用品的引入导致了肾脏和输尿管结石对软镜的更多使用。

RIRS已取得重大技术进步。

最近SR针对肾脏结石>2厘米研究,显示累积SFR为91% ,每位患者手术次数为1.45;并发症≥Clavien 分级3为4.5%o 由于图像的改进,更好的图像质量及数字化示波器,使得术者减少了操作时间。

不能直接取出的结石,必须粉碎。

如果难以对肾下极结石进行碎石,可用取石装置将结石移至方便碎石的肾rm o除了一般性情况,例如,全麻的问题或未经治疗的UTI问题,总的来说RIRS并无特别的禁忌症。

(—)麻醉大多数干预措施是在全身麻醉下进行的,尽管也可在局部麻醉或脊髓麻醉下完成。

静脉镇静用药可用于女性输尿管结石的患者。

(二)安全X光检查设备必须可在手术室中应用。

我们建议放置安全导丝,即使一些研究也已证明,RIRS也可以在没有安全导丝下进行。

如有必要,应提供气囊或其它扩张器。

在软镜应用之前,可先用刚性输尿管镜,起到扩张作用,随后用软镜。

此外,如果不能进入输尿管通路,可先期通过输尿管镜放双J支架7到14天,作为替代程序。

一期可以同时解决两侧输尿管结石,有相类似的SFR ,但并发症发生率稍微增高(大部分并发症是次要的)0 (Ξ )输尿管通道鞘亲水涂层的输尿管通道鞘,可有不同的直径(内径从9 F向上),可以通过导丝插入,其末端放置在输尿管近端。

输尿管通道鞘允许较为容易,多次进入上尿路,因此大大方便了URS o输尿管通道鞘的使用可提高手术视野的清晰度,这是因为液体可持续通畅的流出,减少肾内压力,并有利于减少手术时间。

输尿管通路鞘的插入可能导致输尿管损伤,但术前放置支架风险降低。

没有关于输尿管通路鞘应用后长期副作用的数据。

另外是否使用输尿管通道鞘还取决于外科医生的偏好。

(四)取石RlRS的目标是完全去除结石。

"粉未化与去石”战略对较大的(肾)结石来说并不合适。

泌尿系结石诊疗指南治疗(一) 肾绞痛的治疗1.药物治疗(1)非甾体类镇痛抗炎药物:双氯芬酸钠50mg,肌肉注射。

消炎痛为25mg,口服,或者消炎痛栓剂100mg,肛塞。

(2)阿片类镇痛药:二氢吗啡酮(5~10mg,肌肉注射)、哌替啶(50~100mg,肌肉注射)、强痛定(50~100rng,肌肉注射)和曲马朵(100mg,肌肉注射)等。

阿片类药物在治疗肾绞痛时不应单独使用,一般需要配合阿托品、654-2等解痉类药物一起使用。

北京积水潭医院泌尿外科李贵忠(3)解痉药:①M型胆碱受体阻断剂,常用药物有硫酸阿托品和654-2,20mg,肌肉注射;②黄体酮③钙离子阻滞剂,硝苯地平10mg口服或舌下含化;④α-受体阻滞剂(坦索罗辛)。

对首次发作的肾绞痛治疗应该从非甾体抗炎药开始,如果疼痛持续,可换用其他药物。

吗啡和其他阿片类药物应该与阿托品等解痉药一起联合使用。

此外,针灸刺激肾俞、京门、三阴交或阿是穴也有解痉止痛的效果。

2.外科治疗当疼痛不能被药物缓解或结石直径大于6mm时,应考虑采取外科治疗措施。

其中包括:(1)体外冲击波碎石治疗(extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy,ESWL),将ESWL作急症处置的措施,通过碎石不但能控制肾绞痛,而且还可以迅速解除梗阻。

(2)输尿管内放置支架,还可以配合ESWL治疗。

(3)经输尿管镜碎石取石术。

(4)经皮肾造瘘引流术,特别适用于结石梗阻合并严重感染的肾绞痛病例。

治疗过程中注意有无合并感染,有无双侧梗阻或孤立肾梗阻造成的少尿,如果出现这些情况需要积极的外科治疗,以尽快解除梗阻。

(二) 排石治疗临床上绝大多数尿路结石可以通过微创的治疗方法将结石粉碎并排出体外,只有少数比较小的尿路结石可以选择药物排石。

1.排石治疗的适应证(1)结石直径小于0.6cm。

(2)结石表面光滑。

(3)结石以下尿路无梗阻。

(4)结石未引起尿路完全梗阻,停留于局部少于2周。